by Dennis Crouch

One of the ambiguities with contemporary claim construction is how courts deal with loosely implied limitations from the specification. These do not rise to the level of ‘disclaimer’ but we’re never entirely sure whether the specification-forward approach of Phillips v. AWH will have traction. The courts tend to strongly oppose importing limitations into the claims absent a disclaimer, but claim-language hook can often lead to interpretative narrowing. This becomes even more interesting in situations where the patentee is using a coined term but without an express definition of scope. In those instances it seems appropriate to read more into the the specification — but how much more?

The Federal Circuit’s decision in Malvern Panalytical Inc. v. TA Instruments-Waters LLC, No. 2022-1439 (Fed. Cir. Nov. 1, 2023) offers some guidance — and also rejects the use of prosecution history from a non-family-member application in interpreting patent claim scope.

At issue was the meaning of the term “pipette guiding mechanism” as used in a pair of patents owned by Malvern. U.S. Patent Nos. 8,827,549 and and 8,449,175. The district court limited the term to only “manual” embodiments based on statements made during prosecution of an unrelated patent. With that narrow construction, the accused automated devices clearly did not infringe — and the patentee stipulated as such. On appeal, the Federal Circuit vacated the district court’s claim construction, holding that the term was not limited to manual embodiments and that unrelated prosecution history should not have been used to construe the claims.

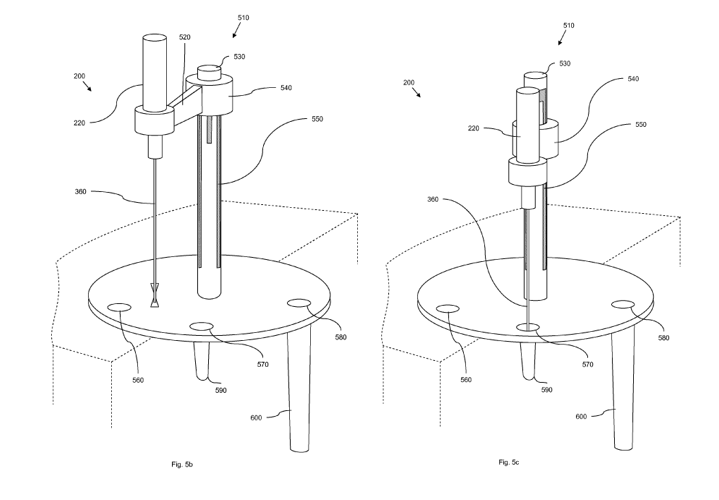

The patents relate to microcalorimeters, which are instruments used to measure the heat absorbed or released during a chemical reaction. Specifically, the patents describe an isothermal titration calorimeter (ITC) that contains several components including an automatic pipette assembly, a stirring paddle and motor, and a “pipette guiding mechanism.” The pipette guiding mechanism moves the pipette assembly between different positions, such as inserting the pipette into a sample cell for measurements or into a washing apparatus for cleaning. The key dispute was whether this pipette guiding mechanism included both manual and automatically operated embodiments. The Federal Circuit ultimately held that the plain meaning of the term encompassed both manual and automated guiding mechanisms.

District Judge Andrews (D.Del.) sided with the accused infringers in finding that the claimed “pipette guiding mechanism” should be limited only to manual operation forms. On appeal, the TA defended the judgment and raised the following arguments: (1) The specification discloses two embodiments of the guiding mechanism, both of which are operated manually and refers to a “user skills” as an aspect of operating the machine. (2) The specification goes on to describe other automated portions of the assembly, but did not do so with the guiding mechanism. (3) The term “pipette guiding mechanism” is a coined term without a plain meaning, so it can’t be broader than the embodiments in the specification. (4) that the patentee’s provided evidence that a product guide being distributed “included” the “relevant features” of their claimed invention. That product guide only described manual operation. (5) Finally, during prosecution of a separate non-family-member patent (US9103782), the patentee had argued that it was describing a ‘purely manual guiding system’ as an attempt to avoid prior art from an automated reference. Although perhaps not a complete disclaimer, TA argued that these factors come together to narrowly construe the claim to cover only manual guiding mechanisms. The Federal Circuit dismantled these arguments individually.

Claim Construction Analysis

The Federal Circuit began its analysis by looking to the plain and ordinary meaning of “pipette guiding mechanism” as would be understood by a person of ordinary skill in the art. The court found that the plain meaning encompassed both manual and automatic guiding mechanisms. This was based on examining the individual words in the claim term, as well as the overall context provided by the claims and specification. The court found no clear disavowal or redefinition in the specification or the arguments made during prosecution and so gave the claims their full ordinary meaning.

As to the coined-term argument, the court found that even coined terms can have a discernible plain and ordinary meaning based on the intrinsic evidence of the patent. There is some tension among the cases on this issue. Compare Indacon, Inc. v. Facebook, Inc., 824 F.3d 1352, 1357–58 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (coined terms without a plain and ordinary meaning in the art can be limited more readily by prosecution statements) with Littelfuse, Inc. v. Mersen USA EP Corp., 29 F.4th 1376, 1381 (Fed. Cir. 2022) (“[T]he district court was correct in seeking to give meaning to the term ‘fastening stem’ by looking to the meaning of the words ‘fastening’ and ‘stem’ as used in the patent.”). The appellate panel first noted that the doctrine is “sparingly applied” and, as here, the patent uses the individual words “pipette” “guiding” and “mechanism” in a manner that can be readily understood and does not suggest a manual limitation. Rather, “the plain and ordinary meaning of ‘pipette guiding mechanism’ is a mechanism that guides a pipette, which can be either manual or automatic.”

In this case, the claims lack a textual hook for a manual requirement and the court found no “clear and unmistakable” disavowal. As such, the proper construction is the full scope.

Use of Unrelated Prosecution History

A significant aspect of the Federal Circuit’s decision was rejecting the district court’s reliance on prosecution history from a non-family member patent to construe the claims. Although not an official ‘family member,’ the parallel application had a shared assignee, was being prosecuted by the same law firm, and and also covered a pipetting system. In that non-family-member case, the patentee had distinguished its invention from the prior art by arguing that its guiding mechanism operated manually rather than automatically. The district court treated the statements as admissions limiting “pipette guiding mechanism” to manual embodiments. That office action rejection was then submitted to the PTO in these cases as part of an IDS.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit rejected the district court analysis, holding that statements in an “unrelated” application do not guide meaning or serve as a disclaimer and further that submission of the OA in an IDS is insufficient to incorporate those statements for purposes of construing the claims at issue.

Although this answer here is probably correct, it makes me uncomfortable because it allows patentees to tell different stories in different cases. Here, the cases were being handled by different examiners in different art units — it might be a different story though if the same examiner was looking through all the similar but “unrelated” cases.

Although the logic of this case all seems clear from hindsight, I continue to be concerned that this situation offers lots of wiggle room for each side to push for advantage — akin to a nose of wax.

I have to seriously question the above statement: “the specification-forward approach of Phillips v. AWH.” That en banc case is the controlling law on this claim scope subject, but the actual decision was: “..we conclude that a person of skill in the art would not interpret the disclosure and claims of the ‘798 patent to mean that a structure extending inward from one of the wall faces is a “baffle” if it is at an acute or obtuse angle, but is not a “baffle” if it is disposed at a right angle.” That is, finding broad literal claim reading scope, even though the [reversed] district court had said that all the spec examples were angled [and had narrowed its claim reading accordingly].

Paul, I regret that to me your point is not clear. Claim construction is a matter of law so the court of appeal can take a view different from that of the DC. Or are you saying that what the PHOSITA regards a baffle is a matter of fact, not law, a matter determined by the DC, whereby it was not open to the appeal court to re-define the term “baffle”?

But apart from all that, I don’t see why any of this conflicts with a “specification forward” approach to claim construction.

From outside the jurisdiction, I read this case report with fascination. I mean, patent specifications are to be read by one skilled in the art, so what part of “pipette guiding mechanism” does such a reader not understand, immediately, without any need to turn for help to any other text than that of the claim alone?

Invocation in claim construction of the “prosecution history” strikes me as a brilliant wheeze to inject a huge multiplication factor into the cost and uncertainty of litigating a patent in the USA. Other jurisdictions don’t do it. Could it be that it is so important in the USA because i) specialist litigators like it so much, so advocate it with all possible vigour, and ii) the non-specialist judges are not clued-up enough to stand up to the pressure, not self-confident enough to out-face the advocates and crimp it down to a more equitable and economical level?

“during prosecution of a separate non-family-member patent (US9103782), the patentee had argued that it was describing a ‘purely manual guiding system’ as an attempt to avoid prior art from an automated reference.”

And right there is where the system failed everybody because if you don’t define an obviously broad functional term like “pipette guiding mechanism” then you don’t get to play the game that the applicant played here.

“ A significant aspect of the Federal Circuit’s decision was rejecting the district court’s reliance on prosecution history from a non-family member patent to construe the claims. … Although this answer here is probably correct, it makes me uncomfortable because it allows patentees to tell different stories in different cases.”

Applicants tell different stories in different non-family co-assigned patent cases ALL THE TIME. This is a “close” case in the sense that the assertions being made are about the scope of a broad functional term in two different contexts. What should make everyone much more uncomfortable are conflicting generalized assertions about the state of the art or skill in the art where the art in question (e.g., “computing”) is identical.

To be clear, the proper course of action when the issue first came up would be for the Applicant to AMEND THE CLAIM to recite “manual” (and also to show where support is found in the specification).

My apologies for an off-topic start to this thread, but on Tuesday the Fifth Circuit decided In re Tik Tok, granting a mandamus to transfer a case from WD Tex to ND Cal. Usually we discuss occasions when the Federal Circuit grants mandamus to direct transfer from the WD Tex, but the CAFC always purports to be apply CA5 law in those cases, and there has long been reason to worry that the CA5 would have decided the matter differently. Therefore, Tuesday’s precedential CA5 decision offers some useful guidance for evaluating the CAFC’s approach to these transfer mandamus requests.

My two take-aways from the CA5 opinion are: (1) that the CA5 is at pains to emphasize that mandamus should be rare; and (2) that the focus here was on the convenience of the witnesses. It is commonly asserted around here that witnesses can testify by Zoom or phone or whatnot, so this factor should not weigh heavily in the analysis. I can see the logic of this assertion, but that really does not seem to be the way that the CA5 is looking at it (slip op. at 10-12).

Greg: “the CA5 is at pains to emphasize that mandamus should be rare”

Oh brother, this again. The rest of the legal community should be “at pains” pointing out that the morality judgment re: “should be rare” has NOTHING to do with “does the law apply here to favor mandamus”. The point is that the “rarity” of mandamus should correlate with the frequency of cases being filed in the wrong venue. Everybody knows that patentees are playing games with respect to their incorporation etc so they can file in their “preferred” venues. They don’t even hide this fact. When patentees stop playing that game, then guess what? Mandamus to transfer will be “rare” again.

See also previous discussions about inequitable conduct and eligibility where this silly “should be rare” canard has been raised before (and raised always on behalf of a growing number of culprits pushing the boundaries of the law — go figure!).

Comments are closed.