The Debacle Inside Rikers, And Why Shutting It Down Isn’t Enough

The real problem that must be faced is the over-incarceration of mostly people of color, with little emphasis on rehabilitation once they’re 'warehoused.'

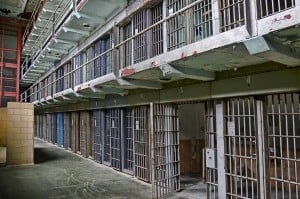

(Photo by Bob Jagendorf/Getty)

Last week, legislators visiting the prisons on Rikers Island called the situation there “a humanitarian disaster.” It’s also a case study of how not to run a prison.

Most of my clients are “housed” at Rikers Island. Housed is the term used, but it’s more like “warehoused.” No clean running water, restricted access to family, little if no time outside the cell, no toilet paper or blankets, showers where water dribbles rather than flows, and worst of all, not enough guards to protect either themselves or the inmates they patrol.

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Over the years, I’ve gotten used to the dehumanizing nomenclature of prisons. The “feeding,” the “count” — the daily process of making sure everyone’s accounted for — and “the bodies,” as in “we don’t have the body yet” when awaiting a client in court.

But I’ve never encountered the level of chaos as now seen at Rikers Island. Even my clients who never bother me — the ones who are easy to work with and realistic — are worried. Will they be hurt or even die while waiting for their cases to get to trial?

Rikers sits on a small spit of land across from LaGuardia Airport. It’s the base for 10 separate prison facilities that have become the focus of media attention.

Correction officers are calling in sick in numbers never heard of. Not because they’re actually sick, says their new commissioner, Vincent Schiraldi, but because they don’t want to be at work. It doesn’t help that they have unlimited paid sick leave and very little oversight.

Sponsored

Is The Future Of Law Distributed? Lessons From The Tech Adoption Curve

Generative AI In Legal Work — What’s Fact And What’s Fiction?

The Business Case For AI At Your Law Firm

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

Next there’s COVID-19. Who wants to go to work when the overcrowding in jail makes it easy for contagion to spread?

The fewer the guards, the more dysfunctional the jails become, and the more dangerous for inmates and guards alike. Without guards to keep order, violent inmates prey on the less strong. Carrying a make-shift knife has become a necessity — for protection.

It’s come to a point where inmates are escorting each other to video appearances in court or with their lawyers. Violence is rampant, as well as suicide. The sick are not seeing doctors, and whole wings normally staffed by three or four correction officers are now staffed by one, if that.

No one seems to be in control.

A client of mine with a blood-clotting problem was worried that if he were to be attacked, he’d “bleed out” before a guard even noticed or was able to get him medical attention.

Sponsored

Navigating Financial Success by Avoiding Common Pitfalls and Maximizing Firm Performance

Legal AI: 3 Steps Law Firms Should Take Now

The hue and cry to “shut down Rikers” is too little and comes too late. Such plans have been bandied about for years on a hope other facilities would be built where the Rikers inmates could go. Meanwhile, money for basic maintenance at Rikers stopped coming. Buildings fell into disrepair. Heat is scare in the winter, and air conditioning uncertain in summer.

The idea of closing Rikers wasn’t to “decarcerate” the people there charged with violent crimes (the majority of those there now), but to shift them to new digs — more updated, more “humane.” That hasn’t happened.

The real problem that must be faced, however, is the over-incarceration of mostly people of color, with little emphasis on rehabilitation once they’re warehoused. The Rikers prison problem stems from society’s disdain toward people accused of crimes: Who cares how they’re treated? They did something wrong; let them rot.

First, this attitude ignores a keystone of our criminal justice system — people accused of crimes are innocent until proven guilty.

Next, incarcerating people for what has now been years (because of COVID-19) while awaiting trial, is unnecessary and unfair. Bail should be set even on those accused of violent crimes but that bail should be commensurate with their ability to pay.

New York is regressive in its approach to bail, in spite of bail changes made last year that made things slightly better for people accused of nonviolence offenses.

Judges have wide latitude to set whatever bail they think is appropriate. But often their gauge is synced to what a middle-class person with a job, savings, and a family with income can afford, not what 90 percent of the people in jail, mostly indigent, can make.

For a poor person, $1,000 is a huge amount of money that will guarantee he comes back to court even on a robbery charge. While, for someone like Harvey Weinstein, $1 million may not be enough.

During COVID-19, New York implemented an ankle bracelet program to encourage the release of inmates by providing a backup measure (in addition to bail) to ensure a defendant wouldn’t flee. The monitors track the wearer’s location at any given moment. If removed without permission, a signal is sent immediately to law enforcement. Yet prosecutors put down their use as too easy to cut off, and it’s a rare judge who has the courage to go against what a prosecutor requests. Since the program started, fewer than 100 inmates have been approved.

If bail was set more reasonably and in keeping with the financial capacity of the accused, and if the ankle bracelet program were more widely accepted by judges, fewer people would be in jail awaiting trial. And the situation that’s been allowed to fester at Rikers could be avoided.

Toni Messina has tried over 100 cases and has been practicing criminal law and immigration since 1990. You can follow her on Twitter: @tonitamess.