Reframing The Legal Landscape: A Petition For Inclusivity And Linguistic Transformation

The language choices we make can greatly affect our perception of a person or group.

In a recent petition to the American Bar Association, I and a group of like-minded individuals called for a fundamental shift in language within the legal profession, urging the cessation of the term “nonlawyer.” This initiative sparks a crucial conversation about inclusivity and professional identity within legal ecosystems. As part of the conversation on LinkedIn about this effort, Sarah Glassmeyer, a law librarian who now works as director of data curation at Legaltech Hub, wrote about why she supports finding a term other than “nonlawyer” and used historical backgrounds of taxonomies to illustrate her thoughts.

In a recent petition to the American Bar Association, I and a group of like-minded individuals called for a fundamental shift in language within the legal profession, urging the cessation of the term “nonlawyer.” This initiative sparks a crucial conversation about inclusivity and professional identity within legal ecosystems. As part of the conversation on LinkedIn about this effort, Sarah Glassmeyer, a law librarian who now works as director of data curation at Legaltech Hub, wrote about why she supports finding a term other than “nonlawyer” and used historical backgrounds of taxonomies to illustrate her thoughts.

In this interview, I explore the depths of this linguistic transformation with Sarah. Her insights illuminate the significance of language in shaping perceptions as well as the broader implications for collaboration and the delivery of legal services. Join us as we explore the power of words and the potential for transformative change within the legal community.

Olga V. Mack: You mentioned the evolution of classification systems like the Library of Congress subject headings. Can you provide more examples where changing the language or taxonomy significantly impacted the perception or treatment of a group or concept within the legal field or beyond?

Law Firms Now Have A Choice In Their Document Comparison Software

Sarah Glassmeyer: Absolutely! First of all, I’ve spent a significant portion of my life working with it, but for those of you new to thinking about official classification systems, there’s a couple of baseline things to understand: (1) The world is filled with classification systems. They include everything from the ways libraries organize information, to the West Key Number system, to the filters Amazon.com puts on their website to help you narrow down a purchase and thousands of things in between, with various levels of official importance. (2) Any time a human creates something, their worldview is baked into the end product. Sometimes these biases are good, sometimes they’re bad, and sometimes they are relatively neutral. (3) With classification systems, some of the ways these biases appear can be either in language choices (such as the names we call things) or how we connect terms together. (4) For a classification system to be effective, the creators and users need to review and modify to make sure the language choices accurately reflect the time and to eliminate bias.

Some people will try to wave off a concern about language choices as conceding to “hurt feelings” or being “woke” or “politically correct.” But the language choices we make can greatly affect our perception of a person or group. For example, the Library of Congress used to have subheadings of “Jewish criminality” and “Negro criminality” but not for all ethnic groups. That implied that maybe those groups have higher than average rates of criminality.

Another example and one language choice I’ve been working on personally is saying “enslaved person” instead of “slave.” Calling someone a “slave” removes their humanity. By saying “enslaved person,” the reader/listener is reminded that the discussed individual is a person placed in a circumstance, but it’s not their defining characteristic. Along that same line, language choices can normalize things that should never be normalized. For example, the LOC used “The Jewish Question” as a blanket term for things we would now call antisemitism.

Now those are all really horrific examples. I am not equating the conversation about what to call legal professionals with the Holocaust or slavery. I’m just saying how we use words and what we call people affects more than the feelings of those being called a certain name.

Sponsored

How Transactional Lawyers Can Better Serve (And Maintain) Their Clients

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Law Firms Now Have A Choice In Their Document Comparison Software

Generative AI In Legal Work — What’s Fact And What’s Fiction?

Olga V. Mack: Could you elaborate on how the term “nonlawyer” specifically contributes to the “othering” of individuals within the legal profession, and why you believe changing this term is a crucial step towards inclusivity?

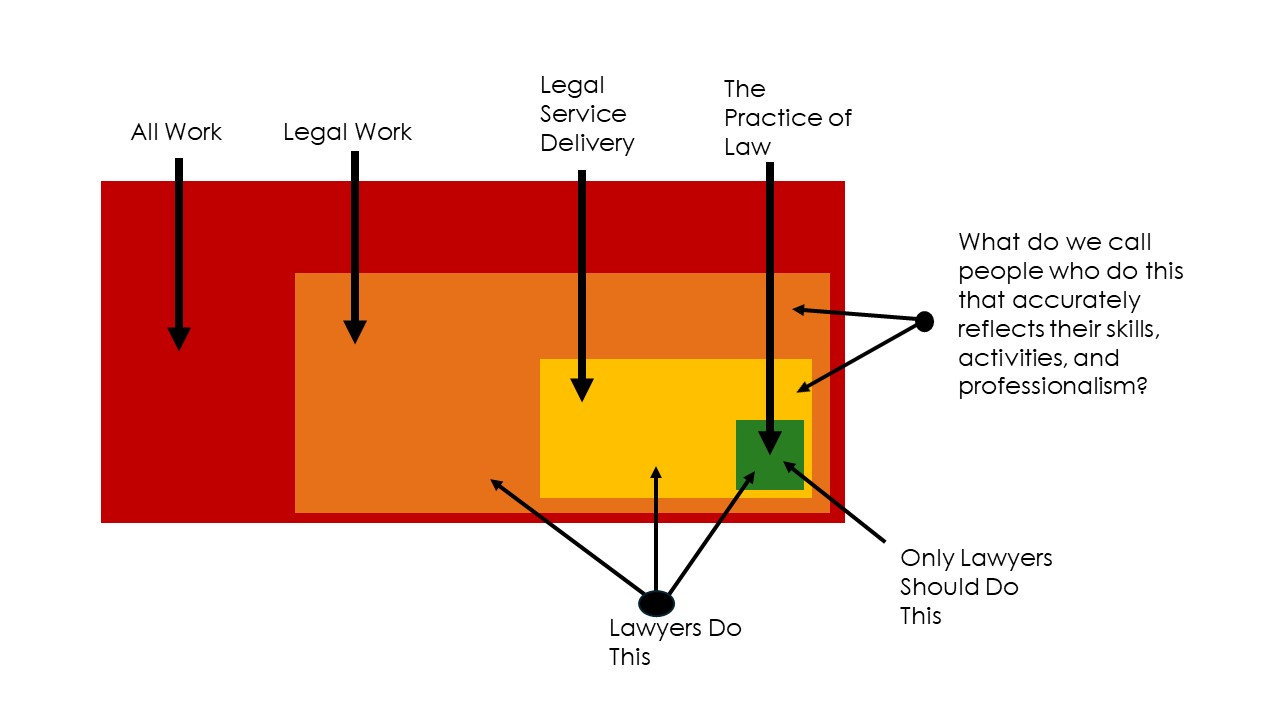

Sarah Glassmeyer: By dividing the world up into lawyers and nonlawyers, there’s an implication that there’s only “legal work” and “nonlegal work” and only legal work is performed by lawyers. However, there are many activities that could properly be defined as “legal work” that are not “the practice of law.” I’m thinking of the activities of law librarians, paralegals, legal ops departments, legal project managers, [and] legal technologists, to name a few. I think by recognizing that the people who perform this work are also professionals and also have often received extensive education and training to perform it, it recognizes and perhaps will illuminate for others what they are capable of and how they contribute to an organization’s or matter’s success. It’s moving from “lawyers and everyone else” to “here are all the people who participate in this professional sphere.”

Olga V. Mack: Have you considered or can you suggest alternative terms that could be used to describe individuals who contribute to the legal field without being licensed attorneys, which might better acknowledge their roles and expertise?

Sarah Glassmeyer: I tend to use, depending on the role, legal service providers or legal professional. And, along with that, either legal service delivery or legal work. I want to be clear — I’m not in favor of erasing all job titles or eliminating the distinctions between lawyers and everyone else who works in the legal industry. There are protections and ethical requirements for lawyers and their relationships with clients that are vital for a functioning society. It should always be made very clear — to clients, customers, and users as well as the person performing the actions — who is acting as an attorney and when these obligations kick in via the practice of law. I am simply suggesting that we use terms that fully represent the abilities and qualifications that groups of people possess when we are speaking in the aggregate.

I’m big on drawing charts and graphs to help me understand things. If it helps, here is a visualization to help clarify what I mean.

Sponsored

AI’s Impact On Law Firms Of Every Size

Generative AI In Legal Work — What’s Fact And What’s Fiction?

Olga V. Mack: In your experience, what are the main arguments against changing the term “nonlawyer,” and how do you counter these arguments?

Sarah Glassmeyer: There seems to be some fear or misunderstanding that this effort is a sneaky way to change ownership rules or that supporters of a change in terminology are trying to pretend to be something they’re not and things along that line. For what it’s worth, I went to law school and passed the bar. Also, on my LinkedIn, my headline doesn’t list my job title, my degrees, or the awards I’ve won. It says: “The World’s Okayest Legal Technologist.” I can’t speak for everyone who supports changing terminology, but I’m personally not that concerned with status or pretending to be something I’m not.

So ignoring all those arguments, because I really don’t want to make assumptions about why someone is worried about those sort of things, I can speak to the concerns about protecting clients and those that seek the services of legal professionals. Most of the FUD — Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt — used whenever any change is suggested in the legal world uses A2J as a shield. So let’s talk about it. As someone who has spent a significant amount of time in the Access to Justice world, I do worry that end users and clients may not fully understand when protections and ethical obligations kick in and when they don’t. The solution for that is to make explicit in regulatory materials and other communications what constitutes the practice of law, when these protections and obligations kick in, and who is qualified to perform what types of services and actions.

Olga V. Mack: What practical effects do you foresee in the legal profession from changing the language we use to describe legal professionals and their roles, especially regarding collaboration and the delivery of legal services?

Sarah Glassmeyer: Honestly, I think this can affect every vertical of the delivery of legal services from corporate legal ops to people that work in small law offices to Biglaw and everything in between. I’m very familiar with the A2J world so I can dive into that.

So many conversations about Access to Justice are centered around lawyers. We use statistics about representation rates in courts or who can afford an attorney to measure the “Access to Justice Gap.” Proposed solutions often take the form of increasing pro bono work or ways to make existing attorneys work more efficiently. Don’t get me wrong, those solutions are incredibly helpful and appreciated. But the umbrella of “access to justice” encompasses so much more than events that involve litigation or require the protections and skills of a licensed attorney. If we reframe the needed work as “legal services” and workers as “legal service providers,” we can invite more participants into the process of creating solutions. Again, that does not mean we remove lawyers or the much needed obligations on some types of services that only barred attorneys should provide. It just means that there’s a lot more ways to help and more people available.

Olga V. Mack: Assuming there’s agreement on moving away from the term “nonlawyer,” what steps do you believe the legal community should take to implement this change? How can we ensure that new terminology is adopted widely and effectively?

Sarah Glassmeyer: Well, for one, even if there’s not widespread agreement on changing terminology, no matter what you — yes, you, the person who is reading this — can choose to change how you yourself use language and refer to other people.

Moving out from there, people can look at their firms or organizations and see how and where the term is applied within internal documentations and policies. Are there differences in fringe or practical benefits that are applied to employees depending on how they’re classified? Do these differences … seem fair? Are they likely to encourage employee retention or professional growth or job satisfaction?

And then expanding the universe and one’s sphere of influence further, you can look at how these terms are used by local regulatory bodies. Are they inhibiting who we can consider colleagues and collaborators in the delivery of legal services? Could public needs like access to justice be increased if we change our language and potentially unintentionally limiting who can assist and how? And then maybe work to change there.

One thing I’d like to end on … for the last 10 years or so of working and writing in the areas of legal innovation and access to justice, I have been trying to frame conversations as “OK, for a minute forget about specific solution ideas like terminology changes or licensed paraprofessionals or ROBOT LAWYERS and ask yourself: ‘Are you happy with the status quo?’ ‘Do you think the legal profession is operating as effectively as possible?’ ‘Do you think everyone who needs legal help is getting it?’ And if you answer ‘no’ to any of these, congratulations, you are ready to work in innovation! Now let’s come up with some mutually acceptable ideas.”

So I guess I just encourage everyone — especially those with an immediate negative reaction to the name change — to examine their opposition and think about why they are opposed. And then, see if there’s any room for some compromise where their concerns would be addressed but the status quo is not maintained.

Olga V. Mack is a Fellow at CodeX, The Stanford Center for Legal Informatics, and a Generative AI Editor at law.MIT. Olga embraces legal innovation and had dedicated her career to improving and shaping the future of law. She is convinced that the legal profession will emerge even stronger, more resilient, and more inclusive than before by embracing technology. Olga is also an award-winning general counsel, operations professional, startup advisor, public speaker, adjunct professor, and entrepreneur. She authored Get on Board: Earning Your Ticket to a Corporate Board Seat, Fundamentals of Smart Contract Security, and Blockchain Value: Transforming Business Models, Society, and Communities. She is working on three books: Visual IQ for Lawyers (ABA 2024), The Rise of Product Lawyers: An Analytical Framework to Systematically Advise Your Clients Throughout the Product Lifecycle (Globe Law and Business 2024), and Legal Operations in the Age of AI and Data (Globe Law and Business 2024). You can follow Olga on LinkedIn and Twitter @olgavmack.

Olga V. Mack is a Fellow at CodeX, The Stanford Center for Legal Informatics, and a Generative AI Editor at law.MIT. Olga embraces legal innovation and had dedicated her career to improving and shaping the future of law. She is convinced that the legal profession will emerge even stronger, more resilient, and more inclusive than before by embracing technology. Olga is also an award-winning general counsel, operations professional, startup advisor, public speaker, adjunct professor, and entrepreneur. She authored Get on Board: Earning Your Ticket to a Corporate Board Seat, Fundamentals of Smart Contract Security, and Blockchain Value: Transforming Business Models, Society, and Communities. She is working on three books: Visual IQ for Lawyers (ABA 2024), The Rise of Product Lawyers: An Analytical Framework to Systematically Advise Your Clients Throughout the Product Lifecycle (Globe Law and Business 2024), and Legal Operations in the Age of AI and Data (Globe Law and Business 2024). You can follow Olga on LinkedIn and Twitter @olgavmack.