by Dennis Crouch

Western Digital Techs., Inc. v. Viasat, Inc., No. 22-CV-04376-HSG, 2023 WL 7739816 (N.D. Cal. Nov. 15, 2023) Docket No. 4_22-cv-04376

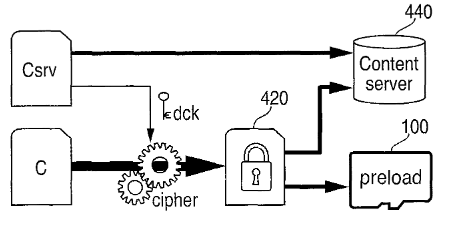

Western Digital sued Viasat for infringing claims from several patents, including US8,504,834, which covers “media streaming systems and software.” In a recent decision, Judge Haywood (N.D.Cal.) granted a motion to dismiss — finding the claims of the ‘834 patent directed to ineligible subject matter. The background section of the patent explains explains that prior art systems decrypted locally stored content using a decryption key obtained from a digital rights management (DRM) server. This had drawbacks related to efficiency and cost. The patent describes an improved system where the decryption key is derived from a stream of data received over a network, rather than needing to contact a DRM server.

Claim 14, treated by the court as representative, recites:

A method for activation of local content, the method comprising:

performing the following in a host device in communication with a storage device storing encrypted content:

receiving a stream of data from a network;

deriving a key from the received stream of data; and

decrypting the encrypted content using the key derived from the received stream of data.

The claim covers a method for decrypting locally stored encrypted content. A host device receives a stream of data over a network, derives an encryption key from that stream, and uses that derived key to decrypt encrypted content stored on a connected storage device.

Alice Step One – Is the Claim Directed to an Abstract Idea?

At Alice step one, the court asks whether the claim is “directed to” a patent ineligible abstract idea. Here, the court found claim 14 is directed to the abstract idea of “delivering and deriving a decryption key from a stream of data.” The court provided several bases for deriving this idea as gist of the claim and for concluding that it constitutes an abstract idea.

First, the court analyzed the focus of the claimed advance over prior art systems as described in the patent background and specification. The court found the focus was on using a stream of data to deliver and derive a decryption key, rather than contacting a DRM server.

The court then noted that the claims are functional in nature — claiming the result itself. On this point, the court found that claim 14 does not recite any practical method of implementation, but rather uses only generic computer components like a “host device” and “network” along with conventional processes like “receiving,” “deriving,” and “decrypting” to achieve the result. This demonstrated the claim was drafted in a result-oriented or functional manner focused on the principle itself.

The court also found that the key steps of claim 14 could be performed by a human mind or with pen and paper by deriving a decryption key from a received communication and using it to decrypt content. This indicated abstraction under Federal Circuit precedent.

Finally, the court analogized the claim to those found abstract in several other cases, where claims merely collected, organized, transmitted data without a specific new process for doing so, including Electric Power Group, LLC v. Alstom S.A., 830 F.3d 1350 (Fed. Cir. 2016) (collection, analysis, and display of data are abstract), and Two-Way Media Ltd. v. Comcast Cable Commc’ns, LLC, 874 F.3d 1329 (Fed. Cir. 2017) (broad functional steps that lacked technical details were abstract).

Alice Step Two – Does the Claim Recite an Inventive Concept beyond the Abstract Idea itself?

At step two of Alice, the court searches for an inventive concept to ensure the claim amounts to significantly more than the abstract idea. Here, the court found no inventive concept in claim 14, when considered either element-by-element or as an ordered combination.

The court found that the claim elements recite only generic computer components like a “host device” performing conventional computer functions like “receiving” and “deriving.” Plaintiffs apparently did not dispute this.

For the ordered combination, Plaintiffs argued that using streaming data to provide decryption keys in the claimed manner was unconventional and advantageous over prior systems. But the court rejected this, finding that any such unconventional use or improvement described in the specification was untethered from the broad claim language. The court held that even assuming the specification discloses specific steps rendering use of streams unconventional, those details are missing from claim 14.

Conclusion

Because this was at the motion to dismiss stage, the Court permitted Plaintiffs leave to amend their infringement allegations related — perhaps to include factual allegations that show eligibility. However, the patentee subsequently provided the court with notice that it will not be filing an amended complaint.

While Plaintiffs respectfully disagree with the Court’s determination under 35 U.S.C. § 101 for all of the reasons set forth in its briefing on the issue (see, e.g., Dkt. No. 53), Plaintiffs are not filing an amended complaint and instead reserve the right to appeal the Court’s decision when final judgment is entered in this case.

P’s Response to the Court’s Order. The case is ongoing with two additional Western Digital patents — each which contain claims with more technological detail imbedded into the claims. The outcome here recognizes that patentees are finding ways to overcome the eligibility issues, both at the PTO and in court, but there are still lots of traps. Though workarounds now often exist, Alice/Mayo still present ample opportunities to find claims abstract – particularly for computer-implemented inventions. The path forward for Plaintiffs remains challenging despite their arguments on appealability.

Uh yea but the section of the statute is entitled “Inventions Patentable” and goes on to list kinds of things that could be….you know….inventions patentable.

Just as the words in claims are construed as a matter of law, so should be the useful result of a method patent.

When judges find (or not find) the AbSTraCT IdEa that’s in effect what they are doing; that event should be more like a Markman proceeding, with technical explanation and argument.

As to the metronomic mor onacy of “traffic lights”, the light itself is a patentable article. A new and better way of displaying a red light should also certainly be patent eligible.

A method whereby a driver stops when they see a red light should not be patent eligible.

What is the difference between a traffic light and knowing to stop at a traffic light? All the difference in the world.

The height of your peak of Mount

S

t

u

p

I

d

continues to befuddle you.

Please have your patent attorney explain to you the patent concept of utility.

A claim to a thing with blinking lights – without more does NOT have the necessary patent utility of a traffic light.

The utility comes from — and is not separable from — its use and that “information for human consumption.”

It is just a bad look for you to denigrate with names that describe you.

Uh yea but the section of the statute is entitled “Inventions Patentable” and goes on to list kinds of things that could be….you know….inventions patentable.

What is the remedy prescribed by the statute for not meeting 35 USC 101? I’ll give you a hint. There is none. Also, the vast majority patents invalidated under the judicially-created exceptions to 35 USC, do fall within what is described in 35 USC 101. 35 USC 102 talks about how a “person shall be entitled to a patent unless …”. 35 USC 282(b) talks about defenses to patents. 102 and 103 are described as conditions for patentability. 101 is not.

Just as the words in claims are construed as a matter of law, so should be the useful result of a method patent.

The useful result of a method patent should be construed? Where does that come from? That has no basis in statutory or case law.

When judges find (or not find) the AbSTraCT IdEa that’s in effect what they are doing

The Supreme Court already admitted that there is almost always an abstract idea to be found. So what of it?

A method whereby a driver stops when they see a red light should not be patent eligible.

And if an autonomous vehicle does that using image recognition (or perhaps communicating with a traffic light using wifi or some other type of communication channel), is that patent eligible? Is it patent eligible when it is not an autonomous vehicle, and the vehicle alerts a ‘distracted’ driver of a detected road condition ahead (as opposed to automatically applying the breaks)?

What is the difference between a traffic light and knowing to stop at a traffic light? All the difference in the world.

Compared to the technology of the traffic light itself, the technology used to know when to stop at a traffic light could be far more sophisticated.

Humans are capable of doing lots of different things. Should replicating those things with machines not be patentable on that basis?

So 101 is pure surplus; an ornamental preamble that does zero work.

OK then.

Compared to the technology of the traffic light itself, the technology used to know when to stop at a traffic light could be far more sophisticated .

Yes, that “technology” is a human mind, and it’s very much more sophisticated than a traffic light, and it should be beyond the reach of the patent system.

Humans are capable of doing lots of different things. Should replicating those things with machines not be patentable on that basis?

Exactly the opposite.

The useful result of a method patent should be construed? Where does that come from? That has no basis in statutory or case law

It comes from the free-for-all we have now in every district court, just like we did before Markman with claim construction. A method without a useful result is not a method.

So 101 is pure surplus; an ornamental preamble that does zero work.

It is mostly a statement of purpose. To the extent that it is a statement of condition, it opens a very wide door through which to walk.

Yes, that “technology” is a human mind, and it’s very much more sophisticated than a traffic light, and it should be beyond the reach of the patent system.

That technology is not necessarily the human mind. Along those same lines, the human mind is not technology. Also, doesn’t the “useful clue” provided by the machine-or-transformation test address your issue.

Exactly the opposite.

The opposite of what? If this was a claim, it would deserve a 112(b) rejection for being indefinite.

It comes from the free-for-all we have now in every district court, just like we did before Markman with claim construction. A method without a useful result is not a method.

First, who is claiming methods that don’t have utility? Second, the claims aren’t required to disclose utility. Third, the utility requirement is both separate from the judicial exceptions and extremely easy to meet.

Wt,

You are trying to have a conversation with someone who has absolutely refused to understand the patent sense of utility.

To the extent that it is a statement of condition

mmmmmm. Once it’s a state of condition, there are facts which don’t meet the condition. You can call those facts a defense or not a defense, but the result is the same for a litigant.

A method without a

usefulresult is not a methodThere, fixed it. The point is the same with zero discussion of utility. the result of a method IS the invention, and inventions should be construed before they are fully litigated.

As of now, each district court constructs the invention as they see fit whenever a 101 challenge is raised. The procedure ought to be formalized.

“the result of a method IS the invention”

No.

Clearly not, as there is almost always multiple ways to arrive at pretty much any given result.

Your pet pony just does not ride here.

No result, no method

LOL – move the goal posts back.

Or is your next post an assertion that the result is the invention?

Better yet, address the last point put to you (after consulting with your patent attorney, of course): link to patentlyo.com

mmmmmm. Once it’s a state of condition, there are facts which don’t meet the condition. You can call those facts a defense or not a defense, but the result is the same for a litigant.

Defenses are described in 35 USC 282(b) – they don’t mention 101. Also, while 102 and 103 are described as being conditions for patentability, 101 is not similarly described.

the result of a method IS the invention

Absolutely wrong. Digging a hole with a shovel produces the same result (i.e., the hole) as digging the hole with an auger or digging the hole with dynamite. These are not the same invention. To the extent that any are patentable, patentability (or inventiveness) lies in the different steps — not the same result.

No hole, no method

Talk to your patent attorney, marty.

You are embarrassing yourself.

Again (still!)

Please Pardon Potential re(P)eat (filter yet again)

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

December 16, 2023 at 7:45 am

The topic – yet again – for you to discuss with your patent attorney is the concept of utility in the patent law sense.

Your “No hole, no method” quip properly translates to

“No [recognized in the human mind of utility of a] hole, no [patent utility for the claimed] method.”

This is eminently true as well for the other statutory categories.

Let’s take that simple example of the traffic light.

“No [recognized in the human mind of utility of a] traffic light, no [patent utility for the claimed] manufacture.”

Without the recognition in the human mind, a MERE manufacture of a metal object with colored blinking/alternating lights does NOT have utility in the patent sense.

I have also debunked your view with another example of:

“a sharp edge.”

Your example fell short, as you did not grasp the fact that you attempted to not recognize that the human mind is needed to make “a sharp edge” into a a cutting utensil.

Part of me (pre-law) real world experiences include work on a factory floor that involved sheet metal.

Sharp edges in that context was very b@d.

The patent law concept you desperately need to grasp is that ALL utility in the patent sense is realized ONLY AS being utility IN the human mind.

Shall we send out a search party for marty?

As usual, short work in my scheme.

Is it a method? Yes

Is the useful result of the method some species of information? Yes

Does the utility of the information arise in a human mind? No, computing systems use the intra stream key information to gain efficiency.

Eligible.

Is including a key in a stream obvious to PHOSITA? Don’t know. Seems likely.

Do the claims teach PHOSITA to place a key in a stream? Don’t know.

Seems unlikely, but also seems unlikely that PHOSITA would need such teaching once motivated to place a key in a stream.

Should there be a early-stage procedural mechanism other than a 12(b)6 / 101 on these questions? |

“… in my scheme”

Traffic light.

Full stop [pun intended]

Marty, this is a classic example of a claim where the application of your “eligibility determination logic” reveals the uselessness of that methodology.

This claim is functional j – nk. There is nothing there except “use an encryption key derived from a stream of data.” That’s it. That’s not an invention. It’s nothing. Reciting “on a computer” changes nothing and it’s a sign of absolute failure of your methodology that such recitation is considered to change everything.

^^* Wolfgang Pauli’s “not even wrong,” and you lecturing marty is Delish irony.

I don’t see your point. Why does a non-invention default to a matter of ineligible subject matter?

When claims fail for lack of written description, there is a non-invention, but we don’t say it was for lack of eligibility.

When claims fail for anticipation there is a non-invention, but we don’t say it was for lack of eligibility.

When claims fail for obviousness, there is a non-invention, but we don’t say it was for lack of eligibility.

So when a claim fails because it’s functional gar*bage, why should we say it’s for lack of eligibility?

Where do I say if it’s done “on a computer” it’s eligible where if it weren’t done on a computer, it would not be? There are tons of purported “inventions” that produce information meaningful to persons. They shouldn’t be eligible.

The structure of the patent act seems to separate eligibility from patentability – I am hardly the only one to notice that- so why are functional claims an eligibility issue and not a patentability issue?

“There are tons of purported “inventions” that produce information meaningful to persons.”

Like traffic lights.

Oopsie.

If we had a simple claim to a computer like “a computer comprising a memory and a processor,” that claim would be eligible but lack novelty (i.e., its just a list of hardware components). Yet a more narrow claim would not be eligible, like “a computer comprising a memory and a processor configured to output advertisement recommendations.” How can a broader came be patent eligible, but not a narrower more limited version? The law is broken.

There’s nothing “broken” about a system that keeps j-nk claims out for predictable reasons of the sort you just described. Moreover, the point in both instances is that there is no patentable invention. So what is your problem again?

Ends do not justify the Means.

Your comment of “Moreover” absolutely misses the point.

But you already knew that, eh Malcolm?

The structure of the patent act seems to separate eligibility from patentability – I am hardly the only one to notice that- so why are functional claims an eligibility issue and not a patentability issue?

The patent act does not separate eligibility from patentability. Eligibility is a construct of the courts.

If you look at 35 USC 282(b), which involves defenses, ‘not eligible’ is not a defense. Defenses are noninfringement (b)(1); invalidity resulting from a condition for patentability (b)(2); failure to comply with section 112 (b)(3)(A), or 251 (b)(3)(B); or “Any other fact or act made a defense by this title.”

While I’m thinking of it, for those of us who believe the Supreme Court has overstepped their bounds, we should stop tying the “exceptions” to “patent eligibility” and/or 35 USC 101. To do so, in essence, gives credence to the notion that these exceptions are somehow derived from the text of the statutes.

Rather, we should be calling these exceptions something akin to “court-made exceptions to statutory law.”

So when a claim fails because it’s functional gar*bage, why should we say it’s for lack of eligibility?

What is the meaningful difference between functional claim language and language found in a method claim?

“ So when a claim fails because it’s functional gar*bage, why should we say it’s for lack of eligibility?”

When the only novel element in a claim is a function divorced from any novel structure, what’s being claimed is an abstraction, a concept, or a dream, none of which are statutory subject matter.

Moreover, there’s nothing wrong about a claim being both ineligible and also failing under one or more of the other statutory categories which all have similar goals in mind: preventing the granting of (or promoting the elimination of) patents to alleged “inventions” that are not patent-worthy (and never were) because they are half-baked j-nk.

Element?

Element in a claim?

Do you hear yourself?

Upon reading the headline (and caveat that I have not yet waded further in), I am reminded of the author’s own coined phrase that deals with claim elements sounding in function:

“Vast Middle Ground.”

I have noticed that since that phrase was first uttered – and its implications made explicit by yours truly, that the use of the phrase has disappeared from the narrative.

One is left wondering why in the wonder this would be so.

Drafting [] Claims Still Risky Post-Alice

Fixed it for you.

But the court rejected this, finding that any such unconventional use or improvement described in the specification was untethered from the broad claim language.

And the dependent claims appear to recite specifics. But let me guess — the Court ignored those.

+1

What are these oh-so-fabulous “specifics”?

The ‘834 patent was filed in Dec. 2011, way before the SC decided Alice (2014). No one back then thought about adding “something significantly more” than an “abstract idea”, because those didn’t exist.

And this is after KSR, so everyone was terrified of discussing problems with the prior art. The background is only two paragraphs long, and I don’t see additional description of the problems.

“ No one back then thought about adding “something significantly more” than an “abstract idea”,”

Translation: “My head was buried deep in my behind until Alice was by the Supreme Court. Also I prosecute like a frightened low-IQ rabbit so have pity on me.”

LOL

> delivering and deriving a decryption key from a stream of data

Tbh, deriving a decryption key from the encrypted content itself sounds kinda wild. On one hand, I guess code breakers do that…on the other hand, the fact one could do so meant the encryption scheme was useless/harmful

Where did you see that? The stream of data and encrypted content are separate elements.

On its face, the claim is agnostic as to whether the “content” of the encrypted data is necessarily different from the “content” of the streamed data comprising the key. But I agree that coverage of an embodiment where the content is identical seems to create even more problems for this highly problematic claim.

I think it’s pretty clear on the face of the claim that the encrypted content, which is previously stored on a storage device that the host communicates with, is different from the data stream the host then receives from the network. Not that it really impacts anything with respect to the key issues in this case.

The biggest problem is that this claim reads on decrypting content using a key. No way that’s patentable or subject matter eligible.

… or subject matter eligible…

Oh my sweet stars and garters

I agree with everything you wrote, kotodama. There is data that is stored, and (separately) there is data being streamed. What I was trying to say is that the claim doesn’t require the *content* (i.e., the “meaning” or “purpose”) of the two collections of bits (i.e., the stored data and the streamed data) to be different.

And again: I agree with you that this has little or no bearing on the failure of this claim. Certainly doesn’t help the claim!

That’s very unusual – dare I say patentable? – to derive a key from a received stream of data. (Don’t have time to see how they do that.)

Wouldn’t receiving a key using TCP/IP constitute deriving a key from a received stream of data? There may be novel ways of deriving a key from a received stream of data, but the representative claim is not limited to a particular method.

I’m sure there is a very special definition of “deriving” in the specification with all kinds of novel “structure.”

Not.

Your ‘rebuttal’ appears to conflate a comment on novelty with the other legal point of eligibility.

As you are “quick” to point out that claims MAY

F

A

I

L

for more than one reason, the proper rejoinder to you is to NOT conflate those possible more than one reasons.

NO ONE has argued that a claim lacking novelty impinges on whether or not the claim thus necessarily lacks eligibility.

Except for you.

It’s how I’d interpret “derive.” In part b/c public-key encryption systems have pretty much always encrypted the actual content with a one-time key (which, in turn, is encrypted using the more-expensive PKI algorithm).

:fake edit: OK, maybe I’m wrong here…. the rest of the claims sound like they are just unlocking content already on the device:

7. The host device of claim 1, wherein the encrypted content is pre-loaded on to the storage device.

If so, I’m less impressed.

Comments are closed.