Law & Order's prime-time formula shaped a generation's understanding of the legal system

Photo illustration by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock

NARRATOR (V.O.)

In the criminal justice system, the people are represented by two separate yet equally important groups: The police, who investigate crime, and the district attorneys, who prosecute the offenders. These are their stories.

Two loud CLANGS, which evoke the slamming of a prison cell combined with the bang of a judge’s gavel.

TEASER

FADE IN

EXT. PARKING LOT ON THE UPPER EAST SIDE - DAY

Two men dressed in matching work uniforms are walking around the lot, picking up trash and making small talk.

MAN 1

Hey, did you see the game last night?

MAN 2

Oh yeah, it was horrible. Man, the Mets suck. Rogers couldn’t throw it past my grandma right now. (notices MAN 1 has gone silent) What’s wrong?

MAN 1(standing near dead body)

Oh my God! Call the police!

The detectives arrive and do a quick canvass of the crime scene before one of them employs some gallows humor and cracks a one-liner (in this case, since they’re in a parking lot, maybe something about a spot opening up or a parking meter expiring) as the screen fades and the opening credits run.

During the course of the one-hour episode, which often involves a fictitious portrayal of a real-life high-profile criminal case, the police spend the first half-hour pursuing leads, interviewing suspects and eventually arresting someone before the assistant district attorneys take over in the second 30 minutes. Sometimes the prosecutors win; other times, they lose. Oftentimes, they make a plea bargain. The following week, it’s the same thing, only with a new victim, defendant and crime.

When it comes to formulas, arguably only Coca-Cola’s has been more successful. During its original broadcast run from 1990 until 2010, Law & Order became a cultural phenomenon. It won multiple awards, including the Emmy for best drama series in 1997, and it was a top-10 show at its peak of popularity in the early 2000s. With an emphasis on procedure as the primary plot device and less reliance on exploring characters’ personal lives or relationships, the success of the show spawned numerous similar shows and spin-offs while inspiring countless fans to go to law school or pursue careers in law enforcement.

Mariska Hargitay as SVU’s Lt. Olivia Benson. Photo by: David Giesbrecht/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images via Getty Images

Even though the show ended more than a decade ago, episodes are regularly aired in syndication. Meanwhile, spin-off Law & Order: Special Victims Unit is still in production with a run that has surpassed that of the original series. In fact, Law & Order franchise creator Dick Wolf has spawned his own universe, taking up two entire nights of prime-time programming on NBC with Chicago Wednesdays (Chicago P.D., Chicago Med and Chicago Fire), and starting in the fall, Law & Order Thursdays (SVU, Law & Order: Organized Crime and the debuting Law & Order: For the Defense, a new series announced in May that will focus on a criminal defense firm). Wolf declined to be interviewed for this piece.

“It was a tremendously innovative show in that it concentrated on the case and police catching the bad guy and the prosecutor putting them away,” says Michael Asimow, professor of law emeritus at UCLA School of Law and co-author of Law and Popular Culture: A Coursebook. “How is it that viewers would continue to watch a show like this with no sex, no violence, no character development? Just the power of people doing their jobs. But that formula worked.”

Jessica Silbey, a professor of intellectual property and constitutional law at Boston University School of Law and Asimow’s co-author, says the show reinforces what Americans love and find unique about their criminal justice system. “I think the American obsession with law as a cultural identity makes shows like Law & Order attractive,” she says. “They highlight a part of the American identity that Americans feel very proud of.”

The franchise’s success earned creator Dick Wolf a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2007. Photo by M. Tran/FilmMagic

However, critics argue that the show has presented a highly idealized picture of law enforcement and the criminal justice system to viewers that makes it difficult to convince the general public that meaningful reforms are needed. Perhaps it’s fitting that, in this era of Black Lives Matter and heightened tensions between police and minority communities, not even the long-resilient Law & Order universe has been immune.

From hamburger to hero

Ironically, Law & Order debuted at a time when the courtroom drama was at its nadir. According to Elayne Rapping’s 2003 book, Law and Justice as Seen on TV, there were exceptions, notably Matlock, the spiritual successor to Perry Mason starring well-known TV actor Andy Griffith, and Steven Bochco’s L.A. Law, a “ripped-from-the-headlines” show that focused on current events but from the vantage point of a glitzy corporate firm with attractive lawyers whose personal lives were an integral part of the show. But the focus in the ’80s was very much on cops, be they good ones such as on Cagney & Lacey or more morally ambiguous ones such as those on Hill Street Blues or Miami Vice.

By the 1990s, interest in courtroom procedure was on the upswing, thanks to the rise of Court TV. Law & Order, which debuted on Sept. 13, 1990, on NBC as an ensemble drama with mostly lesser-known actors, might not have been the betting choice to become a success. (The Trials of Rosie O’Neill, focusing on public defenders and starring Sharon Gless, premiered on CBS four days later. It lasted two seasons.) Originally consisting of five white males and one Black male, the show brought aboard a Black woman and a white woman for the fourth season in response to pressure from network executives.

Snoop Dogg guest-starring on SVU in 2019. Photo by James Devaney/GC Images

One thing that didn’t change? The show’s innovative structure and formula. According to the New York Times, this was done so the show could be easily split in two and aired in syndication, which favored half-hour shows at the time.

There were other features that made Law & Order distinctive. Michael Chernuchin, a producer and writer who worked on the show during the first season, says it had more in common with a show like Dragnet, which spawned the famous catchphrase: “Just the facts, ma’am.”

“It was a new way of telling a story, with lots of people talking a lot. On other shows, you have people emoting and whatnot, but this was just the facts,” Chernuchin says. He takes issue with the notion that there was no character development, however, noting that viewers learned plenty about characters by watching them do their jobs. “If you watch 10 episodes, then you end up knowing a lot about these people,” he says. “We believed in letting a character out with an eyedropper. That way, you build up great momentum, and it makes for exciting storytelling.”

The very fact that the show focused on prosecutors instead of defense attorneys was a major point of departure. As Asimow and Michael Epstein, a professor of law and director of the entertainment and media law concentration at Southwestern Law School point out, historically, crime dramas were in the Perry Mason mold, with crusading defense attorneys protecting innocent clients from prison. In fact, on Perry Mason, law enforcement was so incompetent—one of the main prosecutors was even named Hamilton Burger (as in “hamburger”) because “Mason made mincemeat out of him every week,” Epstein says—that the titular character had to act as both investigator and defense counsel.

“With Law & Order, it was the opposite,” Asimow says. “You had highly competent, ethical people usually putting away bad people—often against serious obstacles.” He adds that defense attorneys often come across less as crusading and more as obstructionist, possibly even unethical. “Defense attorneys are often there to throw up roadblocks through technicalities—even though that’s their job,” Asimow says. “That shifts the cultural emphasis by saying, ‘We should respect prosecutors, but not so much defense lawyers.’”

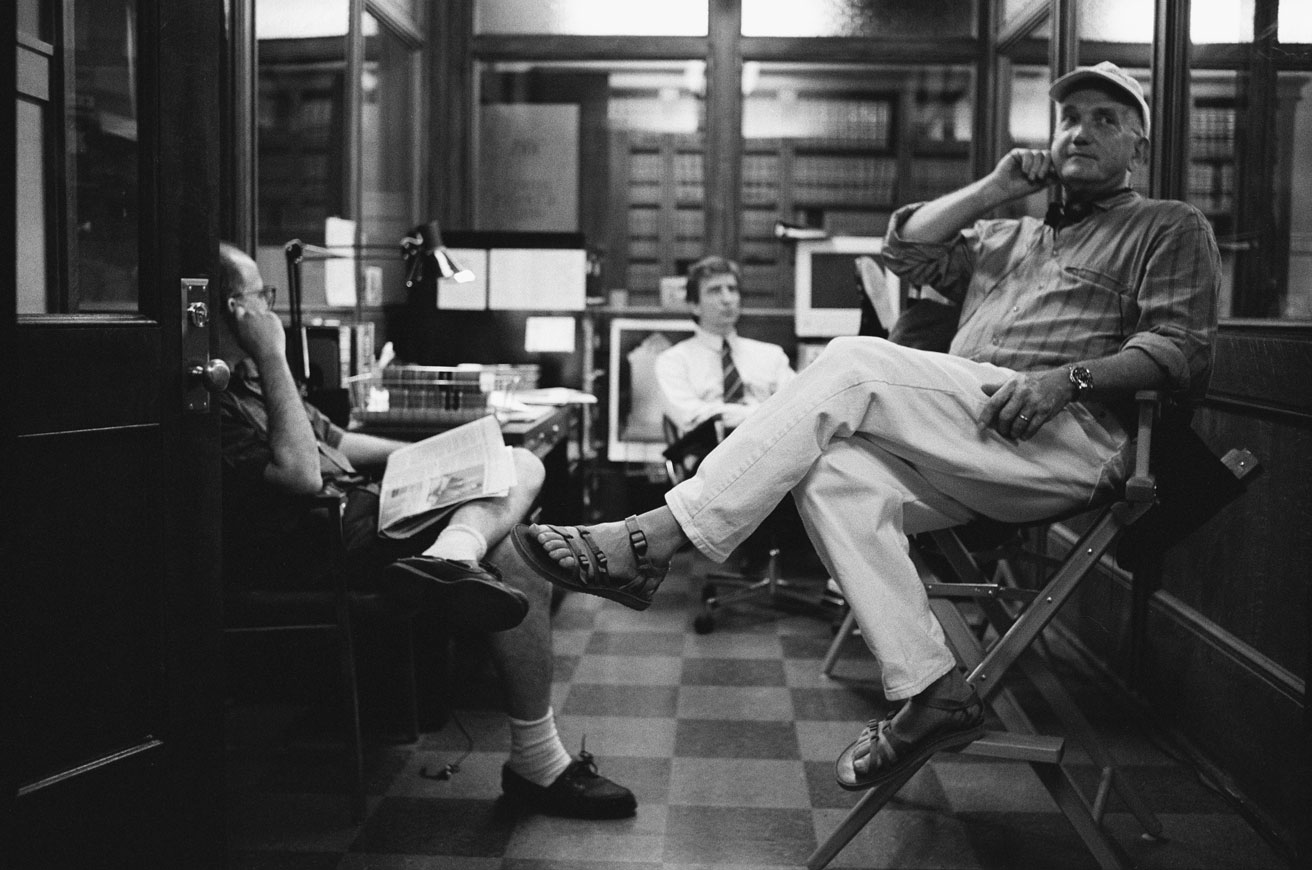

Sam Waterston (back-ground) and director Edwin Sherin (front) on the set of Law & Order. Photo by NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images via Getty Images

Indeed, Law & Order’s structure and storytelling formula make it inevitable that viewers would identify and sympathize with the police and prosecutors while being hostile toward defense attorneys.

“Even if they’re not on screen all of the time, the narrative formula requires defense attorneys to be a foil to the detectives and prosecutors,” Epstein says. “Oftentimes, the defense attorney is the one character, along with accused, that shows up in both halves of the episode. This is significant to the way the stories are told. Because if the defense attorney does his/her job well, they can stop the story from progressing towards trial.”

However, William Fordes, a former assistant district attorney with the Manhattan DA’s office who served as a producer, writer and consultant on Law & Order, maintains that the show tried to present a balanced view of the criminal justice system.

“One of the writers was from Legal Aid, so he protected that side of the story,” Fordes says. “We never set out to make anyone a hero. They all did what they thought was the right thing. Sometimes, they were wrong and made mistakes.” According to Fordes, the mantra at the show was “if you have an episode where half the audience thinks the defendant is innocent, half think he’s guilty, and the third half isn’t sure, then you’ve done your job.”

In fact, according to people who worked on the show, the emphasis on accuracy extended to caselaw, criminal procedure and constitutional law. “Dick [Wolf] always wanted us to be as accurate as possible when it came to courtroom scenes, but also in the use of cases,” says Fordes, who also served as co-executive producer for The Man in the High Castle and got his start as a legal consultant for the 1990 film Presumed Innocent. “Every case we ever cited on the show was accurate, and every explanation was precise.”

Both Chernuchin and Ed Zuckerman, a staff writer who wrote the script for the first episode that made it to air, referred to the New York Post, a newspaper famous (or infamous) for its sensational, tabloid-style, attention-grabbing headlines—often about some gruesome murder—as the show’s bible.

“We would take something from the New York Post so the audience would recognize it, but then go off in our own direction,” says Chernuchin, who earned a master’s in English from the University of Michigan and a JD from Cornell Law School and would go on to become showrunner—the main producer and person in charge—of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit in 2017. For instance, some famous episodes were based on actual cases or issues, including “Teenage Wasteland,” an episode based on the murder of a Chinese food deliveryman by five teenagers in Queens, and “Indifference,” which was based on the famous Lisa Steinberg child abuse case.

Chernuchin, who also served as a consulting producer on 24 and executive producer on Michael Hayes and Brooklyn South, among other shows, concedes they had to take a few liberties here and there, such as speeding up the trial so that it could fit into a half-hour of television. “But we never lied about the law,” says Chernuchin, who kept law books on his desk and tried to be as accurate as possible when citing jurisprudence or statutory law. “We used real law and didn’t let the staff do anything that wouldn’t happen in a real court of law.”

For Zuckerman, those law books served an additional purpose: story fodder. For instance, he recounts how one of his favorite episodes, a season 9 tale titled “Scrambled,” involved several unique points of law. The story, which was about a murder at a fertility clinic and a subsequent struggle over ownership of frozen embryos that turned on whether they counted as property or people, came about as a result of his research. The story was based on a real case (Kass v. Kass, a 1998 New York Court of Appeals decision), but Zuckerman added some fictionalized story elements and other real legal issues.

“Oftentimes, I’d look through the annotated penal law, and it has a lot of cases listed,” says Zuckerman, who had several stints as a writer and producer on Law & Order, Law & Order: SVU and Law & Order Criminal Intent, along with other shows such as JAG and Blue Bloods. “If you look through those cases, you’d often find one that had an interesting twist.”

Conversely, the devotion to accuracy may have raised expectations for people if they become involved with the real criminal justice system. Fordes notes how when he would give presentations to New York City lawyers, sometimes they would be upset that the lawyers on television were so eloquent and efficient with their arguments and questioning of witnesses.

“They would say, ‘If we stop and look at our notes for a few seconds, then the jury gets outraged because they think it should be like the show,’” Fordes recounts. “I would reply that if that was their main concern, then maybe they should try a new career.”

Linus Roache as Executive Assistant District Attorney Michael Cutter on Law & Order. Photo by: Virginia Sherwood/NBCU Photo Bank

Spin-off success

Like The Jeffersons, The Facts of Life, The Simpsons and a few other spin-offs, Law & Order: Special Victims Unit has managed to outlast its parent show. Focusing on sex crimes, SVU is very much a cop-centric show—there are entire episodes in which the ADA doesn’t make an on-camera appearance at all. While the original series is very much an ensemble show, SVU has a clear star (Mariska Hargitay as Capt. Olivia Benson) and the characters, on the whole, are more developed.

Chernuchin was serving as showrunner for Wolf’s Chicago Justice, a Law & Order-style show, when it was canceled after one season. He then became showrunner for SVU for two seasons starting in 2017.

“SVU emphasizes the victim more than the crime and the criminals,” he says, adding that the ability to do more character-driven storylines and plots appealed to him. “I think lots of people latched onto that. Empathy became a much bigger theme.”

The show has received acclaim for bringing awareness to sex crimes and survivors.

According to a 2015 study conducted by Stacey Hust, a professor of communications at Washington State University, and four others, people who watch SVU and other Law & Order shows understand sexual consent more than people who watch other crime shows.

Kristen Feden, a former prosecutor who convicted Bill Cosby on three counts of aggravated indecent assault in April 2018, adds that the show has been helpful in destigmatizing what it means to be a survivor of sexual assault or rape.

“The show stuck with the message that rape is not limited to poor people or promiscuous people, or to white, Black, rich or poor, it can happen to anyone,” says Feden, who is currently an associate with Saltz Mongeluzzi & Bendesky in Philadelphia. “If we look at it with a unified lens, we begin to see it’s a crime that we need to eliminate.”

In fact, she cites “Undercover,” a season 9 episode in which SVU’s Benson goes undercover at a prison and is nearly raped by a corrections officer who does not realize she is a cop, as one of her favorite episodes because it conveys that very message.

“Many people say: ‘It will never happen to me,’” Feden says. “But when you feel that way, it’s hard for you to empathize with people who have undergone that trauma.”

Ultimately, Feden credits the show with not just making people more aware of the breadth, complexity and scope of sex crimes, but also with promoting a basic sense of humanity and respect for survivors of sexual abuse and assault. And she says that was what drove her prosecution of Cosby for the assault of Andrea Constand.

First and foremost was treating Constand with courtesy and compassion, and that meant apologizing on behalf of her office for not prosecuting her case more than a decade ago.

“I wasn’t part of the decision not to prosecute Cosby [in 2005], but as a representative of the office, I felt like we did fail her,” Feden says. “So we took that opportunity to apologize to her.”

However, that decision resulted in a plot twist that could have easily been seen on an episode of SVU. In June, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court overturned Cosby’s conviction, ruling that the 2005 decision not to prosecute by the previous DA was binding on his successors.

Feden said that she and the trial court did not believe there was an agreement in place and respectfully disagreed with the supreme court.

“He was found to have sexually assaulted Andrea Constand,” Feden said in an interview on MSNBC. “Yes, he does not sit before you as a guilty man. He does, however, still sit before you as a sexual predator.”

Dick Wolf and crew celebrate the 300th episode of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit. Photo by: Will Hart/NBC

Law & Order versus ‘law and order’

For many, the Law & Order universe was their introduction not just to the criminal justice system, but also to matters relating to constitutional law and procedure. “I like to say that, before Law & Order, people knew there was a Constitution; afterwards, they knew there was a Bill of Rights,” Chernuchin says. “The show taught Americans about the criminal justice system.”

However, others argue the viewers inevitably learn about the system from the point of view of the show’s protagonists. “They definitely make prosecutors very sympathetic,” Silbey says. “They are presented as having a hard job to do. It facilitates us in thinking that prosecutors are generally admirable.”

Kristen Marston, culture and entertainment advocacy director at nonprofit civil rights advocacy group Color of Change, goes further by saying that shows like Law & Order only reinforce negative qualities endemic to the criminal justice system. In 2020, Color of Change released a report titled Normalizing Injustice that found shows such as Law & Order and SVU have glamorized law enforcement while creating false narratives or distorting the effect of the criminal justice system on minorities and women. The report found that over 80% of the writers on the 26 crime shows in production during the 2017-2018 season were white, while 21 of those programs had a white male as showrunner. This lack of diversity, according to Color of Change’s press release about the report, was the key reason why crime shows “build on false perceptions of the criminal justice system and how it intersects with race and gender while ignoring many important realities,” potentially making viewers hostile toward reforms.

“Tens of millions of people learn about the criminal justice system through procedural dramas that advance debunked ideas about crime from a false hero narrative that skews in favor of law enforcement and distorts representations about Black people, people of color and women,” Marston says. “These shows have rendered racism invisible and dismiss the need for police accountability.”

Marston argues that a long-running and successful show like Law & Order distorts the realities of the criminal justice system—a myopic view that inevitably influences how people perceive the actual criminal justice system.

“Decades of research has demonstrated that TV viewing can have profound effects on social attitudes, either reinforcing implicit social norms or helping redefine them,” she states. “Given the pervasive presence of crime series in American popular culture, it makes sense that the social, societal and professional norms depicted in them play a significant role in educating everyday Americans about both the criminal justice system and the many social issues related to it, and these same everyday Americans may one day sit on a jury and decide someone’s fate.”

Fordes, however, says that the Law & Order writing staffs he served on made efforts to diversify and accurately reflect the people and issues they wrote about. “Early on, the staff was full of liberal, progressive white guys, and we took great pains to maintain a good balance. As the staff became more diverse, the show clearly improved because of the broader perspective, but we maintained the overall view of no one is right all the time, and no one is wrong all the time.”

He points to a season 14 episode he co-wrote with a gay woman dealing with a same-sex female couple, murder, the right to adopt and child custody. “We wanted them to look like a regular couple,” he says. “It was important to us to show the gender identity or sexual orientation wasn’t important. It was about the desire to possess the child that warps the marriage. We always tried to portray protagonists and antagonists as human, fallible and uncertain.”

To address these concerns, some studios and shows are trying to be proactive and engaging with reform-minded groups. In August 2020, CBS announced it would hire 21CP Solutions, a police reform advisory group, to consult on its cop and legal shows.

That same year, Color of Change launched an initiative with actor Michael B. Jordan titled #ChangeHollywood to fight systemic racism in the entertainment industry. Color of Change has also hosted writers’ room consultations with the makers of several popular TV shows, including Grey’s Anatomy, 9-1-1: Lone Star, The Rookie, NCIS: New Orleans and S.W.A.T.

The Law & Order universe has not been immune from ongoing debates over how to reform the criminal justice system, especially the police. The 2020-21 season of SVU dealt with racial profiling, systemic reforms and even alternative forms of law enforcement. (In one episode, the Black deputy chief, who was promoted from a recurring role to the main cast at the start of the season, asks if social services has been called to the scene of a hostage situation in order to help de-escalate tensions, leading to a flat refusal from the cop on the scene.) In early May, NBC skipped the pilot phase and gave a straight-to-series greenlight for Law & Order: For the Defense. In an NBC press release, Wolf said he was excited to be able play defense after spending “the last 30 years on shows that played offense.”

It remains to be seen whether the new show will fall back on the tried-and-true Law & Order formula or seek to create a new one. Either way, it has something that many shows would kill for: a built-in, devoted and sophisticated fan base, thanks to its predecessors.

“I think our stereotype of a typical television viewer is that shows have to keep things simple, but Law & Order doesn’t do that,” Asimow says. “It’s quite remarkable to see how seriously it takes the law and how many viewers like that. Maybe some people like to watch it in order to learn about the law without having to go to law school.”

This story was originally published in the August/September 2021 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Law & Order Legacy: The franchise’s prime-time formula shaped a generation’s understanding of the legal system.”

Sidebar

Law & Order’s Top Prosecutors

Over the years, there have been many, many lawyers on Law & Order and its spin-offs. However, each show featured one main prosecutor who got most of the scenes inside and outside of the courtroom. Among them, just a handful appeared in more than 50 episodes across the Dick Wolf universe of shows. These are their stories:

Benjamin Stone. Photo by NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images via Getty Images

1. Benjamin Stone. Portrayed by Michael Moriarity (1990-1994, 88 episodes). The first lead prosecutor on Law & Order, the soft-spoken, by-the-book Stone was known for having a strong moral compass. While he wasn’t beneath taking the occasional shortcut, he also possessed a keen sense of social justice, which meant he was willing to lose in court if he felt that justice would be served. Stone resigned from the district attorney’s office at the end of season 4 after a witness he pressured into testifying against the Russian mob was murdered. Moriarity, who received an Emmy nomination for best actor in a drama series for each season he was on the show, had a tumultuous tenure and feuded with Wolf and others. He never made another appearance, and his character was killed off-screen in a 2018 episode of Law & Order: SVU.

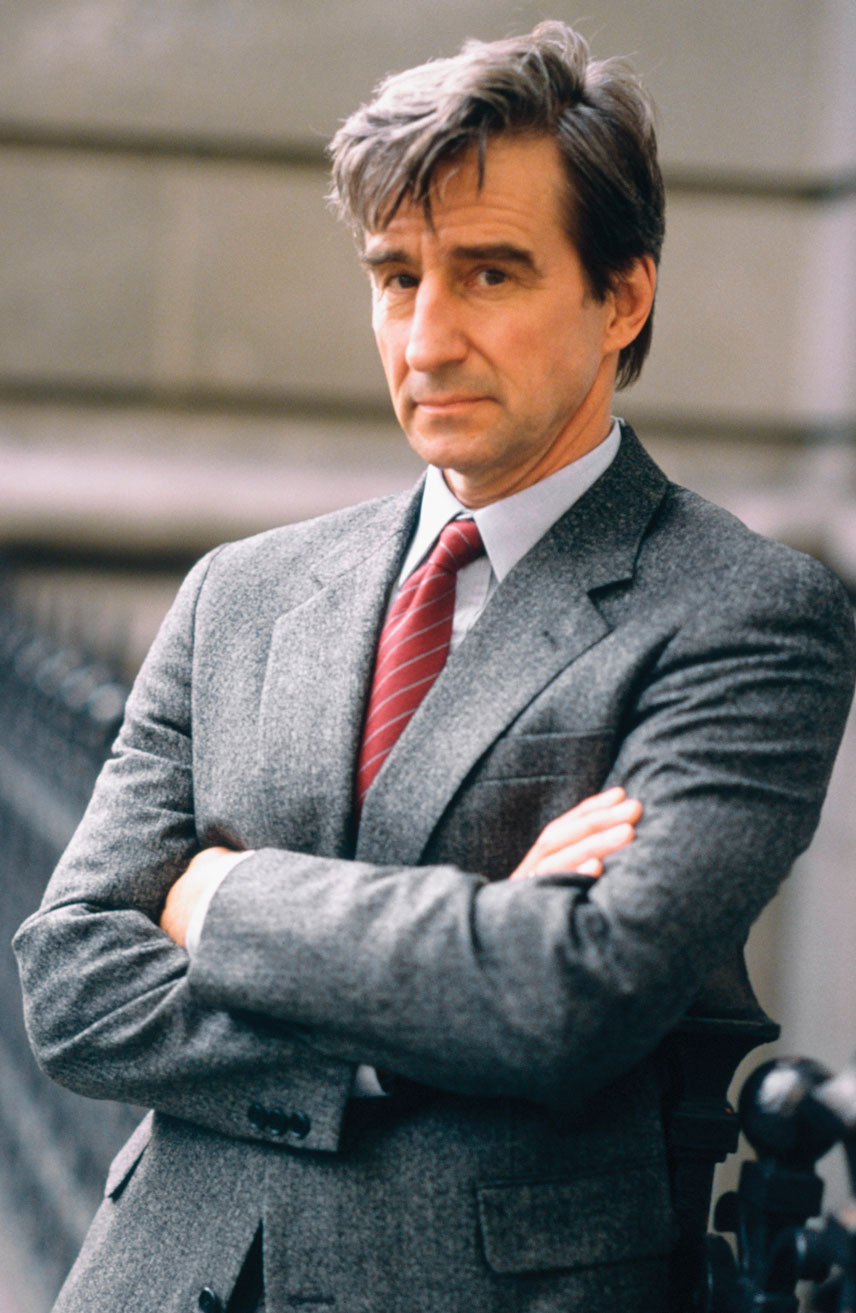

Jack McCoy Photo by NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images via Getty Images

2. Jack McCoy. Portrayed by Sam Waterston (1994-2018, 375 episodes, one made-for-TV movie). McCoy replaced Stone as lead ADA on Law & Order and proved to be his predecessor’s polar opposite. Brash and arrogant, he was a ruthless litigator who played to win, and many episodes dealt with his underhanded tactics and possibly unethical behavior. Despite his many run-ins with the bar, McCoy ended up as district attorney, serving in the top job from the start of the 18th season in 2007 until the show’s cancellation. Waterston was nominated for three Emmys for his portrayal of McCoy and won a Screen Actors Guild Award for best actor in 1999. When he made his last appearance in the Law & Order universe in 2018, he was still DA.

Alexandra “Alex” Cabot. Photo by: Virginia Sherwood/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images via Getty Images

3. Alexandra “Alex” Cabot. Portrayed by Stephanie March (2000-2018, 107 episodes). Cabot was the first main prosecutor in the SVU cast, compiling an excellent conviction percentage along the way. A stoic, hard-driving, by-the-book attorney, Cabot changed considerably after surviving an assassination attempt and going into witness protection for a time. She eventually returned, first on the short-lived Law & Order: Conviction and then back on SVU, where she displayed a more jaded, cynical attitude. She left the show but made a return in 2018 as part of a group that helps abused women fake their deaths to escape their partners.

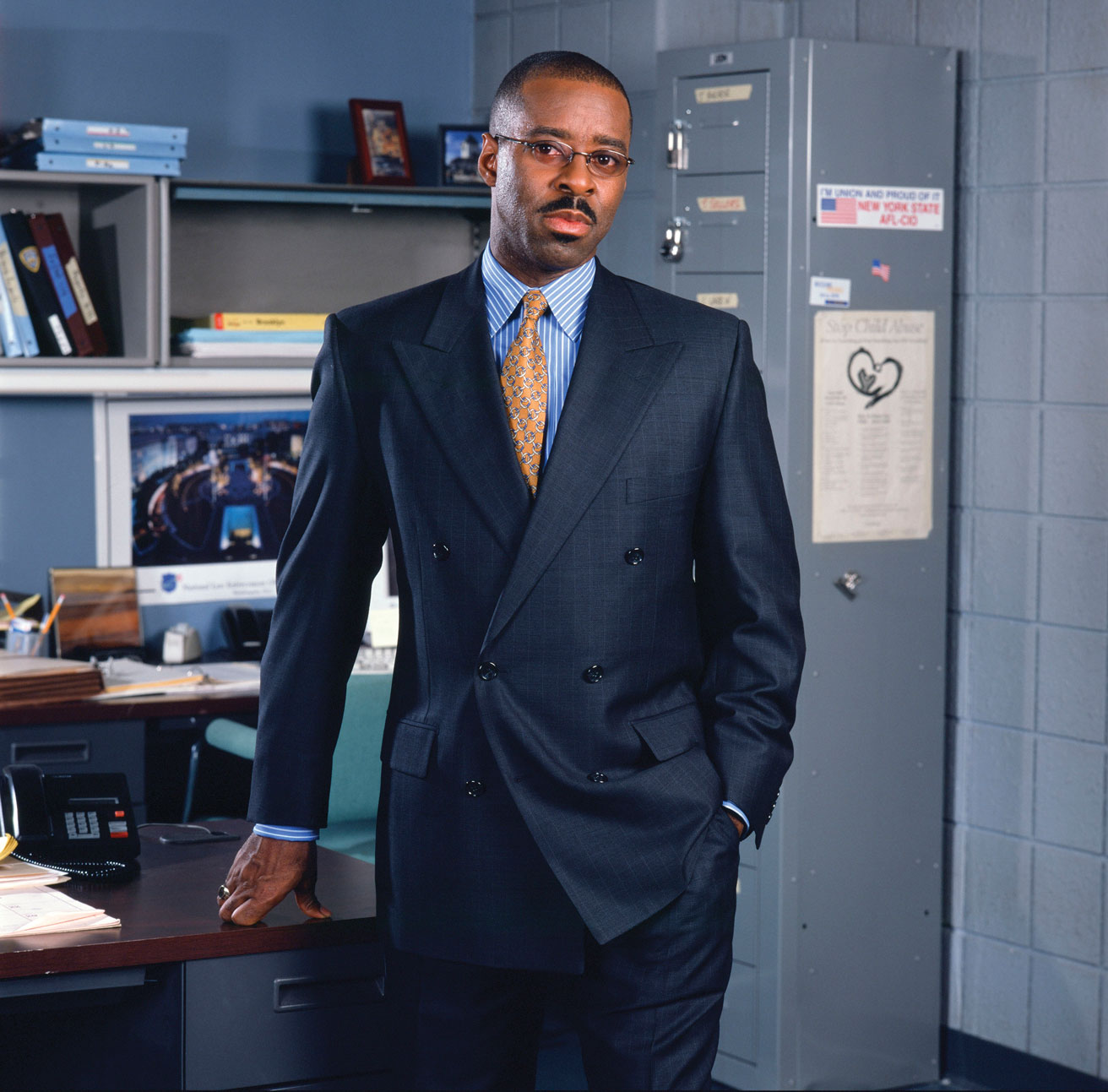

Ron Carver. Photo by John Seakwood/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images via Getty Images

4. Ron Carver. Portrayed by Courtney B. Vance (2001-2006, 111 episodes). The longest-running ADA on Law & Order: Criminal Intent, Carver was often a peripheral figure on the cop-centric show. Nevertheless, he was cool as a cucumber and wasn’t afraid to challenge the detectives in the major crimes unit when they were on uncertain legal terrain. He was written off without explanation after five seasons. Vance would later win an Emmy for portraying another litigator: Johnnie Cochran in The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story.

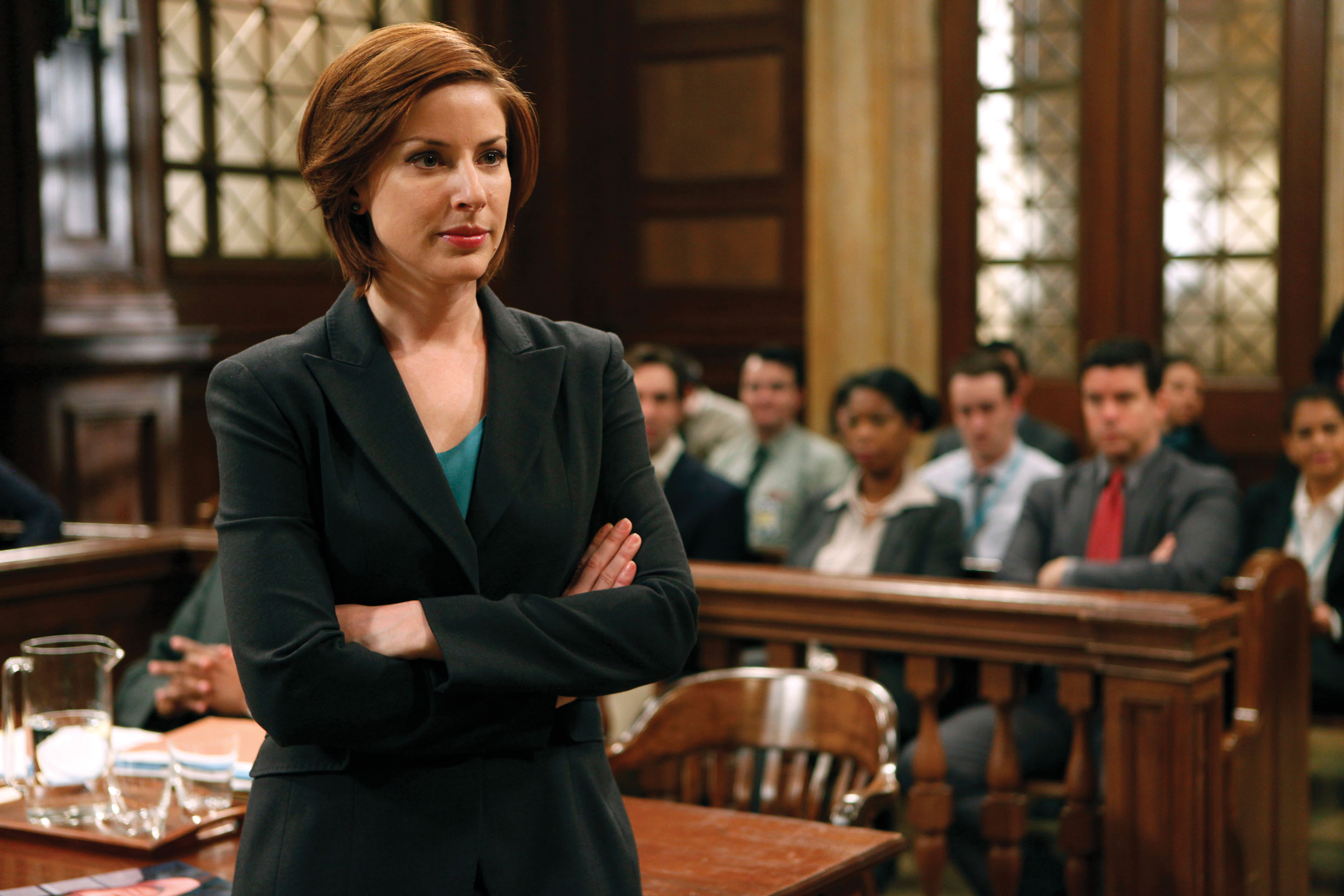

Casey Novak. Photo by: Craig Blankenhorn/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images via Getty Images

5. Casey Novak. Portrayed by Diane Neal (2003-2012, 107 episodes). The sharp-tongued, sharp-elbowed Novak replaced Cabot on SVU. Often deeply affected by her cases, the tenacious Novak was more than willing to bend the rules in order to get justice for victims. One such stunt nearly got her disbarred, and after serving a lengthy suspension, she returned to SVU with her reputation diminished. She was able to restore it, somewhat, and continued prosecuting cases. While her character was never formally written off the series, Neal has not made an appearance since 2012.

Michael Cutter. Photo by Virginia Sherwood/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images via Getty Images

6. Michael Cutter. Portrayed by Linus Roache (2008-2012, 67 episodes). The son McCoy never had, Cutter succeeded McCoy as lead ADA on Law & Order and was every bit as ruthless as his predecessor. His bare-knuckle style contrasted with the now politically conscious McCoy, and their conflict drove many of the late-season episodes. Cutter served as the top ADA until the end of the show. He made a few appearances on SVU, this time in a new position as bureau chief of the sex crimes unit.

Rafael Barba. Photo by Will Hart/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images via Getty Images

7. Rafael Barba. Portrayed by Raúl Esparza (2012-2021, 88 episodes). Dressed to the nines while possessing a sharp legal mind that often left his opponents at sixes and sevens, Barba combined style and substance as the main prosecutor on SVU. The fearless and no-nonsense ADA wasn’t afraid to put his own neck on the line—in one case, literally, as he allowed a defendant to choke him with a belt in open court in order to discredit him before the jury. He left his job in 2018 after being indicted for, and later acquitted of, murder after turning off a life support machine for a child suffering from a rare illness that had left him brain dead. He guest-starred in a 2021 SVU episode as a defense attorney.