by Dennis Crouch

The Federal Circuit’s recent decision in IBM v. Zillow Group, Inc., — F.4th — (Fed. Cir. Oct 17, 2022) is a companion case another recent opinion, Weisner v. Google, — F.4th — (Fed. Cir. Oct 13, 2022). The two eligibility appeals were decided a days apart by the same three-judge panel of Reyna, Hughes, and Stoll following oral arguments held minutes apart. Both district courts dismissed infringement lawsuits at the pleading stage and the “abstract idea” question was up on appeal.

The two appellate opinions are also parallel. In both cases Judge Hughes concluded that claims were ineligible as directed to abstract ideas. Likewise, in both cases Judge Stoll concluded that the patentees had alleged plausible and specific facts showing that the claims embodied inventive concepts. As such Judge Stoll concluded that dismissal on the pleadings–before weighing any evidence–was improper. But, the two cases have different outcomes because of the third panel member, Judge Reyna. In IBM, Judge Reyna joined Judge Hughes’ opinion siding with the defendant. In Weisner, Judge Reyna joined Judge Stoll’s opinion siding with the patentee.

Read my post on Weisner: Dennis Crouch, Distinguishing Collecting Information from Using Information, Patently-O (Oct 17, 2022).

To be clear all three judges agreed that most of the asserted claims were invalid. The disagreement is over a subset that, according to Judge Stoll at least, the patentees made plausible and specific allegations sufficient to overcome a motion to dismiss.

Federal litigation begins with a plaintiff filing a complaint. In patent litigation, this is typically the patentee suing a defendant for patent infringement. Under the rules, the complaint must include a “short and plain statement … showing” that the patentee is entitled to relief. FRCP R. 8. In Iqbal and Twombly, the Supreme Court reinterpreted this rule to require nonconclusory allegations of specific facts that make the cause-of-action plausible. If the complaint fails this standard, the defendant can seek what was traditionally known as a “demurrer” and is now called a “motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted” under R. 12(b)(6) or “motion on the pleadings” under R. 12(c).

At the pleading stage, the court generally does not require the parties to provide admissible evidence to prove their factual contentions. But, one trick with patent eligibility is that eligibility is a question of law rather than a question of fact and the courts can require parties to prove-up questions of law very early-on in the lawsuit. This is especially true in the context of patent eligibility where, for the most part, the proof is intrinsic evidence such as the patent document itself and perhaps the prosecution history file. But, eligibility can at times also require consideration of extrinsic evidence, such as whether aspects of the claimed invention were, in-fact, already generic concepts to a person of skill in the art.

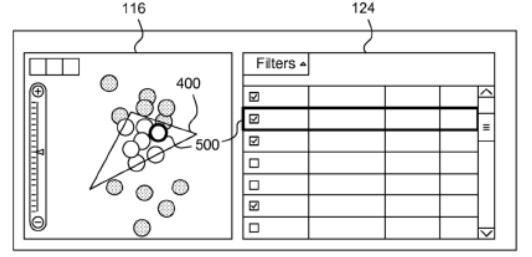

IBM’s asserted US7187389 claims a method of displaying layered data on a map. The image just above comes from IBM’s expert showing how the invention allows for ordering of the various layers, and for rearranging the layers as well and using non-spatial visual clues such as opacity to help show the layering. On appeal, the judges all agreed that the claims are directed to the abstract idea of “organizing and displaying information.” Although the particular method claimed may be novel, the court’s Alice Step-1 analysis explains that the claims do not recite any “improvement in computer technology” and instead relies upon functional steps such as “selecting” information; “identifying” information; “matching” information; “re-matching” information; “displaying” information; “rearranging” information; etc.

Such functional claim language, without more, is insufficient for patentability under our law.

Slip Op. At Alice Step-2, the majority inquired as to any specific inventive concept beyond the abstract idea itself (and found none). Here, the court again focused on the functional limitations that it found to be insufficient: “simply not enough under step two.”

In partial dissent, Judge Stoll looked particularly to claims 9 and 13 that focused on rearrangement of the layers and particularly required “rearranging logic” and “re-matching logic.” Judge Stoll then read the IBM complaint which explained how the problem of rearrangement of an overly cluttered display is not a simple task — especially once you begin dealing with a large number of objects. Although expert testimony is not normally needed at the motion-to-dismiss stage, eligibility is different and district courts are regularly allowing expert declarations. In this case, IBM actually attached its expert declaration to the amended complaint itself in order to preempt the eligibility challenge. The expert testimony explained the difficulty of rearranging and re-matching data in a way that is comprehensible on a display. The layers coupled with dynamic re-layering as claimed help solve this problem, according to the expert.

In her decision, Judge Stoll read IBM’s specific allegations as supported by their expert declaration and found them to make a plausible claim of a technical improvement sufficient satisfy Alice Step 2. As such, Stoll would have reversed as to those claims, as she did in Weisner.

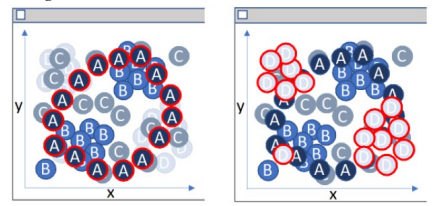

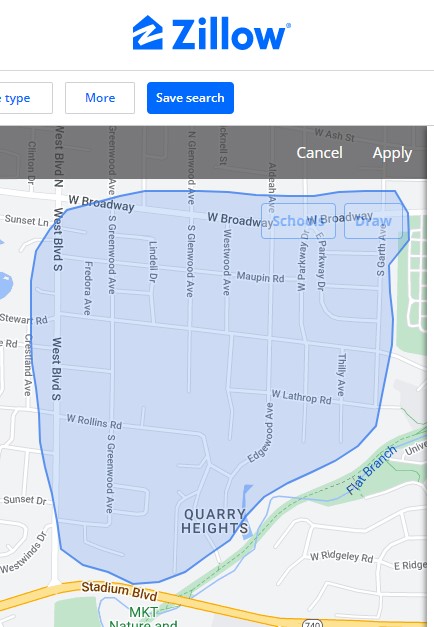

The second patent at issue is IBM’s US9158789 which claims a method of “coordinated geospatial” mapping. The basic idea is that a user draws a particular area on a map, and then is given filtered results specific to their particular selection. The figure above comes from IBM’s patent and shows how the user can draw a boundary (the triangle). The list is then populated with relevant results from inside the boundary. I used this with Zillow (the accused infringer) when looking for a house to buy in a specific area of Columbia Missouri. A screenshot of my neighborhood below (no houses for sale though).

Judge Hughes explains that the IBM claims are directed to the abstract idea of :

Responding to a user’s selection of a portion of a displayed map by simultaneously updating the map and a co-displayed list of items on the map.

Slip Op. In making this Step-1 determination, the appellate court significantly overlapped the Step-2 analysis–holding that the claims are “result-oriented” rather than directed to technical improvements. Once it dis reaching Step-2, the court found that the claims contained no inventive concept: The invention “was not directed to a computer-specific problem and merely used well-understood, routine, or conventional technology (a general-purpose computer) to more quickly solve the problem of layering and displaying visual data.” The court also read through the claim steps and found them to be functionally claimed–a loser under Step-1 and Step-2.

= = =

It is not clear why Judge Reyna sided with the patentee in Weisner but with the accused infringer in IBM. My best stab at distinguishing the two holdings is as follows. From these two cases, we might divide the claims into three categories:

- Collecting and organizing data (these are the invalid claims in Weisner);

- Collecting; organizing; and displaying data (these are the invalid claims in IBM); and

- Collecting; organizing; and using data (these are the valid claims in Weisner).

Reading between Judge Reyna’s sub silento lines, methods of use that go beyond mere display represent the type of invention that is more likely to pass muster.

Patent Memes’ daily contribution seems relevant to the discussions below.

link to twitter.com

As for Dozens (I Use My Real Name of Greg DeLassus, Except When I Don’t), there is zero relevancy with the twitter patent meme and what the “discussion below” is about — Especially noting how you have taken the position that you cannot read my posts (which everyone knows to be a

L

I

E).

What could be some of the reasons, that only an “average” cafc judge might use to invalidate a patent claim to the pictured memedevice? How can one wedge “abstractness” into the mix, to invalidate any claim possibly made to that device ? oh, just a mental calisthenic

Lol – I saw what you did there.

lol

I think we saw a few cases relating to hindsight with ref. to sec. 103 rejections, some of them cited in MPEP, concerning impermissible hindsight.

On the horizon, can we anticipate the possibility of some precedential decision …. eventually…… relating to sec. 101, and declaring a policy concerning “impermissible hindsight” in abstractness rejections alleged under sec. 101 ? I mean, clearly, to any patent examiner at the time, the Wright Bros. invention was certainly “abstract”, in the Examiners’ experiences (their minds lacked the necessary structure). It even took 5 years for the pto to issue their patent.

Sometimes I think that 33% or so of the abstractness rejections, are based on impermissible hindsight. It would be interesting to see the gifted legal minds of our time opine at some point on impermissible hindsight, in alleging abstractness rejections. 🙂

^^^ “that”

Wasn’t nearly so amusing.

One of your lesser musings.

Likely there is nothing to it, but… part of me is wondering whether some of the abstractness rejections may have a temporal element to them.

As in, can it be that what seemed abstract maybe XX years ago, would not be considered abstract today. And, some of what is considered abstract today, will not be considered abstract at some time in the future.

i.e., when (if ever) does an abstactness rejection need to consider “at the time the invention was made” ?

99.9% of me sees claim language as the source of abstractness, when present. Can “when the invention was made” ever be a factor in determining abstractness ?

Now that’s a bit more of an interesting musing (I will put it in my “the map is not the land” phlogiston and aether bucket.

Information has “structure” or it does not.

The patent act is silent about new, useful, non-obvious information.

All information is abstract. The utility provided by useful information is either abstract, or it’s not.

No human mind, no abstraction: the information is a machine component.

Utility within a human mind? Absolutely abstract.

Not sure why that leads to traffic lights but what we have now is gar bage in reference to new, useful & non obvious information.

Well marty, you continue to drown in your shallow (cess)pool of your particular colloquial views.

Let’s just contemplate a few things here:

“The patent act is silent about new, useful, non-obvious information.”

Please show me a claim that is “information” qua information.

You cannot.

Thus, your, “The utility provided by”is a nonstarter, as you have a errant view from which you begin.

Again (yes, yet again), you do not understand the terrain, with your, “No human mind, no abstraction”

In the Patent terrain, ‘No human mind ==> no ability to HAVE utility’ (as judging utility — in the patent sense — requires a human mind. This is exactly what you have been told before, and what Wt attempts to tell you below.

“Not sure why that leads to traffic lights”

And until you do, you will remain c1ue1ess about avoiding your embrace of your own reflection.

Your usual word salad. Didn’t get to the Printed Matter Doctrine this time, which is….an eligibility test, which exists because the patent act is silent about new, useful, and non-obvious information.

NOBODY understands the terrain jer ky, which is why we have articles like this one. Drowning a sea of re tar ded sexuality and bad poetry is YOUR thing….

We’ve been over this before, marty – just because you do not understand the law does not mean that someone explaining it to you is playing with “word salad.”

You simply do not get to choose what the law means based on how you want to “understand” (and I use that term very loosely for what you are doing) the law to be.

On top of the false accusation (one has to wonder what you think “word salad” means), you jump to a rather odd accusation of NOT getting to Printed Matter Doctrine, of which I have explicated in great detail (especially the critical exceptions to that doctrine). Typically I converse on that topic in shutting down Malcom’s wayward rants, so I am not sure just what you want with inserting that into THIS discussion.

And then you go frolic with your accusation of, “ Drowning a sea of re tar ded se x ua1ity and bad poetry is YOUR thing….”

It’s a bit scary if you are seeing ANY kind of

S

E

X

in the plain words of my explication – poetic or otherwise. Such would be ONLY in your own head, and simply leaves touch of the reality of this world.

Drowning a sea of re tar ded sexuality and bad poetry is YOUR thing….

Goodness, now you almost make me curious what I am missing.

Greg is a

L

I

A

R

or a f001 or both (his having directly replied to comments that he claims he cannot see and all)

“Information has “structure” or it does not.”

Can even seemingly-non-structured information be found to actually be structured ? It seems the mathematicians and statistical thermodynamicists have found, there is order even in chaos.

It seems to depends on the structures within the mind of the perceiver.

Less-structured minds can easily miss things apparent to others more structured.

That’s part of why the CAFC judges should have to pass the patent bar before ruling on patent matters imo, I wouldn’t want them to mis-apprehend things so critical as the engine of our progress.

No. Information either has structure, or it does not. If it does sometimes, but not other times, there needs to be a principled distinction.

That should be found in the use to which the information is put.

If a non-human actor gains utility from the information, its a machine component and has structure.

If a human actor gains utility from the information, it’s an abstraction and should be beyond the patent system, useful or not.

It’s all in the mind. What appears as unstructured info. to some is quite structured, in others’ view.

The ability for any machine to use human-generated info. is purely the product of human endeavor and Chakrabarty implies everything under the sun made by man is fair game. Can I patent a mere “ability” ? Of course. Every patent to a catalytic cracking method, on paper, is merely the conference of an ability, as all patents are required to do.

Human actor

A lab tech in electrochemistry followd my brilliant instruction and produced shiny brass from a non-cyan bath once, it was the first new use of the information which … I… created. Maybe I’m wrong but methinks I gave a human actor some info, and he gained the utility, in learning what I taught; it re-structured his mind to produce real stuff, and he never forgot it. Having those nice, brilliant brass-plated pieces in my hand, were hardly abstract.

I can “tell” the info also to an automated plating line, a machine. This machine can also produce non-cyan brass plated parts not previously produceable by machines.

haha, so what, who cares ? 🙂

Shiny brass is a mechanical or chemical change to the brass and you should be able to patent that- the infringing act is making or using the process to get shiny brass.

The infringing act is not telling someone how to make shiny brass.

Just a wee difference.

“Just a wee difference.”

Show me that claim to information qua information (second request this thread).

You know, “I claim the information of “X.”

Wee difference indeed.

…. especially in that statutory category that you so love to get wr0ng: process.

Somehow information (as information) is more than a wee different than ANY process.

But you keep on being you, marty.

Here Claim 1 from one of the issued patents contested. It is a claim for information only- there is no chemical or mechanical change to anything involved. The machinery used to actually display the information is not the subject matter of the patent, nor any change to that machinery. The only change is to the instructions sent to that machinery, and instructions are information. Go ahead, argue with that.

1. A method of displaying layered data, said method

comprising:

Selecting one or more objects to be displayed in a plurality of layers;

identifying a plurality of non-spatially distinguishable

display attributes, wherein one or more of the non

spatially distinguishable display attributes corresponds

to each of the layers; matching each of the objects to one of the layers; applying the non-spatially distinguishable display

attributes corresponding to the layer for each of the

matched objects;

determining a layer order for the plurality of layers,

wherein the layer order determines a display emphasis corresponding to the objects from the plurality of

objects in the corresponding layers; and

displaying the objects with the applied non-spatially dis

tinguishable display attributes based upon the determi

nation, wherein the objects in a first layer from the

plurality of layers are visually distinguished from the

objects in the other plurality of layers based upon the

non-spatially distinguishable display attributes of the

first layer

marty,

Could you display your lack of understanding in any brighter light?

The irony of your wanting to correct my pal Chrissy with your “Wee bit difference” and then turning around and confusing “a method of displaying” as being a claim for information only.

Clearly, the method of displaying is NOT information qua information.

That you think that this (somehow) supports your position only shows that you have zero c1ue as to what you are talking about.

Put.

The.

Shove1.

Down.

marty has no answer – and runs away.

What are the chances that he will not learn his lesson here and will (mindlessly) repeat his out of touch views yet again on some future thread?

Hint: substantially greater than “wee.”

Utlity in the patent sense is NOT how you are trying to colloquially phrase this “gain utility from” nonsense – as evident by your circular insertion of “useful or not.”

Your “should be beyond the patent system” has no tether. Come up from embracing your reflection. You cannot dig yourself out of the hole of your fallacy, no matter how diligently you shove1.

Below in the Comment Four series, marty’s odd penchant is (again) rebuffed.

But there is a teaching moment here, while somewhat tangential, can be appreciated.

It is well known (to those serious about protecting innovation) that in the computing arts, AN innovation can — and often is — claimed in more than one statutory category.

The “colloquial” may well view this as granting a single patent to more than one invention when the claim set includes more than one statutory category (for example, device, system and method).

But this plain legal error is only because “the colloquial” refuse to recognize the legal terrain.

To wit (and more to Malcolm’s perpetual whine about “soft”ware:

For those that whinge at software, here is a direct hardware equivalent:

link to venturebeat.com

The method of generating the method is a process. A computer configured to generate the menu is a machine. What’s your point?

My point is that rearranging a menu is not an activity that should be protected by a patent. I assume you know that’s my point.

Regardless, almost all “utility” happens in the human mind.

Really? An alloy that does not rust? The utility happens in the human mind?

A device that helps mend a broken bone? The utility is in the human mind?

Ok then.

Better menus? Better stock picking interfaces? Better maps in the mall?

hmmmmmmm

But my menu generator uses remotely secured dynamically weighted keystore objects.

… which may or may not be an advance (but is certainly the type of thing that is patent eligible, eh).

Yet again, Malcolm, please feel free to abstain from anything that you would deem not eligible for patent protection (which does include most all computing, including not only any online commercial transactions, but your kvetching online as well).

Marty,

Keep on being you and pretending that your colloquial view of utility has merit for patent law discussions.

My best guess is maybe the expert testimony in one case but not the other influenced Judge Reyna.

And Judge Reyna having no scientific training or experience with patents prior to his appointment on the CAFC is certainly the one to be making finding of fact for expert testimony.

Are CAFC Judges themselves required to pass the patent bar ?

No, they are not. And Obama appointed a bunch of judges that didn’t even have a science background. Reyna was the worst one where he had no science background and no background in patent law.

oh, what an absurdity, to think, a mere baccalaureate in ______ major just out of college who passes the patent bar, has more credentials on the matter than a Judge rendering decisions.

Why, just the other day I heard a newly-minted patent agent say something smarter than a CAFC judge on a patent matter. har har har, a real knee-slapper !!

How deep does the rabid hoe go ?

FWIW, former Chief Judge Randall Rader was an English major.

Of one knows and understands their limitations, the degree below is less impactful.

I believe that what Night Writer wants to assert is that those on the bench WITH limitations of patent knowledge are NOT acting in accord with that limitation, but instead are acting with a “patents be The Bad” narrative.

I took a class from Radar other.

Radar was an exception who spent a great deal of time to understanding the inventions and their advantages.

He worked hard at it and understood that science was tough.

A lot of the great lawyers were English majors originally. Can’t name any off the top of my head, but recall having read biographies of many and only recall the sensation of “wow, a lot of english majors sure made good”. oh, Mr. Bauer, former Gen’l Counsel of Lubrizol, was an eng. maj.

I sense a fresh mind out of law school could probaby do the patent bar in like 8 weeks maybe but in any event less than a year’s time.It just seems a bit gauche’, or improper that judges not possessed of even that level, are judging patent cases. Then again, maybe they don’t need to know that pesky patent stuff 🙂

The thing to remember about the CAFC is that it was formed out of the merger of the CCPA and the Court of Federal Claims Appellate Division. Therefore, while we tend to think of the CAFC as the “patent court,” it also handles all international trade disputes, government employment disputes, and Tucker Act claims. Just as it makes sense to have CAFC judges with science backgrounds and patent law experience, it makes sense to have CAFC judges with experience in international trade. Judge Reyna was a leading advocate in that field when he was appointed to the CAFC. Complaining about his lack of patent experience makes as much sense as a trade lawyer complaining about Judge Newman’s lack of trade experience.

Greg, I think the problem is that many on the CAFC seemingly have no interest in creating a workable set of patent laws. They appear to be focused on trying to limit the patent right.

It is a problem that the CAFC has more jurisdiction outside of patent law. I believe, though, the intent of the CAFC was to only seat judges that did have proficiency in patent law and science.

I believe, though, the intent of the CAFC was to only seat judges that did have proficiency in patent law and science.

If that was the intention, why did the inaugural bench of that court have so few science/patent-experienced judges? Go ahead and look at the biographies of the “operation of law” appointments to the CAFC. Those are the original judges. Fewer than half of them have any listed scientific education.

It is a problem that the CAFC has more jurisdiction outside of patent law.

On this we agree. I would prefer that there be a specialty set of district courts set aside for patent cases, as well as a patent-specific appeals court. I would even prefer that this specialized appeals court be outside of the SCOTUS’ jurisdiction for review. You and I seem to be distinctly in the minority on this point (although we may be in the majority around this blog’s comments section).

The federal judiciary conference has an (irrational) allergy to “specialized” courts, because they consider that it promotes “tunnel vision.” There seems to be a broad consensus among those who matter that it is important for judges to preside over a variety of different sorts of cases. More’s the pity…

Judge Rich majored in economics at Columbia. I think that it would be good to have a specialized set of science-educated judges for handling patent disputes, but there is no denying that many of our better patent judges in the past have had notably little science education (e.g., Learned Hand, or Joseph Story).

The goal would be to reduce the number of spurious decisions, by increasing the quality of the court.

Reckon, we all know lawyers who’ve been miffed, bewildered, surprised, etc., by some decisions.

I’d maybe question whether requiring a court deciding patent matters, to be constituted of at least 1/3 experienced patent lawyers, would result in higher-quality and more-consistent decisions, in the long haul.

It seems like it would. It seems prima facie obvious that anytime the knowledge / experience level of a group of people is increased in their specialized area, the quality of their work product would also be expected to increase, since knowledge is an art-recognized, results-effective variable !

But, nobody ever claimed they were specialists 🙂

“Why does the recent rise in patent filings not track with productivity growth? Because the average creativity of patents… has been declining for decades.”

Talk about your application spot for Pauli’s “not even wrong”….

Greg (Dozens) left out the “stated metric” (which is BOTH nowhere defined, AND features a graph that squarely falls into the “how to prevaricate with data”).

Nice job there Greg, you Liberal Left anti-patent lemming.

average creativity maybe is irrelevant, since what society rewards, are the exceptional ones, and not mediocrity.

Growth in productivity is subject to forces external to the patent system, viz. increased bond rates can translate to higher unemployment and a whole slew of other effects on productivity.

Perhaps you’re suggesting that there seem to be fewer “pioneering” type of inventions these days ? I’d say yes to that, tech has seemingly reached a plateau. Maybe we live during times of “Peak IP”, analogous to “Peak Oil”.

average creativity maybe is irrelevant, since what society rewards, are the exceptional ones, and not mediocrity.

“Average” creativity is necessarily a function of both the high and low ends of the spectrum. Therefore, the average cannot be “irrelevant,” even in a model where the high end is the part that we reward.

Growth in productivity is subject to forces external to the patent system, viz. increased bond rates can translate to higher unemployment and a whole slew of other effects on productivity.

Definitely. It could be that productivity is declining for reasons that have nothing to do with the sorts of technology that drive the growth in patent grants. It could be, for example, that productivity’s “natural” rate of decline is even faster, and that the growth in patents is the only holding it to a steady decline instead of precipitous collapse. Precisely because the unassailable, observed facts are susceptible to multiple explanations, that is the reason that the proposed explanation is potentially interesting.

But also, why the h do we need so much productivity ? Is there a potential point when there is “too much productivity for our own good?”

What if we took the Henry Ford school model, exported it worldwide and had everybody everywhere, just producing producing producing all sorts of things….When does one say “ok, enough” ? There’s an old Iron Mountain report discussing the problems surrounding excess production, its a huge topic.

I saw recently where since foundation of the NEA, the rank of HS graduates worldwide went,, in the usa from #1, down to like #17 since 1979.

I don’t see creativity as a valid metric due to that term’s breadth, more qualification is needed, because a huge subset of “creativity” is creative garbage, crapola ! I prefer to think in terms of commercially-valuable technology 🙂 One beauty is that the biz. environment (business climate) constantly changes, which requires the ‘creative’ ones to themselves constantly evolve their thinking. I suspect the population of those able to continually evolve themselves in that sense is smaller that in the past. hava good day.

Chrissy, your point of,

“I don’t see creativity as a valid metric due to that term’s breadth, more qualification is needed,”

is exactly the type of thing that Greg’s recent reference to Wolfgang Pauli’s “Not Even Wrong” applies.

However, Greg has shown himself to be less intelligent than a puppy, and shoving his nose in his own B$ is not likely to have him change.

[W]hy… do we need so much productivity ? Is there a potential point when there is “too much productivity for our own good?”

There is never a point at which we have “too much” productivity. “Productivity” is just the amount of work needed to produce X standard of living. If it takes 10 man-hours this year to make a bushel of corn, and 9.5 man-hours next year to make the same bushel, then that is an extra 30 min. of leisure that someone can enjoy while still producing the same amount of corn for us all to eat. More productivity = more leisure, and more leisure is always a good thing.

I don’t see creativity as a valid metric due to that term’s breadth, more qualification is needed, because a huge subset of “creativity” is creative garbage, crapola ! I prefer to think in terms of commercially-valuable technology 🙂

I definitely agree, which is why it is significant that Kalyani’s measure of “creativity” correlates with stock market valuation of the patentee firm. Evidently, he has identified a measurable independent variable that is not merely a stand-in for “creative” varieties of finger painting or what not, but rather of market-rewarded technological progress. That is what makes the paper interesting.

The omitted parenthetical renders the post much less interesting.

Three replies:

(1) Fair enough, of course. What is “interesting” is a matter of personal taste, so it is not for me to tell you what interests you.

(2) I am not actually endorsing the linked thesis by linking it. I found it interesting, so I am passing it along on the chance that it might interest others around these parts.

(3) The reason why it interested me is because those of us who favor the patent system as it presently exists (a class among whom I count myself) tell a story about how patents promote improvements in technology, and the improvement in technology improves all of our lives. That is the social compact that underlies the patent system: the people of a given jurisdiction agree to submit themselves to a certain, limited restraint on trade/competition, in return for which the enjoy the benefits of economic growth. Critical to that bargain is that the benefits from the economic growth outweigh/outpace the detriments that come from the restraint of trade/competition.

Is this true? We really should care whether this proposition accurately describes reality, but it can be hard to measure. To the extent that the granting of patents continues to grow, while economic progress begins to level off, that would suggest that the patent bargain is breaking down. That patent grants are growing while productivity declines is an observable fact. The linked thread attempts to explain why that observed fact is occurring. The proposed explanation may be convincing or unconvincing, but the actual phenomenon being explained cannot be dismissed, and that is the part that I find most interesting.

Sure – b-b-but Greg (Dozens) is always on the up-and-up.

What’s really funny here is that the provided metric of “novel arrangement of key words” being on a marked decline speaks against Malcolm’s oft lament against the computing arts of “making up new words” — given that the greatest number of advances over the same timeframe have been related to the computing arts.

Incidentally, does it affect your “less interesting” characterization if the author is correct that only “the share of two-word combinations that did not appear in previous patents… are associated with significant improvements in firm level productivity and stock market valuations”? It seems to me that this correlation between his measure of “creativity” and two real-world dependent variables (firm level productivity and stock market valuation of a firm) suggests that he has not merely hit on an arbitrary definition of “creativity,” but that this is actually touching on the real entity.

Will somebody who knows Greg (I Use My Real Name Along With Dozens) DeLassus – anybody – suggest to him in person to stop cratering his reputation?

Here (for example): “ ‘Average’ creativity is necessarily a function of both the high and low ends of the spectrum. Therefore, the average cannot be ‘irrelevant,’ even in a model where the high end is the part that we reward.”

This is utter nonsense and shows that Greg does not understand simple numbers.

Let’s do a quick example on averages.

Suppose for this example that we have manufacturing runs and are interested in our batch throughputs.

(Batch size can be scaled, but for now the measure is on the complete batch)

We run four batches. The first three are a consistent (and desirable) 0.99 throughput. However, the last batch goes wrong and yields a zero throughput.

Average in this case is a mere 0.74.

This is just NOT a number worth too much.

Take the same set-up. This time, the first NINE batches are a consistent (and desirable) 0.99 throughput. However, the last batch goes wrong and yields a zero throughput.

Average in this case is a mere 0.89.

Greg appears to want to use the average as reflective of the process. Clearly using an average without accounting for outliers (and appropriate treatment thereof) yields nonsense.

It should be noted that this thing of “interest” to Greg is run-through with the type of fallacies that one finds (too often) in academics who have no real appreciation of the subject matter.

Further, Greg’s own lack of understanding of logic yields him accepting a conclusion (NOT properly reached) with his comment of,

“ whether this proposition accurately describes reality, but it can be hard to measure. To the extent that the granting of patents continues to grow, while economic progress begins to level off”

And his further nonsense of (my emphasis added),

“if the author is correct that only “the share of two-word combinations that did not appear in previous patents… are associated with significant improvements in firm level productivity and stock market valuations”? It seems to me that this correlation between his measure of “creativity” and two real-world dependent variables (firm level productivity and stock market valuation of a firm) suggests that he has not merely hit on an arbitrary definition of “creativity,” but that this is actually touching on the real entity.”

He (blindly) accepts as cause that which is (at best) P00RLY is presented as correlation (and a correlation that itself is clearly a fallacy – “novel word pairs’ – really?).

That does sound interesting. I remain deeply skeptical, but it’s interesting.

One should always be skeptical of social-science research.

Not sure I buy the metric of evaluating patents by the combination of elements used in the claims.

I do not think that the analysis was confined to the claims.

^^^ you could have stopped with your first four words, Greg “I Use My Real Name and Dozens.”

methods of use beyond mere display…..hmmmmmm. I wonder if that implies that there are different forms of utility.

Once again, absolutely no way to predict or repeat an appellate finding beyond the glint in a jurist’s eye regarding the subject matter of a putative invention.

And a Wild West procedural jungle entirely idiosyncratic to the district court involved. Sometimes experts, sometimes not. Sometimes mixed matter of fact and law, sometimes not. Sometimes the four corners of the patent and complaint, sometimes not.

Markman cleaned up a similar m ess. There should be a formal construction step where the invention- as opposed to the claims- is construed.

Until its clearly recognized that inventions and claims are subject to different forms of abstraction, this m ess will continue.

Maps used by people are always abstract, 1000%.

“Maps used by people are always abstract, 1000%.”

In the patent sense, so are traffic lights.

In the words of the immortal Homer,

D’0h!

Patents to a GPS — balderdash. All you are doing is determining your position in space. People have always done that. Moreover, GPS patents do not necessary recite “using” the information.

These are silly distinctions.

If you want a test consistent with the US Constitution, then ask these questions:

1) Is the invention a product of human ingenuity?

2) Is the invention the type of activity that we (the United States) want to encourage people to create more of?

If you want to exclude from this set things such as human speaking or human thought, then go ahead and do that.

What gets lost in the minutia of these Federal Circuit decisions is how the policy concerns that justified the earlier decisions have been jettisoned. This is some of the language from Gottschalk v. Benson:

“[w]hile a scientific truth, or the mathematical expression of it, is not a patentable invention, a novel and useful structure created with the aid of knowledge of scientific truth may be.”

“[a]n idea, of itself, is not patentable.”

“A principle, in the abstract, is a fundamental truth; an original cause; a motive; these cannot be patented, as no one can claim in either of them an exclusive right.”

Phenomena of nature, though just discovered, mental processes, and abstract intellectual concepts are not patentable, as they are the basic tools of scientific and technological work.

Are any of these patents preventing “the basic tools of scientific and technological work?” Are any of these patents attempting to patent “[a]n idea, of itself”? Are any “fundamental truth[s]” being patented?

The answer to these questions is “no.” These patents are describing and claiming man-made tools. These are the type of tools that provide some particular benefit to humans. And in general, people want more of these tools (i.e., promote the progress of) — not less. As such, the patent system should encourage the development of these tools by granting valid patents thereon.

If a test for patent eligibility involves any additional questions than the ones I described above, then that test is a poor one and does not reflect the fundamental purpose of patents as stated in Article I Section 8 Clause 8 of the US Constitution.

“[w]hile a scientific truth, or the mathematical expression of it, is not a patentable invention, a novel and useful structure created with the aid of knowledge of scientific truth may be.”

mmm hmmm. Is a stock trading GUI a novel and useful structure?

The computer is. The GPS satellite is. A method of operation- be it hardware or software based- that compares time signals and renders a position that is novel and fully described should be. But is the menu on your smart TV actually a structure, no matter how clever and pleasing ?

Abstract intellectual concepts and mental processes are not merely “Ideas” with capital I. The realm of the human mind is where the patent system should not trespass, and when utility happens within a human mind, it’s not a technical result- its more akin to art or expression, despite the utility that some people may derive. Utility within a mind is different for all minds.

The utility of an accurate position reading is the same for all non-human minds.

One is potentially justiciable, one surely is not.

Martin, it is a shame that you can’t separate “The realm of the human mind is where the patent system should not trespass” from structure that is created to interact with the human mind.

The utility of a pair of gloves is to keep the hands warm or protected.

The utility of presenting information is to enable the person to perform a task better. But just like the gloves what is being claimed is the structure outside the human mind.

Night Writer,

Sorry but no.

marty’s qualm has nothing to do with “structure,” and instead seeks to cleave one statutory category from all of the others (method or process, which need not affirmatively claim structure).

As I had long ago noted to the late Ned Heller, the statutory categories (as provided explicitly by Congress), do NOT provide that the method/process category is any type of subset of the hard goods categories — and it would be legal error to so consider them.

But is the menu on your smart TV actually a structure, no matter how clever and pleasing ?

The method of generating the method is a process. A computer configured to generate the menu is a machine. What’s your point?

The realm of the human mind is where the patent system should not trespass, and when utility happens within a human mind

You do realize that claims do not have to recite “utility”? Utility has always been a very low bar. Regardless, almost all “utility” happens in the human mind. The human mind decides what is useful or not. Some people want faster. Some people want more efficient. Does a faster car not provide a useful result because some people don’t want faster cars?

The utility of an accurate position reading is the same for all non-human minds.

???

One is potentially justiciable, one surely is not.

Meaningless distinctions whatever they happen to be. Is the thing sought to be patented of the type that we, as a society, want more of it? If the answer to that question is yes, then it should be patentable (absent the FEW exceptions I mentioned earlier). It is simple to apply this test. This test is consistent with the Constitution. And it is consistent with the original intent of 35 USC 101.