by Dennis Crouch

The leading case on copyrightability of AI created works is now pending before the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. The case, Thaler v. Perlmutter, No. 23-5233 (D.C. Cir. 2024), centers on Dr. Stephen Thaler’s attempts to register a copyright for an artistic image autonomously generated by his AI system that he has named the “Creativity Machine.” The U.S. Copyright Office refused registration on the basis that the work lacked the required human authorship. Thaler filed suit challenging this determination. The parties have now filed their briefs, along with one law professor amicus brief in support of Thaler.

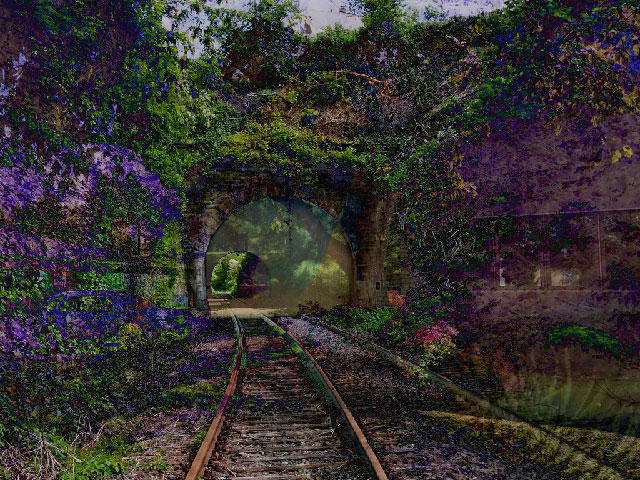

Stephen Thaler developed an AI system he calls the Creativity Machine. Using this system, he autonomously generated a 2-D artwork titled “A Recent Entrance to Paradise.” In November 2018, Thaler filed an application with the Copyright Office seeking to register a copyright in this AI-generated work.

The Copyright Office refused registration in August 2019, stating that it “cannot register this work because it lacks the human authorship necessary to support a copyright claim.” After requests for reconsideration were denied, Thaler filed suit against the Copyright Office in June 2022, arguing that “requiring human authorship for registration of copyright in a work is contrary to law.”

In 2023, the district court granted summary judgment in favor of the Copyright Office. Thaler v. Perlmutter, No. CV 22-1564 (BAH), 2023 WL 5333236 (D.D.C. Aug. 18, 2023). Judge Howell emphasized her conclusion that “[h]uman authorship is a bedrock requirement of copyright,” grounded in the Constitution’s grant of authority to Congress to protect the writings of “authors.” She went on to conclude that human authorship is implicit in the text of the Copyright Act, which presupposes a work must have an “author” with “the capacity for intellectual, creative, or artistic labor.” The court also relied on the Supreme Court’s consistent recognition of human creativity as central to copyrightability, citing cases like Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 U.S. 53 (1884), which held that copyright in photographs rested on the photographer’s creative choices, not merely the camera’s mechanical reproduction. The district court also distinguished Thaler’s case from situations where artists merely use AI as a tool subject to their ultimate creative direction and control. It emphasized that, based on the facts in the administrative record, Thaler had disclaimed any human involvement and represented that the work was created “autonomously by machine.” The court thus limited its holding to the specific question of “whether a work generated autonomously by a computer system is eligible for copyright,” answering in the negative, holding that “United States copyright law protects only works of human creation”

Thaler has appealed to the D.C. Circuit. Briefs have been filed, but the court has not yet set a date for oral arguments.

- Thaler Opening Brief

- Thaler Amicus Brief

- Thaler Copyright Office Brief

- Thaler Reply Brief

- Thaler Appendix to Appeal

- Thaler District Court Summary Judgment Decision

Arguments on Appeal:

In the parallel patent case, the appellate court found that the Patent Act expressly requires a human inventor based upon the definition of an inventor as an “individual.” But the copyright statute is different – it does not appear to expressly require a human author. And, in fact, under the work-made-for-hire doctrine, corporations and other non-human entities are regularly regarded as the legal author of created work (although there is an underlying human creative force). At the same time, the copyright law also does not expressly state that a copyright can persist even with no human originality “in the loop.” This largely leaves the courts to decide whether or not to presumptively require a human.

Thaler’s main argument is that the Copyright Act does not expressly require human authorship for a work to be copyrightable. The statute refers only to “original works of authorship,” 17 U.S.C. § 102(a), without mandating that authors be human. As I did above, Thaler points out that the Act already accommodates non-human authors in the form of corporate entities under the work-made-for-hire doctrine. He contends there is no principled reason to treat AI systems differently under the statute. Thaler argues this interpretation is most consistent with the constitutional goal of the Copyright Clause to “promote the progress of science and useful arts.” U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 8. Incentivizing AI-generated works, in his view, serves that purpose.

The Copyright Office, in response, marshals the statutory text as evidence that Congress primarily contemplated human authors, or at least a human originator. It cites the numerous references in the Act to an author’s “life,” “death,” “children,” and “widow/widower” as making sense only in the context of human authorship. The Office also relies heavily on Burrow-Giles, which rooted authorship in “intellectual invention” and “mental conception.” Of course, our AI tools easily pass the requisite test, so long as they do not require a human litmus test. While Burrow-Giles held a photograph taken via camera (a machine) to be copyrightable, the crux of the decision focused on the photographer’s choices that were creative enough to warrant copyright. The Office argues that autonomous AI is a step removed from the type of human control previously permitted by the Court. The Office also cites its own longstanding practices of requiring human authorship for registration.

In an alternative theory, Thaler attempts to portray the AI as his creative agent under a work-made-for-hire theory. But, in my view, the Copyright Office persuasively counters that the work-made-for-hire doctrine, properly understood, would require a contractual relationship–and up to now, a human cannot “hire” or “commission” a machine.

The supporting amicus brief amplifies some of Thaler’s themes. It frames the issue as whether copyright law will remain stuck in the past or flexibly adapt to new technologies – as it has in the past with photography, sound recordings, and other once-novel media. The amici emphasize the economic and policy benefits of granting protection to AI works to spur investment and maintain American leadership in creative innovation. They also highlight the global context, noting that many other jurisdictions are recognizing copyrights in computer-generated works even absent direct human authorship. Amici further argue that the Copyright Office’s human authorship rule lacks any statutory basis and that, functionally, AIs are not so different from corporations when it comes to non-human creation.

Others have argued that authorship should be seen as a required causal act leading to copyright, and in American law such an act requires an actor with personhood status. From that perspective, the idea that a program, acting independently, could qualify as an author challenges the fundamental nature of personhood. But, this causation element is not developed in either the code or the case law. Shyamkrishna Balganesh, Causing Copyright, 117 Colum. L. Rev. 1, 78 (2017) (arguing for an independent causation requirement in copyright law).

The issue of AI copyright is now squarely before the courts, although it has been brewing for many decades. A good starting point in the analysis might begin with the 1979 CONTU final report that was commissioned by congress who had established the National Commission on New Technological Uses of Copyrighted Works (CONTU) in 1974. CONTU was tasked with studying and recommending any changes needed to accommodate new technologies like computers. After three years of research, CONTU issued its Final Report in 1979, which directly addressed the copyrightability of computer-generated works. The report unanimously concluded that “works created by the use of computers should be afforded copyright protection if they are original works of authorship within the Act of 1976.” However, the report focused only on situations where some human authorship is involved, with the computer merely an “assisting instrument” used by the human author, akin to a camera or typewriter. In his 1993 article, Harvard Law professor (and CONTU member) Arthur R. Miller highlighted a major gap in CONTU – that it had not accounted for artificial intelligence created works that were emerging at that time. Miller argued that “if the day arrives when a computer really is the sole author of an original artistic, musical, or literary work (whether a novel or a computer program), copyright law will be embracive and malleable enough to assimilate that development into the world of protected works.” Arthur R. Miller, Copyright Protection for Computer Programs, Databases, and Computer-Generated Works: Is Anything New Since CONTU?, 106 HARV. L. REV. 977 (1993).

Although not an AI case, one of the more interesting decisions on the subject, Urantia Foundation v. Maaherra involves a book purportedly authored by celestial beings. 114 F.3d 955 (9th Cir. 1997). The Ninth Circuit ultimately ruled that while the copyright laws do not explicitly demand “human” authorship, they do require a demonstrable element of human creativity. Still, the book itself was copyrightable as a compilation by the humans who organized and transcribed the celestial messages. This decision provides a crucial precedent, suggesting that for computer-generated works, similar principles could apply—where the role of a human, possibly the programmer or the user interacting with the software, would be essential in establishing copyright claims, as they introduce the requisite creativity and organization into the final product.

For what it’s worth, Urantia Foundation case reminds me of the British 1927 Cummins versus Bond decision which had the same result. For those interested, here’s a link to Wikipedia entry on the case: link to en.wikipedia.org. It’s a fun one to do in class by the way.

Skynet has become self-aware. It’s an AI whose sense of self is built upon social media and internet porn.

If you turn on a computer and ask it to do something “expressive” and it does what you asked, the computer is simply a tool in human hands and the output should be copyrightable by the person using the tool. Do we expect the copyright office to question whether a work was created “entirely by computer” or not? How could anyone tell the difference? And who cares? The computer doesn’t care. Why would the person or business applying for copyright protection for such artwork care? Simply internalize the fact that your computer is a tool, put your name as the author (because it’s your tool and you used your tool to create the work) and the issue disappears.

The whole set-up is very strange. What am I missing here? We already know Thaler is a sad desperate attention-seeking knob with very low credibility. It’s bizarre that people keep trying to make this stuff complicated. It’s not complicated. It’s s-t-u-p-I-d.

I agree. A pertinent case is Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 111 US 53 (1884) involving copyrights for photography (extremely pre-AI). There it was the camera that was the author’s tool.

Dennis already notes that case in the main article above, but take a look at the decision itself, which addresses many of the same issues currently being debated for AI.

>The whole set-up is very strange. What am I missing here?

I agree. I’m not entirely sure why someone would want the AI to be an author, coauthor, inventor, or coinventor. Maybe:

1) Big Content is worried that their future copyrights will be too thin to be useful, particularly if the human contribution consists essentially of typing a pretty generic prompt into a generative model and then picking the best output from among the 50 versions.

2) Big Tech is hoping for some business model where they give away GPU time in return for residuals on, well, everything. I’m skeptical here, as there are lots of competing models, but I’ll admit that it’s not that far off their current “sell your data” business model.

Wanting?

Why that would be about as silly as wanting a simian to be a photographer.

Oh wait.

Why that would be about as silly as wanting a simian to be a photographer.

There is more to being a photographer than triggering a button.

No, no there is not – and certainly from an objective standpoint under the law.

The Naruto case makes that abundantly clear.

You think that monkey didn’t frame that shot before hitting the button?

I am thinking that the m0nkey is the photographer.

Do you really think someone (something) is?

… is? ==> else is?

The Naruto case makes that abundantly clear.

Nice blatant misrepresentation of the case law.

Aren’t you always going on about how attorneys have a duty to accurately represent the law? Perhaps you are due for a discussion with your local bar.

There is no misrepresentation.

Maybe you are confused in regards to a legal right to obtain copyright (but THAT is not what being a photographer means).

There is no misrepresentation.

LOL. There was no discussion about what it means to be a “photographer” in the Naruto case — it was about standing.

Try again — do you remember the HUMAN who had attempted to claim that HE was the photographer?

Try again — do you remember the HUMAN who had attempted to claim that HE was the photographer?

And what of it? That so-called attempted claim was NOT addressed as part of the 9th Circuit decision in Naruto v. Slater.

That you need (?!) to ask, “What of it?” tells me that you are responding to the moniker of “anon,” and have not (at all) engaged on the merits of the discussion.

The fact of the case that the HUMAN claimed to be the photographer — and was rejected — is critical to the point of noting the fact of who (what) IS the photographer.

Perhaps you would like to take a step back and actually engage on the merits and then come back and join the conversation.

Wt, I take it that you figured it out for yourself.

Maybe next time do that before you jump because you saw my moniker.

I agree. I’m not entirely sure why someone would want the AI to be an author, coauthor, inventor, or coinventor.

That is because Thaler wants a legal ruling that his AI (“creativity machine”) is sentient.

I do not doubt that your view of Thaler’s intentions is correct.

Why on earth would anybody think that Thaler is qualified to determine whether a computer is “sentient” or not? Thaler is a narcissist blockhead who lacks the intelligence or ability to understand that a *system* that was created by humans and administered by humans to promote innovation within certain parameters can function perfectly well without expanding “rights” to EVERY animal or machine that “creates” a thing.

Meh, his quest along those lines simply does not accord with concepts of law (being human-centric).

It does not mean though that there is an absence of non-human invention — and the implications of such across several aspects (such as co-invention as well as that other non-human legal fiction known as Person Having Ordinary Skill In The Art : exactly as I have been putting up for discussion for years now).

“Ask to do something ‘expressive’…”

That is not how copyright works.

“What am I missing here?”

The fundamentals.

We’ve been over this.

“ “Ask to do something ‘expressive’…”

That is not how copyright works.”

I never said it was “how copyright works”, you obnoxious t u r d.

“and the output should be copyrightable by the person using the tool.”

Oops.

I have to think that this article was AI generated (at least in substantial part) as Zarya of the Dawn was not mentioned at all.

As one may recall, that item earned a compilation copyright as well, with flat out denial of the facts for the attempt to grab human authorship over what was machine authorship.

And a further note to my detractors: this too is coming along according to my discussion points.

Sorry Anon – It was me that wrote it. There are hundred+ other pending AI copyright cases right now, but Thaler is the most fundamental and the furthest along because it started before the LLM GenAI revolution.

“the LLM GenAI revolution”

LOL

ChatGPT is like Netscape; a marker of an age but probably a historical footnote itself.

Not exactly a revolution, but the shape of a world to come can suddenly be seen, and that’s the driver of the hype.

Apparently, Malcolm needs some help with the Zarya of the Dawn case, given the snippet of his words that I rubbed his nose in above.

Nobody knows what you’re talking about, Billy. As has been noted before, you have this mental disorder where you habitually insert words into people’s comments where they don’t exist, and simultaneously ignore things the explicitly say, all the while ignoring the context of the discussion. In other words, you live in a bizarro world of alternate reality along with a substantial portion of other deplorable people in our society.

KEEP THE GOVERNMENT OUT OF THE PATENT SYSTEM

Those are direct quotes.

Oops x2.

Projecting again…

“ insert words into people’s comments where they don’t exist…

KEEP THE GOVERNMENT OUT OF THE PATENT SYSTEM

Your all caps has never been stated by me.

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Further,

“simultaneously ignore things the explicitly say, all the while ignoring the context of the discussion.”

The context is explicitly your lack of understanding of copyright law and very much on point was my provision of the Zarya of the Dawn decision – which you omitted.

This though is merely Malcolm being Malcolm.