The Alston Oral Arguments: A Citations-Focused Perspective

The NCAA antitrust case is likely to have major implications for intercollegiate athletics. Here's a look at the cases cited by the attorney-advocates and justices.

Ed. note: This article first appeared on The Juris Lab, a forum where “data analytics meets the law.”

Ed. note: This article first appeared on The Juris Lab, a forum where “data analytics meets the law.”

A little over a month ago, I brought to you the first part of a two-part series looking at the cases cited in the March 31 oral arguments for the forthcoming seminal college sports case NCAA v. Alston.

For those who have not been following this important litigation, Alston is an antitrust challenge to NCAA restrictions on athlete compensation on the grounds that restricting the amount and forms of compensation that can be made to college athletes in the name of “amateurism” is price fixing in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act. The case is likely to have huge implications on the governance scheme of intercollegiate sports in the future, especially over ongoing discussions surrounding athletes’ ability to commercialize their names, images, and likenesses (NIL) — discussions that have largely centered around whether the NCAA should receive antitrust protection to implement so-called guard-rails against NIL abuse by boosters and others looking for an end-around to more pure pay-for-play.

Generative AI In Legal Work — What’s Fact And What’s Fiction?

With the Alston decision likely to drop within the next few weeks, the time is certainly ripe to bring you Part 2 of this somewhat different approach into analysis of the Alston oral arguments: an approach that focuses mainly on the cases cited by the three attorney-advocates in their arguments in front of the courts, and what cases the justices themselves focused on in asking questions of those attorney-advocates.

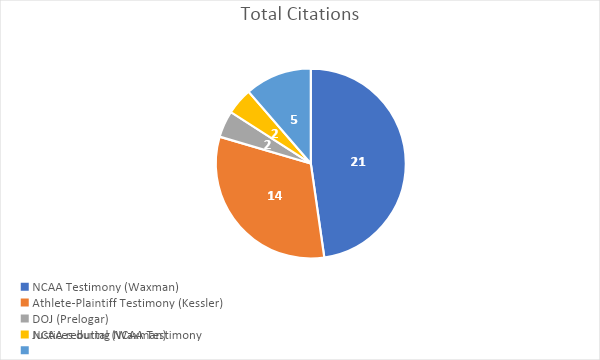

Last month’s Part 1 focused solely on the different cases cited during Seth Waxman’s argument on behalf of the NCAA petitioners. As noted in that earlier discussion, a strong majority of case citations made by the attorneys and justices during the entirety of the oral arguments (26 of 44) took place during Waxman’s initial argument.

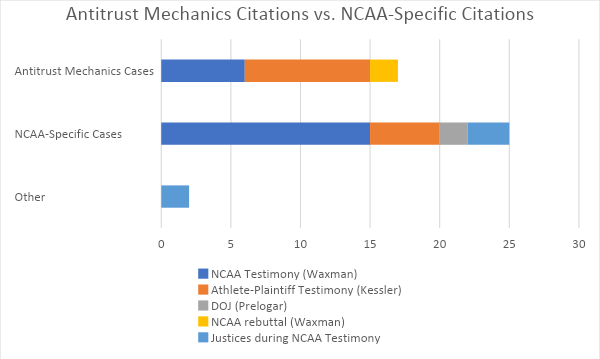

However, there were still quite a few notable case citations made during attorney Jeffrey Kessler’s argument on behalf of the respondent athlete class, most of which reflected the decidedly different approach he took to arguing the case. Indeed, while Waxman showed a preference to focus on discussions surrounding more generalizable antitrust mechanics — how and when the three-step Rule of Reason should be applied, for example — Kessler focused right off the bat on the more pure (and more narrow) NCAA immunity, immediately during his opening statement highlighting Justice Thomas’s questioning of Waxman about why the NCAA has not limited compensation for coaches while being more than happy to do so for athletes (citing the NCAA’s failed — and limited — attempt to do so that was found illegal in Law v. NCAA).

Sponsored

Is The Future Of Law Distributed? Lessons From The Tech Adoption Curve

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

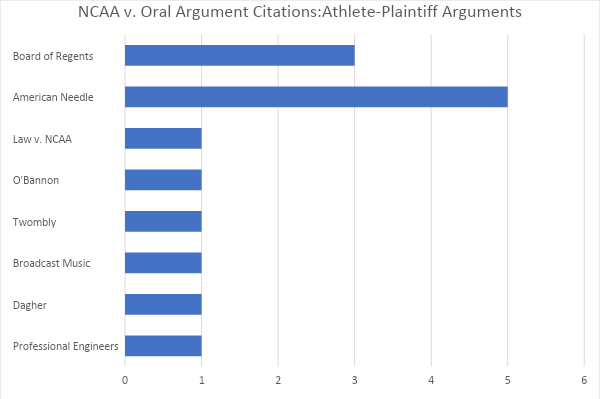

Interestingly, however, while Kessler was clear in his intent to shift the focus to the question of purported NCAA immunity under the antitrust laws — and the justices were more than happy to follow him there — Kessler did so in large part by citing more generalized antitrust mechanics cases rather than focusing mainly on NCAA-specific cases like Board of Regents and O’Bannon.

Part of this was based on the justices’ questions; Justice Gorsuch, for example, asked about the effects of an athlete-friendly decision on more general precedent establishing protections for joint ventures. Kessler responded by citing these cases — American Needle v. NFL, Texaco v. Dagher, and Broadcast Music v. Columbia Broadcasting System — to highlight that these protections are based in Rule of Reason analysis rather than giving the more threshold-level immunity that he claimed the NCAA was seeking.

But in the end, Kessler’s most-cited case — and one of the only two cases that he cited multiple times (along with the obvious NCAA v. Board of Regents) — was American Needle, another sports law case, but one that focuses almost entirely on the joint venture discussion rather than on any particular and specialized protections for sports leagues. Kessler would cite this case not only in responses to Justice Gorsuch and Justice Breyer’s questioning surrounding joint ventures but also in his opening statement alongside Board of Regents to argue that the Rule of Reason must apply in situations like those that he and the plaintiff class had challenged in this litigation.

Sponsored

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

Generative AI In Legal Work — What’s Fact And What’s Fiction?

In a way, this citation and discussion worked to twist a key component of the NCAA’s argument against itself: Even if the NCAA should be considered a joint venture and thus be afforded the special treatment under the antitrust laws that such a status allows, that treatment must still be balanced against anticompetitive harms and thrown into a least-restrictive alternative analysis under the broader Rule of Reason test. A quote from his closing statement where he argued that amateurism is “relevant here only insofar as Petitioners can show that it increases consumer choice by distinguishing college sports from professional sports” only served to drive this point home.