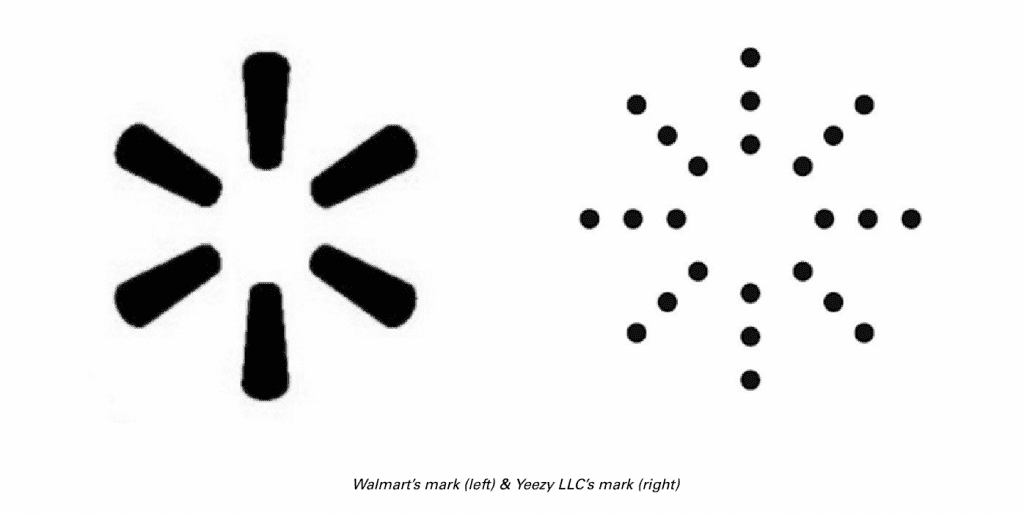

Walmart has filed a new opposition petition in the matter that it is waging against a “confusingly similar” trademark that is at the center of an application for registration filed by Kanye West’s Yeezy LLC in January 2020 for use on everything from clothing and retail store services, and musical sound recordings and streaming to hotel services and the construction of “non-metal modular homes,” among other things. According to the notice of opposition that it lodged with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (“TTAB”) in April 2020, Walmart claims that “it will be damaged by registration of [the Yeezy logo],” since it has been using a lookalike mark – “a design of six rays symmetrically centered around a circle” – since at least 2007 … on the exterior and interior signage of [its] more than 5,000 retail outlets [and] throughout its e-commerce platform.”

On the heels of initiating the opposition proceeding in an attempt to block the registration of a stylized sun rays graphic filed by Yeezy, an Interlocutory Attorney for the TTAB shot down one of Bentonville, Arkansas-based Walmart’s claims in an order dated September 3, in which she asserted that the retail giant’s Deception/False Designation of Origin pleading – which it also describes as “False Suggestion of a Connection” – is insufficient.

Specifically, TTAB Interlocutory Attorney Mary Catherine Faint states that in order to make a viable False Suggestion of a Connection claim under Trademark Act § 2(a), the opposing party (Walmart, here) must assert that “the applicant’s mark falsely suggests a connection with the opposer’s persona, points uniquely to the opposer, and is of sufficient fame that a connection with the opposer would be presumed.” Walmart fails here, according to Faint, as there is “a distinction between a term being perceived as a company’s trademark and [the mark] being a company’s persona,” and Walmart does not establish that its own “Spark Design” mark is its “identity or persona.” As such, Faint struck Walmart’s Deception/False Designation of Origin claim, giving it the opportunity to re-plead it, and leaving its likelihood of confusion, dilution and lack of bona fide intent to use claims in place.

(Faint notes that “it is hard to tell what is intended by” Walmart’s Deception/False Designation of Origin pleading, which also cites “false suggestion of a connection,” as “deception may be part of a claim under Trademark Act § 2(d), while false designation of origin is a claim under § 43(a) ‘in a civil action’ and is, therefore, inapplicable to [TTAB] proceedings.”)

Fast forward to September 23, and Walmart has amended its opposition petition, replacing its Deception/False Designation of Origin claim with a claim of False Suggestion of a Connection under Trademark Act § 2(a), and alleging that its “Spark Design” trademark “is, and since its introduction in 2007 has been, widely and heavily used to identify [Walmart].” For instance, Walmart’s counsel argues that the mark “appears on all of [Walmart’s] brick-and-mortar stores, on virtually every page of [its] e-commerce web site, on virtually every shopping bag given to customers, on virtually every television and online advertisement for [Walmart], and elsewhere.”

With such consistent and widespread use in mind, Orrick’s Mark Puzella asserts on Walmart’s behalf that the mark “has become synonymous” with Walmart. And as a result, “[C]onsumers and others are highly likely to recognize that the Walmart mark points uniquely and unmistakably to [Walmart].”

As for Yeezy’s mark, Walmart claims that it is “a close approximation of [Walmart’s] logo, which had been in wide use long prior to [Yeezy’s] filing date,” as both parties’ “designs incorporate lines of equal length radiating out from the center to resemble a spark or sunburst.” In light of such similarly, and given “the fame and reputation of [Walmart’s] mark (and the overall renown of [the retailer] as an institution),” Walmart argues that when “the Yeezy logo used with its applied-for goods and services (which are highly similar or otherwise related to those claimed by [Walmart’s] mark),” a connection between Walmart and Yeezy “would be presumed” when no such connection exists.

Against this background, Walmart claims that the Yeezy logo “would falsely suggest a connection with [Walmart], to [Walmart’s] detriment,” and thus, registration of the mark should be denied.

No Chance of Confusion

Walmart’s amended pleading comes a few months after Yeezy responded to the opposition, questioning the validity of the rights that Walmart claims that it has in the “Spark Design” mark and the “overreaching allegations” that the retail titan made in its initial opposition in an “attempt to extend its ‘Spark Design’ well beyond its federal and common law trademark rights.”

In its June 29 answer, Yeezy claimed that Walmart’s initial opposition fails on a few fronts. Primarily, the rapper-slash-designer’s counsel argued that Walmart “certainly knows, as does the consuming public, that the last thing [Yeezy] wants to do is associate itself with [Walmart],” something that was made even clearer with Yeezy and West’s filing of the unfair competition lawsuit against Walmart in connection with the sale of copycat – and “subpar quality” – Foam Runner footwear. In this vein, Walmart’s allegations that Yeezy is aiming “to mislead consumers into mistakenly believing that the parties are associated or that [Yeezy’s] goods and services emanate from [Walmart are], simply put, absurd,” counsel for Yeezy stated. Ultimately, Yeezy argued that Walmart is not actually going to be damaged by the registration of the Yeezy logo in large part because the two marks are different, and consumers are not likely to be confused.

In addition to denying the bulk of the claims that Walmart made in its initial opposition, Yeezy set out a number of affirmative defenses, arguing, among other things, that Walmart “inexplicably relies upon two cancelled trademark registrations” – including one that Walmart claims is “incontestable and provide[s] prima facie and conclusive evidence of [its] ownership and exclusive rights to use [the Spark Design] mark in commerce” – and “one abandoned trademark application as the basis for its claims,” which it cannot use as the basis for its action.

Faint struck two of those affirmative defenses in her September 3 order, stating that Yeezy’s first affirmative defenses – in which it claims that two cancelled trademark registrations and one abandoned trademark application cited by Walmart in its initial opposition “may not be relied upon to support any claims asserted by [Walmart], and they should be stricken from the opposition” – and its fourth defense – in which Yeezy argues that Walmart “inadequately pled a claim under Section 2(a) of the Lanham Act” – are not “true affirmative defenses because they relate to an assertion of the insufficiency of the pleading of [Walmart’s] claims rather than a statement of a defense to a properly pleaded claim.”

The Famous Parties

Interestingly, counsel for both parties (rightfully) argue in their respective filings that their clients are wildly well-known. 59-year-old Walmart points to the fact that it has “more than 5,000 retail outlets,” its e-commerce site “has the second largest e-commerce market share in the United States,” and it has run “nationwide television commercials, including commercials aired during the Super Bowl.” Meanwhile, counsel for Yeezy asserts that its founder Kanye West is far from an unknown figure, and in reality, is “internationally famous.”

Yet, the two parties wield these assertions in different ways, with Walmart arguing that it, and presumably, its “Spark Design” mark, are so famous that the mark is entitled to a broader scope of protection against third party uses of similar marks. Therefore, Walmart essentially contends that nearly any lookalike mark used on similar goods/services will automatically bring to mind an association with it in the minds of consumers. On the other hand, Yeezy asserts that “if anything, the opposite is true,” and that because West is so famous in his own right and the Yeezy logo “is closely associated with [him],” that consumers are likely to associate with mark with Yeezy, thereby, seemingly enabling the two companies’ marks to co-exist in the market without the risk of confusion.

As of now, it is unclear (at least to me) whether consumers actually link the sun ray mark with Yeezy (or West). I, for one, have not seen it used in any widespread capacity by Yeezy or West, and it is worth noting that the application for registration for the Yeezy logo was filed in an intent to use basis, and so, a specimen showing actual use was not included. This back-and-forth, may of course, change that to some extent, given that the two parties’ sun ray marks have been plastered all over the media in connection with the opposition.