by Dennis Crouch

The Federal Circuit’s recent decision in Virtek Vision International ULC v. Assembly Guidance Systems, Inc. focuses on the motivation to combine aspect of the obviousness analysis. The court’s ruling emphasizes that the mere existence of prior art elements is not sufficient to render a claimed invention obvious; rather, there must be a clear reason or rationale for a person of ordinary skill in the art to combine those elements in the claimed manner. In the case, the IPR petitioner failed to articulate that reasoning and thus the PTAB’s obviousness finding was improper.

The Motivation to Combine:

In patent law, the “motivation to combine” doctrine plays a central role in determining whether a claimed invention is obvious under our guiding statute, 35 U.S.C. § 103. The doctrine is particularly relevant in cases involving “combination patents,” where the claimed invention consists of elements individually known in the prior art.

In patent law doctrine, we mentally construct a fictional Person Having Ordinary Skill in the Art (PHOSITA) and ask the legal question of whether the claimed invention would have been obvious to the PHOSITA. An odd trick of the approach in obviousness doctrine is that we first assume that PHOSITA would have perfect knowledge of all prior art that is analogous to the problem being addressed, even obscure or cryptically written references. By relying upon this perfect knowledge of prior art and by breaking down an invention into small enough components, it is very often true that all of the components of the claimed invention can be found somewhere in the prior art.

However, the mere fact that all the components of the invention exist in the prior art does not necessarily render the invention obvious. The key question is whether the PHOSITA, armed with this perfect knowledge of the prior art, would have had a motivation to combine those components in the specific way claimed in the patent and a reasonable expectation of success in doing so. This is where the motivation to combine doctrine comes into play. As emphasized in the Virtek Vision decision, there must be some reason or rationale that would have prompted the PHOSITA to select and combine the specific teachings from the prior art to arrive at the claimed invention.

In KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398 (2007), the Supreme Court discussed situations where a combination of prior art elements would be considered obvious:

When a work is available in one field of endeavor, design incentives and other market forces can prompt variations of it, either in the same field or a different one. If a person of ordinary skill can implement a predictable variation, § 103 likely bars its patentability. For the same reason, if a technique has been used to improve one device, and a person of ordinary skill in the art would recognize that it would improve similar devices in the same way, using the technique is obvious unless its actual application is beyond his or her skill.

The Court further explained:

[I]f a technique has been used to improve one device, and a person of ordinary skill in the art would recognize that it would improve similar devices in the same way, using the technique is obvious unless its actual application is beyond his or her skill. [A] court must ask whether the improvement is more than the predictable use of prior art elements according to their established functions.

Although these portions of KSR broadly suggest that it can be enough to simply show that the component is well known in the art, other portions of the decision declare that is insufficient: “a patent composed of several elements is not proved obvious merely by demonstrating that each of its elements was, independently, known in the prior art.” Rather, there must be a reason (or motivation) provided for a person of ordinary skill in the art to combine those elements in the claimed manner.

This evidence of motivation-to-combine is a necessary element proving a combination patent obvious, and the court justified the requirement based upon the theory of hindsight bias: “A factfinder should be aware, of course, of the distortion caused by hindsight bias and must be cautious of arguments reliant upon ex post reasoning.” The Court stated:

Often, it will be necessary for a court to look to interrelated teachings of multiple patents; the effects of demands known to the design community or present in the marketplace; and the background knowledge possessed by a person having ordinary skill in the art, all in order to determine whether there was an apparent reason to combine the known elements in the fashion claimed by the patent at issue.

Id. Thus, in addition to being derived from a prior art reference itself as was allowed under TSM, the Court indicated that evidence of a motivation to combine can come from other sources, such as:

- Interrelated teachings of multiple patents;

- Demands known to the design community or present in the marketplace; or even

- Background knowledge possessed by a person having ordinary skill in the art.

The Court further emphasized that “[t]o facilitate review, this analysis should be made explicit.” In other words, the motivation to combine must be expressly proven to a factfinder.

The Virtek Vision Dispute:

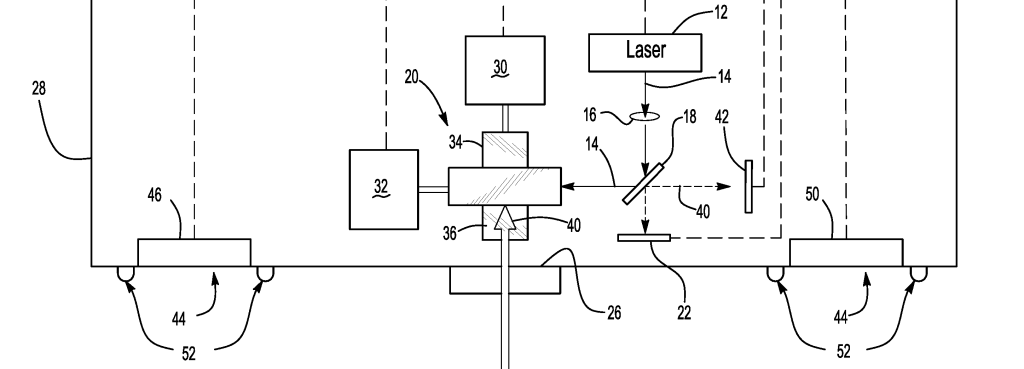

Virtek owns U.S. Patent No. 10,052,734, which discloses an improved method for aligning a laser projector with respect to a work surface using a two-step process involving a secondary light source and a laser beam. Assembly Guidance Systems, Inc. (Aligned Vision) petitioned for inter partes review (IPR) of all claims of the ‘734 patent, asserting four grounds of unpatentability based on various combinations of prior art references: Keitler, Briggs, Bridges, and ‘094 Rueb.

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) issued a split final written decision holding claims 1, 2, 5, 7, and 10–13 unpatentable based on the combinations of Keitler/Briggs (Ground 1) and Bridges/Briggs (Ground 3). However, the PTAB found that Aligned Vision failed to prove claims 3, 4, 6, 8, and 9 were unpatentable.

Regarding claim 1, the PTAB had agreed with the petitioner that the primary references (Keitler and Briggs) taught all the claim elements except for “identifying a pattern of the reflective targets on the work surface in a three dimensional coordinate system.” The Board found that Briggs disclosed the step of determining the 3D coordinates of targets, and that the claim was obvious. According to the Federal Circuit, the Board’s reasoning for a motivation to combine was simply that the components had been disclosed: “The Board reasoned this combination would have been obvious to try because Briggs discloses both 3D coordinates and angular directions.” The Board noted that the references provided “two alternative” solutions to a problem and that, under KSR this “finite number of identified predictable solutions” provide a reason to combine.

The Federal Circuit’s Analysis:

On appeal, the Federal Circuit reversed the PTAB’s unpatentability findings for claims 1, 2, 5, 7, and 10–13, holding that substantial evidence did not support the PTAB’s findings of a motivation to combine Briggs with either Keitler or Bridges. The court emphasized that “the mere fact that these possible arrangements existed in the prior art does not provide a reason that a skilled artisan would have substituted the one-camera angular direction system in Keitler and Bridges with the two-camera 3D coordinate system disclosed in Briggs.”

In looking at the evidence presented, the court found no evidence of a design need, market pressure, or finite number of predictable solutions that would have prompted a PHOSITA to combine the references as claimed. In particular, the court found no evidence presented to support the idea that there were a finite number of identified, predictable solutions in this case. At oral arguments, petitioner’s attorney explained that only two ways of performing the task were provided as evidence — but did not provide any affirmative evidence that those were the only two ways of doing so.

The court also highlighted its previous decision in Belden, which implemented a somewhat strong version of KSR — emphasizing that obviousness requires more than just showing that a POSITA could have made the combination, but also that they would have been motivated to do so:

Obviousness concerns whether a skilled artisan not only could have made but would have been motivated to make the combinations or modifications of prior art to arrive at the claimed invention.

Belden Inc. v. Berk-Tek LLC, 805 F.3d 1064, 1073 (Fed. Cir. 2015). At oral arguments, Judge Hughes noted that indeed it does seem quite technologically simple to combine the references together, but repeatedly asked about the motivation — why would someone be motivated to do so:

KSR does allow a somewhat relaxed look at obviousness. But the references have to show not just how you would combine them, but why you could combine them. And where in any of this record is that why answered?

Oral Args. at 15:14. Chief Judge Moore agreed:

You have to agree that just because a bunch of things are known in the industry [does not make the combination obvious], that would turn obviousness on its head. Hindsight would run rampant if just the mere fact of things being known was sufficient to then piece them together without that ‘why.’

Oral Args. at 21:05. Aligned Vision’s petition and the supporting declaration of its expert, Dr. Mohazzab, relied primarily on the assertion that the prior art references disclosed all the elements of the claimed invention and that these elements were “known to be used.” However, the Federal Circuit found that insufficient. The court noted that Aligned Vision’s IPR petition did not argue that the prior art articulated any reason to substitute one coordinate system for another or any advantages that would flow from doing so. Moreover, during his deposition, Dr. Mohazzab admitted that he did not provide any reason to combine the references in his expert declaration. The court concluded that the conclusory assertions in Dr. Mohazzab’s declaration and the petition’s reliance on the mere existence of the elements in the prior art did not constitute substantial evidence for finding a motivation to combine.

The Federal Circuit also rejected Aligned Vision’s attempt to introduce a new “common sense” rationale for combining the references during the IPR proceedings. The court cited its decision in Intelligent Bio-Systems, Inc. v. Illumina Cambridge Ltd., 821 F.3d 1359 (Fed. Cir. 2016), which held that a petitioner may not rely on an entirely new rationale to explain the motivation to combine in its reply and accompanying expert declaration. This principle also applies to expert depositions that take place after the service of the reply and declaration. Since Aligned Vision did not argue common sense in its petition or Dr. Mohazzab’s declaration, the court found that this new rationale could not support the PTAB’s motivation to combine findings.

= = =

I’ll note one aspect of the case appears to be that petitioner’s technical expert failed to understand the nuances of patent law and thus substantially hurt the obviousness argument. The following comes from Chief Judge Moore at oral arguments:

I have to be honest with you. I was very troubled by the expert testimony in this case. I mean, five hours, I don’t really have any sense of what a hard and fast rule ought to be for the amount of time someone spends getting prepared.

And had your expert said, oh, I didn’t have to spend a lot of time reading the three or four prior art references in the patent because I was already familiar with them. But it appears he didn’t have much familiarity with patent law, for sure, or with these patents, based on his deposition. And the idea that he spent a total of five hours coming to sign from start to finish involving research and review a document that you drafted that has 121 paragraphs and is 56 pages long, that is a deeply troubling thing to me as a starting point.

However, if his deposition he had really demonstrated a complete understanding of all of the issues that were present in his declaration, perhaps that could overcome the concern.

17 separate times, your expert suggested that he didn’t think references had to be combined. 17. He doesn’t seem to understand the difference between anticipation and obviousness. He doesn’t seem quite clearly to even understand what his own declarations said. He sure doesn’t understand the legal concepts. I don’t know what to do with that.

I’m a little horrified. I mean, I think I almost wanted to say, did you take him drinking before the deposition? What happened? Because this is a colossal collapse.

You couldn’t have walked out of that deposition feeling like, nailed that one. This was like, this is the nuclear bomb just dropped on your case, in terms of his credibility. And so I don’t know what to do with that piece. It’s really troubling.

And I’ll tell you, I look, and there’s not a lot of standards out there. We haven’t said a lot on what makes an expert reliable or credible in a Daubert sort of way, when they should be excluded under circumstances like this. I’d like your input on that. This issue was raised, and you barely addressed it in your reply brief. All you said in your reply brief is, the board decided what it should have decided, and we should follow it. You said nothing specific.

It will be interesting to see how the court moves forward with expert standards for PTAB cases.

I note the references to “task” and “solution” when pondering on whether there was at the relevant date any “motivation to combine”. How much does this help, to get to the right answer?

I suppose it is legitimate to look to the specification that supports the claim, to divine the field of endeavour of the notional POSA. How legitimate (or necessary) is it to look to the specification for elucidation what was the “task” and what was the “solution”?

For US readers it might be an uninteresting question. If so, sorry. But I’m in Europe where the specification is indeed used in that way.

It seems to me that one can only determine whether there was any motivation back then, after you have fixed what was the notional “task” occupying the mind of the imaginary POSA, back then. So, how do you fix that task? And it seems to me that the writer of the specification, writing it prior to the “obviousness date” but knowing what was the prior art, has in a First to File jurisdiction a standing advantage over those trying to prove obviousness, many years later, without the taint of hindsight reasoning.

So, how does one achieve a level playing field, between inventor and PTO, without resort, every time, to a Declaration, given even more years later, from a self-professed technical expert? How about holding inventors strictly to what they say about “task”, “problem” and “solution” in their patent application as filed?

How do you do that, in the USA?

>How about holding inventors strictly to what they say about “task”, “problem” and “solution” in their patent application as filed?

A long time ago, we would expressly list various objects of the invention. More recently, we would set up the problem solved (aka sell the invention a bit) via a background section.

The problem with both approaches was that the Fed. Circuit would often read those objects / background into the claims… so now, nobody uses objects and many practitioners skip the background section altogether.

I know Europe likes that kind of thing, so I often include the same content in the detailed description. But it’s now kinda a needle hidden in a haystack of patentese.

The very real presence of patent profanity.

Judge Moore has come a long way since Agrizap v. Woodstream. There she reversed the district court, granted JMOL of obviousness, invalidated the patent — all in view of a three reference combination and secondary indicia of non-obviousness including the commercial success of the Rat Zapper, copying by Woodstream, and a long felt need in the market for electronic rat traps, not to mention a presumption that the jury found that the objective evidence of non-obviousness favored Agrizap.

“ a long felt need in the market for electronic rat traps”

Oh, right, this is that famous case from 1912.

No, Judge Moore wasn’t alive in 1912.

Right. And there was no “long felt need for electric rat traps” when Judge Moore crushed that cr @ p patent.

I can certainly see a long felt and unsatisfied need for electric shock treatment of anti-patent vermin in the immediate vicinity.

“In patent law doctrine, we mentally construct a fictional Person Having Ordinary Skill in the Art (PHOSITA) and ask the legal question of whether the claimed invention would have been obvious to the PHOSITA.”

The thing of it is that there seems to be no agreed upon manner of determining the level of ordinary skill in the art at the Examiner level, the PTAB level, or the Federal Court level. It’s just pulled out of thin air.

… Graham Factors.

Yes- PHOSITA should be construed, just like the words in a claim, as a threshold matter of law. This exercise would help to locate the novelty in the invention, especially in inventions touching on multiple art areas or turn on functional claims.

“Novelty in the invention.”

Claims are taken as a whole.

Just in case your counsel told you, but you have forgotten.

mmmm hmmmm suuuureeee

Every examiner & judge & prosecutor & patentee & accused infringer considers each and every element of and every word of every claim as having exactly the same effect, all of them the “invention”, none more or less important than any other.

Everyone knows that.

Nice strawman – did you borrow that from Malcolm?

I don’t see how this decision can be reconciled with KSR’s admonitions that an invention is obvious if it is the mere “simple substitution of one known element for another” and “if a technique has been used to improve one device, and a POSA would recognize that it would improve similar devices in the same way, using the technique is obvious unless its actual application is beyond his or her skill.” Those are exactly this case, and the Federal Circuit essentially overwrote these rationales by insisting that there still must be a sufficient “motivation” for swapping one element for another.

Much of KSR is dedicated to repudiating the notion that POSAs cannot find any change obvious unless there’s a clear reason to do it. The clear thrust of the opinion is that combining known elements where each element performs the same function as before is obvious unless there was something unpredictable about their combination–a nearly-200-year-old truism of patent law. Some Federal Circuit judges seem to be trying very hard to repackage KSR as merely widening the scope of where the “motivation” can come from–in theory market forces, design needs, etc., but I doubt the CAFC has often, if ever, credited such a theory.

Unfortunately Dennis today indulges some common distortions of KSR: (1) “a patent composed of several elements is not proved obvious merely by demonstrating that each of its elements was, independently, known in the prior art.” No one would dispute this; you can’t pull teachings from wildly different arts and try to mash them together without regard for the feasibility of their combination. And the next sentence is “Although common sense directs one to look with care at a patent application that claims as innovation the combination of two known devices according to their established functions, it *CAN* be important to identify a reason that would have prompted a person of ordinary skill in the relevant field to combine the elements in the way the claimed new invention does.” (emphasis mine).

(2) What KSR actually said about hindsight bias: “The Court of Appeals, finally, drew the wrong conclusion from the risk of courts and patent examiners falling prey to hindsight bias. A factfinder should be aware, of course, of the distortion caused by hindsight bias and must be cautious of arguments reliant upon ex post reasoning. Rigid preventative rules that deny factfinders recourse to common sense, however, are neither necessary under our case law nor consistent with it.”

Even taking the Federal Circuit’s view of 103 as correct, it’s absurd to claim a POSA wouldn’t “combine these references”–as the CAFC would put it. The two references are both directed to the exact same art that the claimed invention is–laser projection systems for calibrating the position of objects in manufacturing processes. I’m not sure why the Federal Circuit didn’t read the cited paragraph of Briggs, but it states the reason for using the two-camera, two-light source method explicitly: to triangulate the 3D coordinates of any point in the camera’s view. That’s the principle of the claimed invention. I have no idea how it can be a patentable invention to apply that principle to prior art devices in the exact same art for the exact same purpose.

“ I have no idea how it can be a patentable invention to apply that principle to prior art devices in the exact same art for the exact same purpose.”

It’s not. Another defendant with a competent expert and better attorneys could shred this patent.

Much of KSR is dedicated to repudiating the notion that POSAs cannot find any change obvious unless there’s a clear reason to do it.

The Supreme Court stated “rejections on obviousness grounds cannot be sustained by merely conclusory statements; instead there must be some articulated reasoning with some rational underpinning to support the legal conclusion of obviousness.”

The key language is articulated reasoning with some rational underpinning. As stated by the Federal Circuit, “The mere fact that these possible arrangements existed in the prior art does not provide a reason that a skilled artisan would have substituted the one-camera angular direction system in Keitler and Bridges with the two-camera 3D coordinate system disclosed in Briggs.” Merely the possibility of a substitution is not enough. As also noted by the Federal Circuit, “[t]he petition does not argue Briggs articulates any reason to substitute one for another or any advantages that would flow from doing so.” The Federal Circuit concluded: “It does not suffice to simply be known. A reason for combining must exist.”

As for what the USPTO actually did (or didn’t do), I do not know. The Federal Circuit likes to pick and choose the facts they rely upon based upon what the decide upon.

Even taking the Federal Circuit’s view of 103 as correct, it’s absurd to claim a POSA wouldn’t “combine these references”–as the CAFC would put it.

That is a straw man argument. The Federal Circuit didn’t write that a person of ordinary skill in the art wouldn’t combine these references. Rather, the only two statements using your quoted language were:

“Nor does Dr. Mohazzab, Aligned Vision’s expert, articulate any reason why a skilled artisan would combine these references. … Moreover, he stated eleven times that he did not provide any reason to combine the references in his expert declaration. ” The burden of proof rests with the challenger of the patent. What the Federal Circuit was saying is that the challenger’s expert did not present a reason to combine the references. With that articulated reasoning missing, the Federal Circuit was going to reverse the Board.

I’m not sure why the Federal Circuit didn’t read the cited paragraph of Briggs, but it states the reason for using the two-camera, two-light source method explicitly: to triangulate the 3D coordinates of any point in the camera’s view.

Because it isn’t up to the Federal Circuit to make findings of fact. Its not their job to bolster an incomplete record. Maybe they’ll do it from time to time when they are so inclined, but the standard of review at the Federal Circuit does not involve a de novo review of the facts — only the legal determination of obviousness.

1) The “articulated reasoning with some rational underpinning” is that two techniques were disclosed in a prior art reference in the exact same field, and there’s no dispute a POSA *could* implement this technique in the way claimed. “If a person of ordinary skill can implement a predictable variation, §103 likely bars its patentability.” The claimed invention is not an unusual way of implementing the technique disclosed in Briggs. It’s implementing that technique in the exact way it was disclosed and is thus a “predictable use of prior art elements according to their established functions”. That is all the reasoning KSR demanded. To put in the CAFC’s language, “it does [] suffice to meet the [obviousness] requirement to recognize that two alternative arrangements . . . were both known in the art” unless there was something unpredictable about their combination.

2) It’s not a strawman. CAFC said “KSR did not do away with the

requirement that there must exist a motivation to combine various prior art references in order for a skilled artisan to make the claimed invention” and “In short, this case involves nothing other than an assertion that because two coordinate systems were disclosed in a prior art reference and were therefore “known,” that satisfies the motivation to combine analysis. That is an error as a matter of law. It does not

suffice to simply be known. A reason for combining must exist.” That’s clearly the rationale for the decision.

3) The whole decision is premised on reversing a finding of fact, standard of review notwithstanding. And the FWD quoted that whole paragraph of Briggs on 19-20, so the Federal Circuit is on the hook, in theory, for having read that part.

An easier fact pattern for discussion purposes is all the obvious inventions that improve “automation” of a task by virtue of an additional “sensor” or “sensors” that … sense stuff! But because nobody in The Journal of This Very Specific Task ever explained in print why four sensors instead of two would be useful, there is therefore no motivation to add those extra two sensors.

As to “reason to combine”, however banal that might be, I wonder whether the one which we often see in EPO exam reports would provide in the USA any traction at all. As we all know, at the EPO one toggles between technical features recited in the claim, and the technical effects they deliver, to discern what was the task of the notional skilled person.

In a case where the new combination of technical features recited in the claim delivers nothing more than the POSA would expect and the Applicant has no evidence that the claimed solution delivers anything more than a “mere alternative” to the known solution, then the “reason to combine” is the one, trivial for the POSA, of simply finding an alternative construction. It is theoretically possible perhaps, but in practice beyond imagination, that the POSA contemplating any given problem has no motivation to offer an alternative to the known solution. Finding alternatives is what skilled people do, isn’t it?

So it is, that in Europe the reason “looking for an alternative” gets the Examiner (or petitioner for revocation) home. Might it also do so, in the USA, I wonder.

Is anyone aware of a source (case, rule or guidance) that provides an objective definition of “articulated reasoning with some rational underpinning” against which Examiner’s rational could be measured?

As that test is currently applied by most US examiners, it is impossible NOT to always be satisfied. In the view of most Examiners, all it seems to require is a generic statement that “a POSITA would be motivated to combine X with Y because it would improve [insert random function of the invention as stated in the specification] of the device.”

A lot of time and client money is spent and wasted on addressing fictional rationales of this kind.

I’d define it as “a coherent explanation supported by evidence or at least logic.”

I think it’s mostly filler tbh. KSR was a Kennedy opinion after all.

I think it’s mostly filler tbh.

Of course you do. Without an articulated reasoning supported by a rational underpinning then every combination of old elements (which is the vast majority of inventions) is obvious absent some indicia of nonobviousness, which is extremely difficult to show these days.

The problem I have with many comments on this blog is that they don’t think through the consequences of what they are arguing. They apply their preferred ‘legal logic’ to a particular set of facts so as to obtain a particular desired result and declare “voila … this is how the law should be applied.” However, they do so without contemplating how their preferred ‘legal logic’ applies to other sets of facts — not realizing that in many instances their preferred ‘legal logic’ makes almost everything unpatentable.

I suspect there are some here who would welcome almost everything being unpatentable, but if that’s their end goal, I would hope they would be more upfront about that goal.

I was being charitable and criticizing this phrase of KSR for being mostly nonce words with no real meaning, a la “reasonable” (which is true of many opinions written by older judges, a habit that is mercifully starting to wane with newer judges). This is true of a lot of SCOTUS patent opinions, where their impulses are generally good, but the execution is poor and their knowledge of patent law superficial. You took this out of context to suggest I believe all combinations are obvious, which I do not. My previous comments explain my views; basically, it is obvious to combine A+B and C where each is performing the same function as before; there are no implementation difficulties in combining them; they aren’t being pulled from widely disparate arts; and there are no unexpected results.

I have that view because it is the clear thrust of 200 years of Supreme Court patent jurisprudence, and because my best guess, based upon theoretical and empirical research and my own perception having practiced in this field, is that the present level of patenting is too high partly as a result of overly lax inventiveness standards. I’m open to changing my views if presented with good evidence.

Ultimately, the point of the patent system is to maximize innovation, and I believe legal standards should be revised as needed to accomplish that goal. If that means we need to have 10 million patents in circulation, rather than the present 6 million, then I’m fine with that. But I very much doubt that you would be fine with reducing the number of patents to 1 million if that were the innovation-maximizing number. So who is the one not “think[ing] through the consequences of what they are arguing” here?

“their impulses are generally good, but the execution is poor and their knowledge of patent law superficial.”

Case in point: Kyle.

Wt – funny that – where we agree, it is generally on the topic of patent law.

As here.

Kyle is a litigator – he speaks without understanding.

This “articulated reasoning with some rational underpinning” language is among the most foolish and destructive things the Supreme Court has never said in a patent law case. Because it wasn’t hardly supposed to mean anything, certainly not anything particularly anti-patentability, but it has been misinterpreted, first by Board decisions and now gradually, and worse, by the Federal Circuit, in a ridiculously anti-patent way.

This phrase was NOT supposed to state any standard for any trial court or tribunal to use to DETERMINE WHETHER there is obviousness. Not even close.

How do I know that this was not supposed to be the standard for determining whether a claimed invention is obvious? Simple. Just use a little bit of your great big imagination to flip it around. Under what circumstances will a theory of NONobviousness by the PATENT OWNER be accepted by a tribunal just because the patent owner offers the tribunal “articulated reasoning with some rational underpinning” in favor of its patentability-supporting theory?

That’s right. There is no conceivable situation under which that would EVER be the necessary threshold such that the tribunal, at trial, would accept the patent owner’s theory and REJECT a theory of obviousness. You know why? Because no one has ever thought of such a laughable thing, and for good reason: this is simply not plausible as a threshold for WINNING at trial. Use a little bit more of your big imagination. How would that work?

———————-

PATENT OWNER: Your honors, my patent is not obvious as a matter of law because, based on all the evidence presented by me and by the petitioner challenging the patent at trial, I have presented articulated reasoning with some rational underpinning in support of my theory of nonobviousness.

PTAB: I totally agree. When I listened to you, you articulated some very plausible reasoning, and it was underpinned by some facts, and I found the connection between your reasoning and those facts to be rational. You win. On the question of law of obviousness/nonobviousness, I hold that this claim is not shown to be obvious.

PETITIONER: Say what?!?!?! ! ! ? ?

PTAB: Huh? What’s the problem?

PETITIONER: What’s the problem?!? How about, when we presented our theory of OBVIOUSNESS, we ALSO presented you with articulated reasoning with some rational underpinning! Lots of reasoning! Lots of underpinning!! Respectfully, we believe that we presented the Board with MORE reasoning and MORE underpinning that was MORE rational!

PTAB: So? Someone told me that a nonobviousness argument has to be supported by “articulated reasoning with some rational underpinning.” This is. So I don’t see why it matters whether you also presented articulated reasoning with a rational underpinning. My understanding of what the higher court said is that that is irrelevant. No, you have to show me that either the patent owner failed to articulate reasoning, or the patent owner’s articulated reasoning wasn’t underpinned by anything rational. And you didn’t do that. You just wasted your time presenting articulating your own reasoning and trying to underpin that. You didn’t address what matters. You lose.

———————-

You see how absolutely ridiculous that notion is? (And yet… if you’ve ever represented a patent owner, weren’t you getting some cold-sweat flashbacks to some IPRs you’ve lost?)

This phrase “articulated reasoning with rational underpinning” could only be referring to a MINIMUM, not a standard of proof for deciding which side wins on the ultimate question of obviousness. And in the abstract, only two possible minima come to my mind. First, it could mean the minimum necessary presentation of an obviousness case to avoid the obviousness case getting rejected even before reaching the “merits”. And by the way, there are some PTAB decisions that seem to be doing something similar: where an IPR petition had a particularly vague, hamhanded, or cursory presentation of its obviousness grounds, the PTAB has sometimes said that the petition just simply failed to present a proper obviousness argument.

I tend to doubt that is what Justice Kennedy meant, though, because the context in KSR did not involve any contention that the obviousness argument in the case should or shouldn’t have been dismissed at the threshold like that. No, I think that all Justice Kennedy was referring to was the second of these two possible minima: the minimum necessary explanation that needs to be set forth by the tribunal that finds obviousness, to make its obviousness determination non-conclusory and capable of meaningful review by another, higher tribunal. Why? Because that’s literally the posture that was present in KSR, just like it’s present in every case the Supreme Court decides. Justice Kennedy’s opinion was simply remarking as to the sort of reasoning that the Supreme Court thought that the tribunal deciding the obviousness question (which, let’s remember, is a question of law, ostensibly reviewed de novo) was supposed to set forth so that a tribunal reviewing that trial tribunal would be sufficiently acquainted with the reasoning of the trial tribunal on this ultimate obviousness question.

That’s all! What it was intended to describe, in Judge Kennedy’s loose-knit not-very-thought-out way, was the minimum necessary reasoning that the tribunal finding obviousness had to set forth so its reasoning on the legal question of obviousness could be reviewed.

If you’re still not convinced, let’s take a close look at this language in KSR, with the language surrounding it, for a moment:

——————

‘Following these principles may be more difficult in other cases than it is here because the claimed subject matter may involve more than the simple substitution of one known element for another or the mere application of a known technique to a piece of prior art ready for the improvement. Often, it will be necessary for a court to look to interrelated teachings of multiple patents; the effects of demands known to the design community or present in the marketplace; and the background knowledge possessed by a person having ordinary skill in the art, all in order to determine whether there was an apparent reason to combine the known elements in the fashion claimed by the patent at issue. To facilitate review, this analysis should be made explicit. See In re Kahn, 441 F. 3d 977, 988 (CA Fed. 2006) (“[R]ejections on obviousness grounds cannot be sustained by mere conclusory statements; instead, there must be some articulated reasoning with some rational underpinning to support the legal conclusion of obviousness”). As our precedents make clear, however, the analysis need not seek out precise teachings directed to the specific subject matter of the challenged claim, for a court can take account of the inferences and creative steps that a person of ordinary skill in the art would employ.’

———————-

First of all, one can’t help but notice that this phrase isn’t even the Supreme Court’s own phrase at all: it’s the Federal Circuit’s phrase. The Supreme Court quoted it in a snippet of In re Khan–you know, one of the Federal Circuit’s infamous trio of decisions (Khan, DyStar, and Alzo, all three of which are quoted in KSR, though the latter two are quoted only sardonically) issued after KSR had cert granted and before it was decided, in which the Federal Circuit tried to influence the Supreme Court’s impending decision by issuing an opinion stuffed with hurriedly written dicta written to try to persuade the Justices that the Federal Circuit wasn’t really too pro-patent, wasn’t really letting more patents survive than the anti-patent Justices thought it should be, wasn’t really using a rigid test like the KSR briefing said, and shouldn’t be reversed or at least not reversed too hard. But leave that aside! Even if we assume arguendo that In re Kahn was not at all a weird, hurried, dicta-filled decision and was totally normal, this quoted language in Kahn is LITERALLY describing the minimum amount of explanation that an EXAMINER needs to present for his or her “rejection” of a claim to be “sustained” ON REVIEW.

Does the Supreme Court quote it out of context? Sure. But barely out of context. For the Supreme Court is quoting this phrase in a paragraph that is wholly devoted to the amount of explanation that a “court” must present for its finding of obviousness to be SUSTAINED on review in “more difficult” cases than KSR (where “[f]ollowing [obviousness] principles may be more difficult in other cases than it is here because the claimed subject matter may involve more than the simple substitution of one known element for another or the mere application of a known technique to a piece of prior art ready for the improvement”). Thus, the Supreme Court is not talking–at all– and the Federal Circuit was also not talking–at all–about the test for whether obviousness has been shown by a petitioner in IPR or an accused infringer or declaratory judgment plaintiff in district court. They were both talking about the minimum amount of explanation a tribunal finding obviousness needed to present in support of its obviousness determination in order for its determination to be sustained on review.

How do I know this has to be correct? Because the exact same thing is totally plausible if a court REJECTS an obviousness challenge. If a court (or the PTAB) rejects an obviousness challenge–which, I remind again, is a question of law, reviewable de novo–it is totally plausible that a short way to describe the minimum explanation necessary for the court to provide so that the nonobviousness determination is meaningfully reviewable on appeal is “articulated reasoning with rational underpinning.” That further confirms it, if further confirmation were needed.

Naturally, the language in KSR itself is arguably less crystal clear–it has to be unclear in some manner, because it’s been repeatedly misunderstood. But guess what? That happens all the dang time. Appellate courts say a lot of things, and they can’t all be gems, and the lower courts must stare at that imperfect expression of the higher court’s idea and consider its context and consider the posture and consider common sense and figure out what they think was meant by it. And one of the best ways to figure out what it DIDN’T mean is to show that if you interpret it to have such a meaning it would lead to absurdity.

Translation (if I may) for those not wanting to read through that:

The alleged standard is simply not determinative because both sides of the question can meet that standard at the same time.

Ah very interesting. I owe the Supreme Court an apology I guess.

I do not find KSR that confusing, at least as far as SCOTUS opinions go. It gets harder when you’re straining to square it with the “motivation to combine with reasonable expectation of success” matzo ball.

… when “you” are straining…?

Please explain.

“Could” is not good enough.

Please take a remedial patent class.

+1

Very good logic. If you doubt something you were taught in Sunday school, that means you need to go back to Sunday school.

Except Kyle, you are not at the position of “showing doubt,” as you are at the position of showing 1gn0rance.

Huge difference.

The “articulated reasoning with some rational underpinning” is that two techniques were disclosed in a prior art reference in the exact same field, and there’s no dispute a POSA *could* implement this technique in the way claimed.

That is not a reasoning to combine teachings. Moreover, “could” implement a technique is not the standard — it is “would.”

The claimed invention is not an unusual way of implementing the technique disclosed in Briggs. It’s implementing that technique in the exact way it was disclosed and is thus a “predictable use of prior art elements according to their established functions”.

That is your opinion.

As for paragraph 2). You did not refute that you made up a straw man argument.

The whole decision is premised on reversing a finding of fact, standard of review notwithstanding. And the FWD quoted that whole paragraph of Briggs on 19-20, so the Federal Circuit is on the hook, in theory, for having read that part.

No. It is not premised on reversing a finding of fact. Rather, it is premised on the expert not articulating a reasoning for the combination.

News flash: don’t hire hacks as “experts”. It’s nice to see a CAFC judge call out this person’s incompetence. I guess it’s “refreshing” to see this kind of hackery on the defense side instead of on the patentee/applicant’s side where it’s common as poppies in the spring (especially in the logic arts).

Read the second paragraph of page 22 of the Final Written Decision and ask yourself how that could have possibly been written by “persons of competent legal knowledge and scientific ability.”

Link or quote please.

“We disagree with Patent Owner’s arguments. Although the analysis

in the Petition could have been more robust, we continue to find that the

Petition provides a motivation to combine the disclosure of Keitler and

Briggs. The Petition provides the alternatives in Briggs, i.e., angular

direction and 3D coordinates, such that one of ordinary skill in the art would have understood them to be alternative formulations. Pet. 33–35. ‘A person of ordinary skill has good reason to pursue the known options within his or her technical grasp.’ KSR, 550 U.S. at 421. The two alternatives satisfy the criterion supplied in KSR of ‘a finite number of identified predictable solutions,’ such that it would have been obvious to try 3D coordinate process in the system disclosed in Keitler. That is what Petitioner is positing in its Petition. See Pet. 33–35. We find the support provided in the Petition to be sufficient, even absent additional support by Petitioner’s declarant.”

Just embarrassing.

But I give them credit for not using their banal autofill phrases “we are persuaded that…” and “we agree with petitioner that…”

Cue Random Examiner’s inevitable post on how if PHOSITA wanted to make toast in their car how it would be entirely predictable for PHOSITA to put a toaster in their car.

Assuming novelty, do you think putting a working toaster in a car is an invention?

But this toaster beeps when it’s time to feed your dog. And it’s in your car!

Do you think it’s possible to invent a car with a toaster in it? Put differently, if such an application crossed your desk and you found yourself having to combine 11 references to reject the claim, would you reject it?

A car with a toaster brings up a lot of utility and practical issues that could lead to an invention. How would you manage the crumbs or apply the butter and keep both hands on the wheel and eyes on the road?

“How would you manage the crumbs or apply the butter and keep both hands on the wheel and eyes on the road?”

Indeed. It is IMPOSSIBLE to manage those tasks, or so the art has led us all to believe.

Of course, we aren’t talking about a crumbless toaster with butter that requires no touching. We are talking about putting a toaster in a car. Oh and it beeps when it’s time to feed your dog.

Even the USPTO would not grant a patent for “an apparatus comprising a toaster disposed in a car”?

Even the USPTO would not grant a patent for “an apparatus comprising a toaster disposed in a car”.

What’s the most number of references in combination that Ben has used to reject a claim?

13. For a piece of candy.

Cue Random Examiner’s inevitable post on how if PHOSITA wanted to make toast in their car how it would be entirely predictable for PHOSITA to put a toaster in their car.

Glad to see the talk is sinking in. But it’s not predictable because someone wants to make toast in their car. It’s predictable because the art knows the toaster doesn’t care whether its environment has wheels when it is toasting bread.

Do you think it’s possible to invent a car with a toaster in it?

Sure, it’s just not inventive BECAUSE of the toaster.

Put differently, if such an application crossed your desk and you found yourself having to combine 11 references to reject the claim, would you reject it?

The number of references is not legally relevant. I have no doubt that if I described my living room, comprising dozens of different commercially available items, it would take dozens of references to teach the system claim. My living room is not inventive.

Assuming its a common car and a common toaster, I would reject it even if it took a hundred references. Hyper-specifically parroting back what the art already knows is not a nonobvious claim.

Even the USPTO would not grant a patent for “an apparatus comprising a toaster disposed in a car”?

Ehhhh…

“It’s predictable because the art knows the toaster doesn’t care whether its environment has wheels when it is toasting bread.”

Does it?

“Hyper-specifically parroting back what the art already knows is not a nonobvious claim.”

Except it very well could be.

Your error is what I post at 2.2.

Does it?

If we’re in obviousness because the prior art has a toaster in the kitchen rather than a car, and we follow the rule that applications are presumed to be enabled, we know that toasting occurs irrespective of wheels. However, you are correct that if it were true that wheels made an unexpected difference in toasting outcome, then certainly the applicant could provide evidence of unexpected results and prevail on secondary considerations. “Bread toasts differently based upon velocity of the toaster” is the kind of information disclosure that patent law protects, unlike “Previously nobody thought a toaster in a car was commercially valuable, so I deserve a patent for an electrically obvious marriage of elements because I have a nonobvious commercial motivation.”

I have invented a small practical nuclear fusion reactor that fits in and powers my car.

And it makes buttered toast. Jelly is optional.

And it tells me when it’s time to feed my cat.

In the EPO, the number of references is very relevant. They somehow manage to maintain a seemingly well-functioning patent system while rarely resorting to more than three references in an inventive step objection.

But if you described your living room in a claim that required 11+ references to find all the elements, the more important question is not whether it is obvious, but why would anyone do that in the first place? Patent law at the end of the day is purely commercial law, not some kind of natural law or right. It was created by entirely by man to regulate and, in theory, promote commercial activity. Yet, so many of the hypothetical inventions and claims people bring up here to make grand points have absolutely no commercial point at all – no value to anyone. No one is ever going to litigate a patent on your living room.

But what about a machine that actually produces some useful result? Say it takes five references to find all the elements of the claim (not an uncommon USPTO rejection). The fact that it took five references means that it is per se novel – no one has ever created that machine before; it did not exist before the inventor created it. Now the claim to that machine is in a post grant review or litigation. Why? Because it is commercially valuable enough for others to make it and spend potentially millions of dollars in legal fees fighting for the right to make it, even though it never existed before throughout all time and no one else tried to do the same thing until after the inventor started to make money with it.

I don’t really have an ultimate answer to what is the right test for obviousness; it is a difficult question. But no one is ever going to get to the right answer debating bizarre hypotheticals well outside of the only applicable context for the existence of patent law.

Go ahead and issue, or reject the patent on your living room. No one will ever care either way and the decision either way offers absolutely no useful insight into how to consider the patent on the novel machine that created a new, valuable business that justifies millions of dollars spent both to copy into it and to keep out the copyists.

Please take care NOT to confuse non-US patent law (and reasoning) with what you may be familiar with from the EPO.

“Patent law at the end of the day is purely commercial law, not some kind of natural law or right.”

This is not true for the US Sovereign.

This is itself a very confusing comment.

1) There was no confusion between the two systems; just a suggestion that one system may have a better approach than another system to an issue that is common to both. Are you saying that one patent law system may not be informed by may work better in another?

2) What is “the US Sovereign” ? – did you mean system?

The US patent law system is expressly based on the US constitution – art. I, sect. 8, cl. 8 to be specific. So how is that not true?

I’ve seen scholarship that suggests a natural law basis for patent law, citing back to sources like Jeremy Bentham, John Locke and even Thomas Aquinas, but that always seems more like argument for the purpose getting law review articles published rather than to suggest an actual “new and useful improvement” to patent law itself.

It is only confusing because you lack understanding of the principles of US patent law.

We do not want your system.

Better informed would be YOU making a comment that actually recognizes (and respects) our system and then suggesting why your desire would be better.

You clearly did not do that here.

Further, if you have to ask me, then you clearly do not know – which proves my point.

Our system is built on the foundation from Locke – turning MAN’s inchoate right into a bundle of actual legal rights with a Quid Pro Quo.

Unlike your sovereign, whose Quid Pro Quo is publish for mere chance at patent, our foundation runs deeper.

“No one is ever going to litigate a patent on your living room.”

Oh but wait! The claim can be construed so it also reads on certain rooms in apartments, nursing homes, hospitals and hotels. I can’t be 100% sure that every room is infringing, of course. That will be resolved after discovery.

RG: “My living room is not inventive.”

The real problem is that our weak patent doesn’t encourage you to protect your inventive living room. This is why progress in American living rooms has been so slow.

wow wrt the expert.

The declarant’s poor showing seems to me to be poor preparation by the attorneys.

But I do like this case.

“Belden Inc. v. Berk-Tek LLC, 805 F.3d 1064, 1073 (Fed. Cir. 2015). At oral arguments, Judge Hughes noted that indeed it does seem quite technologically simple to combine the references together, but repeatedly asked about the motivation — why would someone be motivated to do so:

KSR does allow a somewhat relaxed look at obviousness. But the references have to show not just how you would combine them, but why you could combine them. And where in any of this record is that why answered?

Oral Args. at 15:14. Chief Judge Moore agreed:

You have to agree that just because a bunch of things are known in the industry [does not make the combination obvious], that would turn obviousness on its head. Hindsight would run rampant if just the mere fact of things being known was sufficient to then piece them together without that ‘why.’”

Many examiners leave out the “why.” Or say, “to improve ______.”

This was an IPR lost [not a remand] for the all too common failure to provide an expert declaration in the case in chief [filed with the IPR petition, not later on] as to why the combining of the petitioner’s applied references was motivated and thus obvious to a POSITA.

BTW, readers of this Fed. Cir. decision might suspect that, this had been an application examiner prima facie obviousness claim rejection on the same prior art, rather than an IPR claim rejection, that it might have stuck? I.e., the opposite of what one would normally presume?

“BTW, readers of this Fed. Cir. decision might suspect that, this had been an application examiner prima facie obviousness claim rejection on the same prior art, rather than an IPR claim rejection, that it might have stuck? I.e., the opposite of what one would normally presume?”

Depending upon the applicant, yes. They know that most applicants are not going to have the stamina (money) to appeal to the Federal Circuit, and that is usually where one would have to go.

Of note, the “why” is NOT A why of benefit of an item, but a “why” to combine the items.

Any benefits of an item singularly is simply NOT the benefit of a combination.

103 Art is not piecemeal 102 Art.

Exactly.

Of note, the “why” is NOT A why of benefit of an item, but a “why” to combine the items.

It’s not a why at all, which I assume you recognize by putting why in quotations. Again, my living room is not a nonobvious system simply because I happen to have some inarticulable motivation toward some particular grouping of commercially available prior art. It’s sufficient to say that all of the parts of my living room system were previously known and they are all behaving in their expected way when placed together as one would have expected when they were purchased separately.

Explaining “why” certain things exist can certainly improve the rationale – I suspect the reason “why” there’s a tv stand in the living room may be motivated by the existence of the tv in the living room – but if you sold the tv the system would not suddenly become nonobvious because the tv stand is claimed but has no logical basis for being there. Indeed that would make a narrower claim (living room with tv and tv stand) obvious while the broader claim (living room with tv stand) is nonobvious, which cannot be.