The metaverse is a new name for an existing idea. That is what Genevieve Bell asserted in an article for MIT Technology Review recently, noting the graduation of “metaverse” – i.e., the combination of aspects of social media, gaming, augmented and virtual reality, and the web that form “an immersive digital world” – from a “niche term to a household name in less than a year.” In fact, Bell states that “today’s conversations around the metaverse” mirror “a lot of the conversations [that were had] nearly 20 years ago about Second Life,” the 3D virtual world that Linden Lab launched in 2003.

Just as the metaverse is not a novel concept, many of the legal issues that are coming about in relation to this budding virtual world have been seen before, as well, including in conjunction with the rise of Second Life. In an article in the May/June 2009 issue of IP Litigator, Simon Holzer, a partner in Meyerlustenberger Lachenal’s IP team, addressed the unauthorized use of brands’ “real-world trademarks” on others’ virtual offerings. He noted that this was proving to be “an often-observed phenomenon” on Second Life, “particularly when a prominent brand decides to abstain from entering [the] virtual world.”

Pointing to Nike, Holzer revealed that in March 2007, searches for the sportswear titan’s name generated nearly 200 hits in third party-created Second Life stores (Gucci was not too far behind with more than 150 results). While “most of those hits linked to offers for virtual shoes for Second Life avatars bearing Nike’s distinctive swoosh, none of the virtual shoes were sold or authorized by Nike.”

Another “notorious” example cited by Holzer was the many versions of Cartier’s Himalia necklace, which were offered for sale in stores in Second Life for 10,000 Linden Dollars (the equivalent of roughly $37 back in early 2007) – albeit without Cartier’s endorsement. Similarly, Holzer noted the “omnipresence of virtual Swiss luxury watches,” such as those that replicated the offerings of Rolex, Patek Philippe, and Blancpain – again without the authorization of the watchmakers. As of the time of publication of Holzer’s article back in 2009, Hublot was the only watch company to have established an official presence in Second Life.

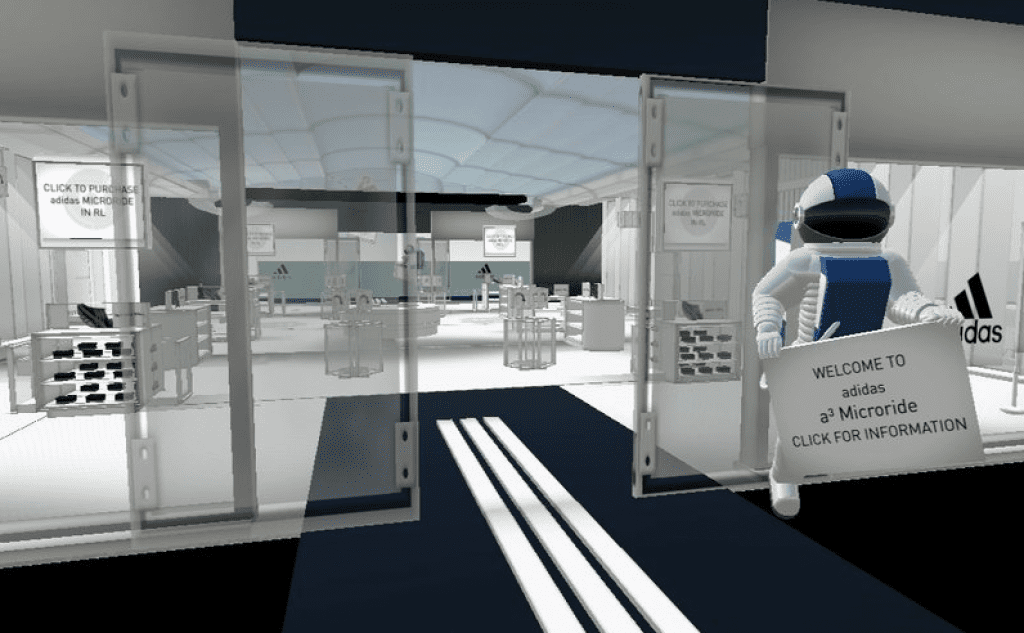

(Not unlike how brands are currently flocking to platforms like Roblox, Decentraland, Sandbox, etc. to connect with consumers and engage in a new(ish) revenue stream, Hublot was joined in the Second Life universe by IBM and Nissan, which acquired land on the virtual platform. Meanwhile, adidas and Reebok sold sneakers there, Toyota offered up virtual cars, Coke ran a marketing campaign there, 1-800-Flowers operated a floral pavilion and greenhouse, Toyota sold virtual cars, and Giorgio Armani and American Apparel offered up virtual clothing.)

The frequency with which brands’ trademarks were being used on the virtual goods in the Second Life ecosystem without their authorization unsurprisingly led to metaverse-related lawsuits. Taser International, for instance, filed a quickly-settled trademark infringement suit against San Francisco-based Linden Lab in 2009. Around the same time, virtual sex toy company Eros LLC filed a (since settled) trademark and copyright lawsuit against a Second Life user that was replicating its marks in the metaverse, and one against Linden, itself. Still yet, Cartier owner Richemont filed a trademark suit against an individual that was operating a store on the Second Life platform in which he offered up unauthorized Cartier-branded goods; that case ended after the defendant defaulted – again, leaving the merits of yet another one of the metaverse-centric lawsuits to come about in connection with Second Life untouched by the court.

Metaverse Lawsuits & Use in Commerce

Due to swift settlements or the defendants’ failure to participate, these lawsuits provided little insight into how courts would treat trademarks – and claims of trademark infringement – in the metaverse. However, another case, Bragg v. Linden Research, Inc., did shed light (at least tangentially) on one of the threshold – and still largely untested – issues when it comes to trademarks: Whether “use” of a mark within the Second Life sphere (or its more modern counterparts like Roblox) actually constitutes “use in commerce.” This is a fundamental issue, whether we are talking about Second Life or newer virtual worlds, as use in commerce is a both prerequisite to an entity amassing trademark rights and to making viable claims of trademark infringement.

In the Bragg case, a contract matter in which the plaintiff accused Linden of unlawfully confiscating the virtual property that he acquired on the platform (using “real world” dollars), Judge Eduardo Robreno of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania offered up some examples of what “use in commerce” could look like in the virtual world.

As Fenwick & West LLP’s Sally Abel stated at the time, in a May 2007 memorandum, the court outlined various ways that commerce exists in Second Life, stating that users can “buy, own, and sell virtual goods” on the Second Life platform, “create virtual goods and sell them for a profit,” “purchase virtual land, make improvements to that land, exclude other avatars from entering onto the land, rent the land, and sell the land for a profit” (and pay mandated “real estate” taxes to Linden in the process), and enter into “contracts and business relationships in the virtual world.”

Also suggesting that commercial use can occur within the realm of Second Life (and other virtual worlds) that seems to straddle the line between pure gaming/expressive use and commercial, the court acknowledged that Linden marketed the platform as a commercial space. It is also worth noting, as the court did, that the virtual currency in Second Life – Linden Dollars – can be bought with and could be sold for U.S. dollars, and that there was (and may still be) a secondary market for the L$ virtual currency on marketplace sites like eBay.

The broad language of the Lanham Act – which defines “use in commerce” as the bona fide use of a mark in the ordinary course of trade – may also suggest that the offering up and sale of virtual goods in a virtual world as “use in commerce.” Plus when you consider Second Life in the way that Reed Smith attorneys did in a recent guide – as “a large multiplayer role-playing game that also operates as an online economy, allows users to create their own virtual worlds, develop and promote intellectual property, and even sell their own branded creations (or those of others) for a profit” – it seems clear that some uses in the platform and others like it could be construed as commercial.

The same goes for the language that the Wall Street Journal used to describe the platform back in 2006. Writing for the WSJ, Andrew LaVallee stated that Linden Lab “has provided a platform for players to do whatever they want – whether it is building a business, tending bar or launching a space shuttle.” Beyond that, he stated that Second Life “residents [can] chat, shop, build homes, travel and hold down jobs” in the virtual world, and “are encouraged to create items in Second Life that they can sell to others or use themselves.” He noted that “Linden takes a cut of many in-world transactions (such as uploading a design to the game), and it charges players for ‘premium’ accounts, which offer more flexibility in owning land and displaying merchandise.”

An Avalanche of Uncontrolled Use

In much the same way as the striking rise of Second Life – which still exists and in fact, was the home for a New York Fashion Week-coinciding event for designer Jonathan Simkhai – brought with it no shortage of branding and trademark issues, virtual platforms that have come about since are giving rose to many of these questions (and a growing number of metaverse-related lawsuits), especially when considered along with the influx of allegedly infringing assets tied to non-fungible tokens (“NFTs”). But again, the fight against unauthorized wares in the virtual world may not be entirely uncharted territory.

As Amster Rothstein & Ebenstein, LLP partner Max Vern previously put it, “Unauthorized trademark use in the Second Life universe” – and other platforms – “can be compared to the avalanche of uncontrolled trademark infringements in [real] world jurisdictions suffering from ailing and ineffective trademark enforcement mechanisms.” Against that background, he says that brand owners should not view Second Life (or its more recent iterations) as “a petty or transient nuisance, but rather take a proactive position in enforcing their legitimate rights and curtailing encroachment, combining consumer education efforts with consistent trademark rights enforcement.”

As new metaverse-centric lawsuits, such as Hermès v. Mason Rothschild, start to make their way onto dockets and trademark applications for virtual goods and NFTs continue to flood national trademark offices, both of which will ideally shed light on how courts and examining attorneys view virtual marks (including the critical element of use in commerce), companies are generally being urged to establish a presence in the metaverse. Reed Smith’s attorneys encourage brand owners to consider “establishing a metaverse presence of their own,” as aside from the benefits that come with leveraging the metaverse as a way of reaching consumers and building brand awareness via a thriving and growing market, “it also provides an opportunity to monitor activity, and it may even help thwart trademark infringement by bad-faith actors.”