by Dennis Crouch

Timothy Smith v. US, 21-1576 (Supreme Court 2022)

Some commercial and recreational fishermen place artificial reefs in the Gulf of Mexico to attract fish and increase their chances of a successful catch. StrikeLines is a small Pensacola, Florida business that collects and sells the coordinates of those artificial fishing reefs. The folks who place the reefs want them to be kept secret, but StrikeLines indicates that it discovers the reefs properly through analysis of various sonar datasets. Of some importance for this case, although Pensicola is in the Northern District of Florida, StrikeLines keeps its data on servers located in Orlando. Orlando is in the Middle District of Florida.

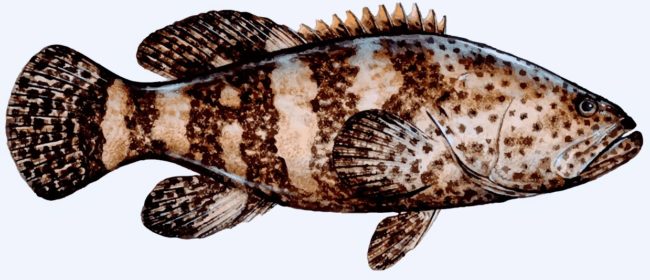

Smith is a software engineer from Mobile, Alabama. In 2019, he was convicted by a N.D. Florida jury for criminal theft of trade secrets and extortion (found not guilty for violation of the CFAA). Smith had discovered a vulnerability in the StrikeLines website and obtained many of the coordinates using a debugger known as “fiddler”. Smith messaged his friends and shared coordinates with friends. These facts constituted the basis for the trade secret theft charges. Meanwhile, Smith got in contact with folks at StrikeLines telling them about the breach and that he had the data. After some back-and forth (via phone messaging), Smith indicated that he would accessing the data and sharing it if they would give him the coordinates of a great spot for deep grouper fishing. This ‘ask’ served as the basis for the extortion charge. And, in the end, Smith was sentenced with 18 months followed by one-year of supervised release.

Throughout this entire time, Smith was in Alabama, not Florida. In his pending petition before the U.S. Supreme Court, Smith argues that venue was improper in Florida. The basis for his argument stems from the U.S. Constitution, which declares “The Trial of all Crimes . . . shall be held in the State where the said Crimes shall have been committed.” U.S. Const. art. III, § 2, cl. 3. The Sixth Amendment narrows this down further to the particular judicial district–requiring “an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed.” This same rule is found within Rule 18 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure: “the government must prosecute an offense in a district where the offense was committed.”

Smith appealed his conviction and the 11th Circuit partially sided with the defendant–holding that venue was improper on the trade secrecy claim, but was proper for the extortion charge.

In analyzing proper venue in Federal criminal cases the courts have a two-step approach: (1) identify the essential conduct elements of the crime; and (2) determine where those conduct elements were committed. Criminal trade secret theft has five elements:

- D intended to convert proprietary information for the economic benefit of someone other than the owner;

- The proprietary information is a trade secret;

- D Knowingly stole the trade secret or took it without authorization or by fraud or deception.

- D intended or at least knew that the offense would injure the owner of the trade secret; and

- The trade secret is related to interstate or foreign commerce.

Of these, elements 1 and 4 are mens rea elements rather than conduct elements and so the 11th Circuit found them irrelevant to the venue question. Elements 2 and 5 are qualities of the information, not conduct elements. Thus, the only conduct element is 3: “stole the trade secret or took it without authorization.” Under the U.S. Constitution, that the criminal trial must take place wherever that conduct occurred.

In its decision, the 11th Circuit recognized that venue is certainly proper in Alabama (where Smith was located) and probably proper in Middle-District of Florida since that is where the data was located when it was “stolen.” However, none of the essential conduct for trade secret theft occurred in Pensicola. Thus, “venue was not proper in the Northern District of Florida because Smith never committed any essential conduct in that location.” U.S. v. Smith, 22 F.4th 1236, 1238 (11th Cir. 2022). In the case, the Gov’t asked for an effects test — arguing that the company StrikeLines felt the effect of the theft in Pensicola. The court noted that some doctrines do apply an effect test for venue, but only in situations where the conduct elements of a criminal offense are defined in terms of their effects. Here, for instance, trade secret theft did not require harm to the TS owner as an element of the crime.

The extortion case was different since Smith had been directly communicating with folks via telephone in N.D. Florida. In that scenario, it is clear that the crime can be charged in either Smith’s location or N.D. Fla. The 11th Circuit also affirmed Smith’s jail term enhancement for obstruction of justice. Smith had testified that his exchanges were a “negotiation” and not extortion, and the district court found that to be false testimony.

Smith’s new petition for writ of certiorari does not directly challenge any of the 11th Circuit findings. Rather, Smith is concerned about what is next. In particular, the Government believes that a case thrown out for lack of venue can be retried in the proper venue. Smith argues here that venue was presented to the jury and that that the Gov’t should be barred from trying him again in Alabama. Thus, the question presented:

The Constitution requires that the government prove venue. When the government fails to meet this constitutional requirement, should the proper remedy be (1) acquittal barring re-prosecution of the offense, as the Fifth and Eighth Circuits have held, or (2) giving the government another bite at the apple by retrying the defendant for the same offense in a different venue, as the Sixth, Ninth, Tenth, and Eleventh Circuits have held?

Smith Petition. (Note the question above is the version used by the Amicus and is slightly more pointed). Another way to ask this question: What remedy is available for the Government’s violation of the constitutionally protected venue right? As prosecution for cyber-crimes continues to rise, the questions here continue to increase in importance.

The Conservative Rutherford Institute and Libertarian Cato Institute joined with the National Association of Public Defenders in an amicus brief. The brief argues that venue in criminal cases has been fundamental to criminal procedures for centuries dating back to the Magna Carta and that the 11th Circuit allowance for retrial undermines that right.

The Solicitor General’s brief in the case was due earlier this month, but the Court granted an extension until September 21.

The petition was filed by Samir Deger-Sen (Latham).

The crux of this case was it was a public website that required no password, had no terms of service and used google maps to display the coordinates. Everyone agreed the use of google maps required them to sent all coordinates to the visitors computer to display. So the data was never “under wraps”. hence the acquittal on the CFAA count.

> The folks who place the reefs want them to be kept secret, but StrikeLines indicates that it discovers the reefs properly through analysis of various sonar datasets.

IP law wise, I’m a bit surprised that StrikeLines can have a trade secret in the locations of (illegal?) artificial reefs built by other people in public waters.

I guess the lesson is, stay out of my favorite blueberry and morel mushroom spots. Or else.

Right — how is that a trade secret in the first place?

Seems like it easily meets the typical elements of a TS. I’m not sure how the fact that the underlying (no pun) reefs may have been illegally constructed has any bearing (no pun) on whether it’s a TS or not.

StrkeLines collected data on where there are good fishing spots, kept that data under wraps, and sold that data for a profit. That makes its data a trade secret.

The question of what makes those spots good fishing spots (including whether the spots are the result of artificial reefs being placed in those locations, legally or illegally) is irrelevant to the TS inquiry, as is the question of whether or not someone else could discover those spots on his own (obviously here he could). To analogize, in principle someone could reverse-engineer the formula for Coke, and sell his own product using that formula, but Coke’s formula would still be a trade secret as long as Coke continues to guard it.

?? Selling the data would actually take away any trade secret in that data.

Did you mean something else?

As I understand the facts from the CA11 opinion (background section), the collection of coordinates is sold off one-by-one. So yes, of course, once a set is sold, that particular set loses TS protection. But any existing or newly-generated unsold coordinates would remain as TS until they are sold. I think that’s what Atari Man means when he refers to “data under wraps” that is a TS.

Thanks for the clarification.

Fish have rights, too!

— DABUS

LOL. Thanks!

I wonder how the likes of Malcolm and marty (those that think that patent protection for “information” is the ‘worst thing ever’) feel about the criminalization of such “use of information.”

Do they just sit there and blink like Sheeple?

It does seem that a felony conviction is a bit harsher than a civil judgment of infringement.

But it has nothing to do with “Sheeple”, whatever those are.

You have no compunction about how anon continuously puts people down, yet complains no one wants to “debate” with him?

Moreover, that “Malcolm” and “Marty” apparently do not want to have patent protection for “information” means nothing with respect to their beliefs vis a vis codified trade secret law.

Yes please, let’s spare BobM’s sensitive feelings, even as he quite clearly misses the connection with “information.”

As to “whatever those are” — this sentiment marks you as one of them, BobM.

anon,

If my son now has the Trademark and files after a lawsuit, that too was the Atty with his NH dropped license’s responsibility.

Their silence screams volumes.

Yes, there is most definitely a logical connection vis a vis “information,” and the quick and vociferous reactions to the patent sphere while utter vacuum of reaction to other intellectual-property-related items IS very informative.

They have every opportunity to ‘chime in,’ and the fact that they do not reveals more of their ‘views’ than they may realize.

Comments are closed.