CyWee Group v. Google (Fed. Cir. 2021)

Google won its IPR challenge against CyWee’s U.S. Patent Nos. 8,441,438 (claims 1 & 3-5) and 8,552,978 (claims 10 & 12). On appeal, the Federal Circuit has affirmed with a short opinion by Chief Judge Prost focusing on three discrete issues:

Real Party in Interest: The patentee argued that Google did not disclose all real parties in interest as required by statute 35 U.S.C. § 312(a)(2). On appeal, the Federal Circuit held that institution stage real-party-in-interest questions are institution related and thus is not reviewable under the no-appeal provision of 35 U.S.C. § 314(d). This issue was previously decided in ESIP Series 2, LLC v. Puzhen Life USA, LLC, 958 F.3d 1378 (Fed. Cir. 2020). One difference here from ESIP is that the challenge was not raised to the institution decision itself, but rather as part of a post-institution motion to terminate based upon newly discovered evidence. On appeal though, the Federal Circuit found the new motion equivalent to a request to reconsider the institution. The court also held that the Board’s refusal to allow ESIP additional discovery was “similarly unreviewable” because the discovery ruling is tightly associated with the institution decision.

The court did not delve into the RPI issue, but CyWee was complaining about a coordinated effort by defendants in the district court litigation (including Samsung and Google) to ensure that Backmann was only seen by the Board and not also by Judge Bryson who was sitting by designation in the district court.

Approximately one month after Google filed its IPR petitions, Samsung dropped Bachmann from its invalidity contentions in the Samsung Litigation. This is consistent with what appears to be a coordinated effort between Samsung and

Google to block consideration of Bachman in the Samsung Litigation before Judge Bryson. Due to Bachmann’s shortcomings, neither wanted a summary judgement decision issuing from the district court, as CyWee’s lawsuit against Samsung was speeding toward trial and would outpace the Google IPRs. Dropping Bachmann from the Samsung Litigation assured that it could be addressed solely by the Board. This plan became more evident in January 2019 when, after the Google IPRs had been filed, Samsung moved to join the Google IPRs, thereby resurrecting its ability to rely on the Bachmann.

The PTAB concluded that this timing alone was not sufficient to find Samsung to be a Real Party in Interest and likewise found no RPI even though Samsung was being accused of infringement based upon its use of Google’s Android product. In its decision, the PTAB noted that the fact that Patent Owner had sued each company separately, in a separate lawsuit, also provided evidence that they are not real parties in interest. (I’d call this final conclusion quite tenuous).

Appointments Violation: The patentee raised an appointments clause issue, that was rejected under Arthrex (Fed. Cir. 2019). In particular, the Federal Circuit’s Arthrex decision purported to cure all appointments clause issues for AIA Trials that had not yet reached a final written decision. It is possible that this issue will get new legs once the Supreme Court issues its opinion in the case.

Obviousness: On the merits of the obviousness case, the patentee argued that the key prior art reference was not “analogous art” and therefore could not be used for obviousness. There are traditionally two ways to find a reference “analogous”:

- If the art is from the same field of endeavor, regardless of the problem addressed; or

- If the art is “reasonably pertinent to the particular problem with which the inventor is involved.” Bigio.

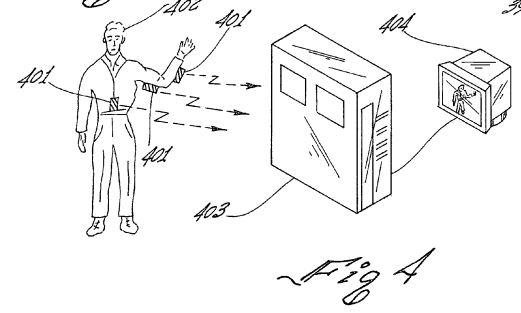

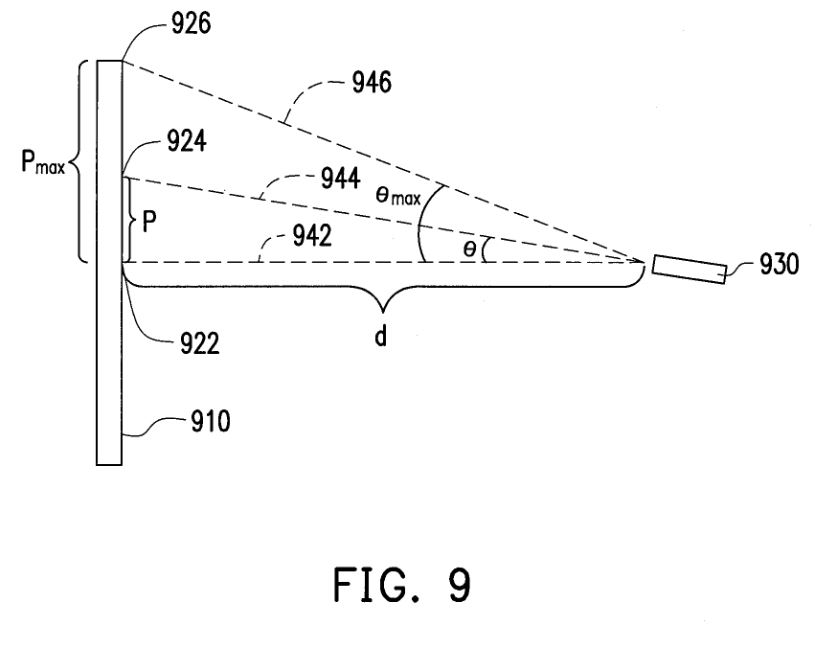

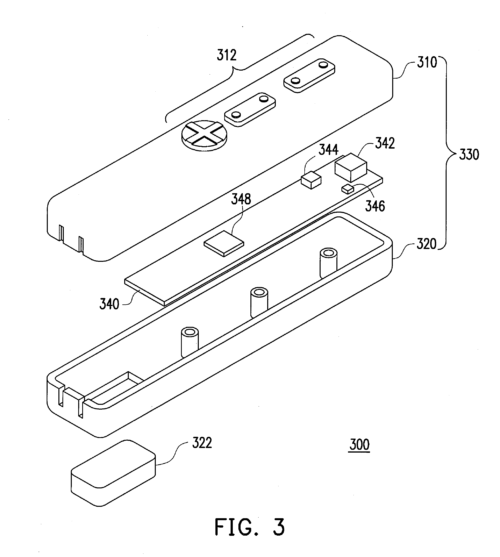

The CyWee patents cover a “3D Pointing Device” that uses a particular comparison algorithm for improved error compensation. The prior art (Bachmann, U.S. Patent No. 7,089,148), was created by the Navy and is directed to motion tracking of bodies. Thus, the PTAB found that it was not from the “same field or endeavor.”

CyWee argued that there were too many differences between its invention and Bachmann to allow the reference to be considered analogous. The Federal Circuit rejected that argument — holding that “a reference can be analogous art with respect to a patent even if there are significant differences between the two references.” Quoting Donner Tech., LLC v. Pro Stage Gear, LLC, 979 F.3d 1353 (Fed. Cir. 2020).

Note. Jay Kesan handled the appeal for the patentee; Matthew A. Smith for Google.

Note 2. The diagram looks a lot like a Wii. CyWee’s patents claim priority back to 2010 (Wii was released in 2006). [UPDATE – I had a big typo with a 2001 priority date. That would make a bit difference. Sorry.]

OT but Wallach, J. announced he’s taking senior status at the end of May.

Oh no. I can only imagine the science-ignorant, innovation hat ing, anti-patent judicial activists that SV will select and have Biden nominate.

Koh? That could be a consolation prize for missing out on CA9 during Obama. But Graber on CA9 is going senior so a spot is now open again.

Ed DuMont is another Obama appointee who didn’t make it.

Tara Elliott would hit the diversity criteria more squarely, and is of course well qualified.

But given Biden’s DE connections, I have to think Sens. Coons and Carper (a/k/a the C&C Legislation Factory) would have some input there. And seeing how Coons appears sympathetic to patentees, that could influence the pick.

You are dreaming. Silicon Valley will make the selection and Biden will dutifully to keep the money rolling in obey his masters and nominate whomever SV orders him to nominate.

My bet is that we are going to get someone over-the-top. Something of the order of a Lemley on the CAFC. Another Taranto.

Under Biden’s “equity” I’d imagine that SV will pick a “minority” women. Maybe that Chun woman out at San Jose state.

Actually that is probably who it is going to be. She is pals with Lemley and writes papers with him.

Chen I meant.

We’ll find out soon enough I guess!

It’ll also be interesting to see how the process plays out as this is one of Biden’s first appellate nominations and CAFC isn’t considered—at least conventionally and by the mass media, this blog etc. aside of course—to be particularly high stakes.

With the exception of the DuMont kerfuffle, all Obama’s nominees were confirmed in a very straightforward manner. I’ll be curious to see if anything has changed this time around.

“With the exception of the DuMont kerfuffle”

I can think of another Supreme exception…

I don’t know. Don’t underestimate the power of Big Pharma to get a pro-patent judge appointed.

Definitely agree. Especially right now they can probably leverage the happy feelings around the industry due to the COVID vaccines.

To anon, I was only talking about CAFC nominees. Apologies if that wasn’t clear. SCOTUS is a completely different story of course.

I hope you are right. You have no idea how much money SV poured into lobbying during the AIA to get the patent system bifurcated.

The bifurcation effort is not only coming from Big Tech.

Pharma would love to have their own set of rules, and if they could separate from general innovation, they would no doubt jump at the chance.

Speculation aside, I would love to know if anyone has concrete info about who the leading contenders are.

While this opening just materialized, I have to imagine that Biden and his team already had a short list drawn up to prepare for this eventuality. Not doing that just seems like contrary to basic political competence. So I am also very curious about the contents of that short list.

“Pharma would love to have their own set of rules”

Agree; but then again, with the ongoing and future convergence of pharma with computing (including machine learning, AI, VR, etc.) technologies . . . they’d best be careful about what they hope — and lobby — for.

Very. Careful.

>>On appeal, the Federal Circuit held that institution stage real-party-in-interest questions are institution related and thus is not reviewable under the no-appeal provision of 35 U.S.C. § 314(d).

This really bad since the RIP affects estoppel.

But there’s jurisdiction to review estoppel.

link to cafc.uscourts.gov

Thanks for the link.

A suggested practical analysis of what seems to be going on here: The recent clever tactic [yet to be challenged as inconsistent with Congressional intent] of avoidance of IPRs in patent suits by getting APJ discretionary institution denials based on unrealistically early suggested trial dates to decide the same validity issues has been met here by a clever counter-tactic.

[The attempt here to make the other defendant in the other suit a RPI in the IPR was bound to fail if they had no evidence of their controlling or paying for the IPR. And the IPR Petitioner had ample self-interest of their own.]

Analogous prior art is essentially dead letter law.

This is how it goes. First, let’s assume that the prior art reference is within a different field of endeavor so the inquiry becomes: is the prior art “reasonably pertinent to one or more of the particular problems to which the claimed inventions relate”?

The trick to the next step is to realize that every known element is in some way or form used to solve some type of problem. As such, element A can be used to solve Y problem (whatever Y problem happens to be). Once you’ve made that realization, it becomes trivial to argue that the inventors were concerned about Y problem. In reality, the inventor may not have worried about Y problem but instead was concerned about Z problem. However, that doesn’t matter.

Here it is in condensed form:

1) identify element from reference is different field of endeavor,

2) identify some problem addressed by element,

3) argue that the this identified problem was reasonably pertinent to the invention.

The hardest part is step 2), but anyone halfway competent with the technology should be able to come up with something. Personally, I like to make non-analogous prior art arguments — however, they are exceptionally, rarely successful at the PTAB.

This is what the Federal Circuit does these days — it takes doctrines that once could be used to help applications/patentees and they eviscerate them. For example, how often are ‘indicia of non-obviousness’ arguments successful at the Federal Circuit? While I’m thinking of it, it is not surprising to see this decision written by Prost.

Nothing in the statute requires prior art to be whatever “analogous” means. So to the extent that doctrine is “dead,” good riddance. If you are the patent owner the better argument is to just explain why the invention is not obvious, hopefully for some technical reason that the references cannot be combined, or one teaches away, etc..

Nothing in the statute requires prior art to be whatever “analogous” means.

Now if only that logic could be applied to 35 USC 101.

That being said, the theory is that one having ordinary skill in the art would not look to prior art outside of the art to which the invention pertains.

That is an interesting note – should we cast doubt on all of the Graham Factors?

I do remember way back when that a discussion was held that pointed out that Congress was rebuking the Supreme Court in the Act of 1952, and even though Congress set up 35 USC 103 to remove the Court’s wayward “Gist of the Invention” (and many many many similar terms), that the notes (I believe it was through the Cornell law website) indicated that some of the terms were ‘to be developed.’

It was not clear exactly whom would be developing these – but it should be clear that Congress – in rebuking the Supreme Court was NOT turning around and handing them back the keys to scriven on the topic.

I mean, having done scientific research, we look outside our field and to other fields for solutions to similar problems all the time. So if thats the theory, good riddance too.

And I dont think it’s that hard to get to something approximating current eligibility doctrine using textual analysis of USC 101. Looking at judicially recognized exceptions, for example: USC 101 requires an invention, and abstract ideas cannot be “invented,” so not eligible by text. Natural phenomenon may be” discovered,” but they cant be “new” by definition, so not eligible by text (obviously this raises the question of how you can discover something new, there is certainly some ambiguity there). Hence, judicially “recognized’ exemptions.

I think the big problem people have is with how courts try to figure out what the “invention” is in a given patent application. Some people seem to think they should just look at what was claimed and see if that fitss a statutory category– but its notable that 101 , unlike 102 and 103, does not use the term the “claimed invention.”

I mean, having done scientific research, we look outside our field and to other fields for solutions to similar problems all the time. So if thats the theory, good riddance too.

That’s already within the law.

Looking at judicially recognized exceptions, for example: USC 101 requires an invention, and abstract ideas cannot be “invented,” so not eligible by text.

That is a nice circular logic. We’ll add a non-existent requirement for an invention and when the Federal Circuit’s characterization of the invention doesn’t meet this requirement, it isn’t an invention.

35 USC 101 reads “Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.” In American Axle, for example, a process was claimed. This clearly falls with the scope of 35 USC 101. Is the invention new? Is it useful? Is it a process? If the answer to all of those questions are “yes,” as it was in American Axle, then then inventor “may obtain a patent therefor.” Mind you, this is “subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.” However, and very importantly, this doesn’t read “subject to judicially-created conditions and requirements.”

Natural phenomenon may be” discovered,” but they cant be “new” by definition, so not eligible by text (obviously this raises the question of how you can discover something new, there is certainly some ambiguity there).

Let me remind you of the text of the US Constitution — “To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to … inventors the exclusive right to their respective … discoveries.” So discoveries cannot be patented? Someone should have informed the Founding Fathers of this.

its notable that 101 , unlike 102 and 103, does not use the term the “claimed invention.”

Its notable that 101 is not a condition for patentability, and only conditions for patentability are a defense under 35 USC 282(b)(2). 102 and 103 are explicitly labeled as conditions for patentability. And 112 is explicitly mentioned in 282(b)(3). 101 is the go-to defense these days yet there is no reference to it in 35 USC 282(b). Why is that? The real reason is that it was never intended to be a defense.

In the House and Senate Reports on the revisions to Title 35 from 1952, the following was stated with regard to 35 USC 101:

A person may have “invented” a machine or a manufacture, which may include anything under the sun that is made by man, but it is not necessarily patentable under section 101 unless the conditions of the title are fulfilled.

Much of what the Federal Circuit has invalidated since Alice is “made by man.” While the Supreme Court has led the way, the Federal Circuit has taken the baton and used 35 USC 101 as flamethrower to eliminate wide swaths of subject matter from being patentable. 35 USC 101 was NEVER intended to be used in this manner. It wasn’t written like 102, 103, and 112 and the contemporaneous commentary regarding it never described it being used as a defense.

All of this is well-trodden territory. The big answer is that activist judges don’t care.

Another “big answer” is why does all of this “well-trodden” material have to be enunciated every time the topic comes up?

Why do we constantly have an anti-patent drum beat that explicitly and consistently ignores these points?

(and yet again this morning on my separate newsfeed I am served up an article by Meuer claiming that patents block innovation. How is this type of utter

C

R

A

P

allowed to continue?

Another “big answer” is why am I being selectively blocked on certain threads while the game playing of a particular poster (during and immediately after deep expungements based directly on this person’s games and cyber-stalking) is permitted, nay encouraged, to be a Heckler’s Veto?

Posting rules are not set objectively and then everyone gets to play by the same rules.

It is beyond clear that editing here is aimed at arriving at a certain desired narrative.

Ooooooh a conspiracy theorist !

LOL – Oh, please then, why don’t you come up with an ‘explanation’ of the objective facts of NON-objective editing practices.

I am eager to hear your ‘theory.’

Stunningly

“litig8tor” has no reply for the objective state of things.

Quick to exclaim “conspiracy” in his mindlessness…

A little bit of this: link to patentlyo.com

Or a little bit of that:

link to patentlyo.com

Which is theart should not be considered only a matter of fact. It should be a mixed question, like claim construction, because it gets right to the construction of the invention- or more indirectly, the construction of PHOSITA.

‘Do It On a Computer” inventions especially have analogous art issues. Are we talking about computer arts, or the arts being digitized as the more pertinent? Does stock trading software implicate financial experts or programmers? Does our PHOSITA have a mix of those fields? In what proportion?

“That being said, the theory is that one having ordinary skill in the art would not look to prior art outside of the art to which the invention pertains.”

I concur with you that the notion of “analogous art” is basically dead.

The death is the same type of death that drive the anti-patent Supreme Court prior to 1952 (the Court to which a member of that court dared to characterize itself — in a deprecating manner — as “the only valid patent is one that has not yet appeared before us.”

Congress sought to rectify this situation and admonish the Court by removing from the Court the power to use “Common Law” law writing in the sense of determining “invention,” or in a multitude of similar terms, “gist of the invention.”

Instead, Congress carved up the prior single paragraph and created separate sections, notably 35 USC 103.

The contours of 103 are before us now, and the SAME officiousness of “well, that does not deserve to be a patent” is playing out in the notion of analogous art.

Note that the original term was NOT “analogous art OR anything related to the problem.”

Innovation itself has long been understood to be properly generated by a cross-fertilization across different arts or areas of life.

This has been true across centuries. See the James Burke television show, “Connections.”

It is a “camel nose under the tent” that quickly leads to the entire camel being IN the tent to focus on “problem” as opposed to “art” when considering analogous.

By invoking “problem,” any sense of “art” is made to disappear, and you end up having the Flash of Genius (or pure serendipity) as being a requirement, because “solving a problem” is inherent in any innovation that provides utility.

The same type of slippery slope effect is easily recognized in those that mistakenly think that 103 art is merely 102 art in separate pieces.

Comments are closed.